Shownotes

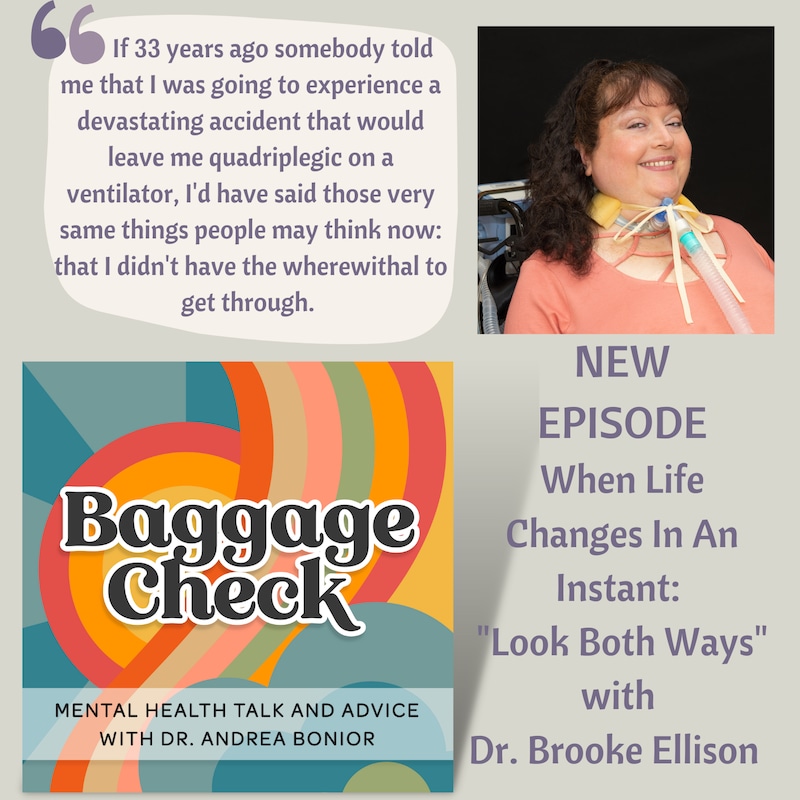

Today we're talking with Dr. Brooke Ellison, associate professor at Stony Brook University, author of Look Both Ways, and subject of the Christopher Reeve- directed documentary, The Brooke Ellison Story.

When Brooke was just 11 years old, walking home from her first day of junior high school, she was hit by a car-- and left with quadriplegia. In a raw, no-holds-barred conversation, we talk not only about that fateful day and the way it changed her life forever, but what it can teach us all about resilience, struggle, perseverance, and hope. Completely honest, full of insight, and often funny, today's discussion is not one to miss.

Order "Look Both Ways" wherever books are sold, and connect with Dr. Ellison and learn more about her work here.

Follow Baggage Check on Instagram @baggagecheckpodcast and get sneak peeks of upcoming episodes, give your take on guests and show topics, gawk at the very good boy Buster the Dog, and send us your questions!

Here's more on Dr. Andrea Bonior and her book Detox Your Thoughts.

Here's more on this podcast, which somehow you already found (thank you!)

Credits: Beautiful cover art by Danielle Merity, exquisitely lounge-y original music by Jordan Cooper

Transcripts

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Sometimes life can change permanently and irrevocably in a microsecond. Imagine that you're eleven years old, walking home from school with a group of friends, and you are hit by a car. You sustain injuries to every part of your body, and it's deemed likely that you won't survive. You, when you come out of it, you are paralyzed from the neck down and fully dependent on a ventilator. Do you imagine that you have what it takes to start moving forward and building your life again? Our guest today is Dr. Brooke Ellison, associate professor of health policy and medical ethics at Stony Brook University and the author of um Look Both Ways and Miracles Happen, which was adapted into the Brooke Ellison story directed by Christopher Reeve. Brooke lived this path, and her story applies to all of us. If you've ever been curious about resilience, trauma, and growth after life is turned upside down, you'll want to listen to today's Baggage Check. Welcome. I'm Dr. Andrea Bonior, and this is Baggage check, mental health talk and advice. Thank you for being here today. I'm very glad that you are. I must remind you that Baggage Check is not a show about luggage or travel incidentally. It is also not a show about why nobody seems to cover textbooks with brown grocery bags anymore. Okay, onto the show today, I have got a great conversation for you. I have as a guest Dr. Brooke Ellison, who serves on the faculty of Stony Brook University, who graduated magna cum laude from Harvard University with a degree in Cognitive Neuroscience. She got her master's in public policy from the Harvard Kennedy School of Government and her PH D in sociology from Stony Brook University, where she teaches today. Her, uh, most recent book, Look Both Ways, details a defining moment of her life, which is the day when she was eleven years old and was hit by a car. And her path since Brooke became a quadriplegic. Her story resonated with me so much, and I don't even know where to begin in telling you the things we covered, because I know it's going to resonate with you as well. We talked about resilience and social connection and humanity, and what it means to just completely start from scratch. How easy it is to take things for granted. How disability, in some ways, is a construct that represents obstacles for all of us to connect with her. Check out her website at, uh, Brooke ellison.com that's Brooke with an E, and then ellison.com and Look Both Ways is available wherever you like to buy your books. Let's get to it. I learned so much from this conversation. Welcome Dr. Ellison to baggage check. I am so glad to have you on the show today.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: Thank you. The pleasure is absolutely all mine. Thank you.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: So I've been able to take a look at your book, Look Both Ways, and there are so many aspects of it that I want to talk about today. But first, and I know this is the second time that you've written something so personal. I was curious how it feels to have your life out there on the written page, to have people reading it and really understanding the inner workings of you and your emotional landscape in a way that's quite personal. What has that been like?

me of my accident way back in:Dr. Andrea Bonior: Do you want to talk to literal.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: Super crush on him when I was, when I was a kid? So he wasn't going to say no to that. Um, and then he asked, can I tell your story in the form of a movie? Um, and of course, at the first it just kind of knocked you over a bit. And then I had to think, wait a second. That's not just a question for me to answer. I have to talk to my family about this because it's going to be their lives on display just as much as my own. So we had a familiar conversation about it and talked about, um, where do the benefits lie? Where are some things that we need to think about, um, a little bit more cautiously? And my family came to the conclusion that we have had a series of experiences that are valuable to people. People who are undergoing levels of difficulty or have experienced hardship that can feel very isolating and feel like you've been distanced from the world. So that was kind of the premise that we went ahead on and thought, this is something that could be quite impactful. And that turned out to be the case whenever. The Progellos Story, the film that was based on my initial book, it's shown anywhere. It's shown all around the world. So I've heard from you, Ball, africa and Australia, just literally all over the world. People share their lives with me. They tell me about their experiences and different struggles that they've had and how they feel like parts of our story gives them, um, either a sense of, um, purpose or a newer perspective on their lives. And I think that's been quite powerful for me. So when it came time, and in the years since then, I do a lot of talking about my life. Um, I give speeches and presentations and a lot of writing, introspective writing. So when it came time that I decided to write look both ways, which was just, um, several years ago, actually, right after my 40th birthday. Um, this was at a time in my life when I was experiencing a lot of health challenges. I had become very sick with a pressure wound that needed to be treated for quite some time. And my life was in question, right? My ability to survive what I was experiencing was in question. I said I had known that for a while and I wanted to write another book after my first book was published. And then this opportunity came around and I said, you need to write from the heart. You've had important experiences that people can learn something from. And it's not just those experiences, but the lessons that have been borne out of those experiences. And you need to be thoughtful about this. So I kind of squirreled myself away, locked myself away in my bedroom and that summer just wrote and wrote and wrote and forced myself to be as self probing as I could possibly be and talk about things that I did that I was kind of afraid and felt very vulnerable. Talking about, um, whether it's love and what that means to me, or what that means to people with disabilities. My role in my family as kind of the person with the disability and how I understood that role to be different than I understand it now. And you're just challenging parts of how people perceive me and perceive disability that I think was different from how I had often talked about my life. I've often talked about my life in terms of triumph and resilience and strength and hope and which are all very important. And whenever I talk about disability, those are the kinds of ideas that I want to encapsulate it in. But at the same time, I couldn't talk about those things with autos and talking about the vulnerabilities that I've had to come to terms with. And when I talk about Look Both Ways, I'm not just kind of, I guess, acknowledging, um, being hit by a car aspect of my life. Right. Kind of the admonition, uh, you have to look both ways before crossing the street, but actually looking at all parts of your life. And in order to have a full understanding of who you are and where you are in the world and how you've gotten to where you are, um, you need to look in all directions and see all sides of it.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yeah. And it seems like it's a never ending path. Right. It's not like, okay, so I wrote these memoirs, I was able to tell my story and then everything was wrapped up and forever more. I'm struck by the fact that when you decided to write Look Both Ways, it sounds like you were in the midst of another challenge. And I'm sure that the ongoing challenges continue in such a way as they do for all of us, but especially too, for you, some of the physical challenges that still stem from that accident. And that's not something that you ever are able to rid yourself of. For listeners that aren't familiar with your story, how would you describe your story to them?

lity. So this was way back in:Dr. Andrea Bonior: Oh, my goodness. So you're not busy at all? I mean, the word remarkable doesn't begin to describe what it must have been. The trajectory from those months in the hospital to actually imagining how much you were ultimately able to thrive. I'm struck by that notion of how jarring, emotionally, so many aspects of this, of course, must have been. But the idea that maybe your friends and your peers might find your actual presence in the classroom to be scary or traumatic, and as you said, you were a product of that culture as well. I'm guessing it has to do with sort of the way that folks with disabilities are made to feel like others. Right? Like you went from a pretty typical kid with peers and friends and everything, and all these activities to being a twelve year old who, just by existing, was told, well, maybe your existence is a disruption.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: Right. Exactly.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Uh, do you have memories of that time, of how you coped with that, how your friends responded or didn't respond, or just emotionally what that was like for you.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: I sure do. I remember being discharged from the rehabilitation hospital and being afraid. I remember being afraid that I was going to be leaving a place that offered almost like a cocoon like existence where everybody who was around me had experienced some kind of trauma, some kind of life altering circumstance. And to be kind of discharged into a world that I knew firsthand was not going to see me the way that I saw myself, that was frightening. And then that fear was kind of reified by the very first experience I had with the world and with kind of bureaucracy in general trying to return to school and getting some resistance that I feared I would get but was hoping that I wouldn't. Ah, this is really impactful and um, jarring for anybody at any age. But when you're twelve years old, when you're just full of so many anxieties and wanting to fit in anyway, that was really hard. I think that some of those beliefs came from adults and um, when I ultimately returned to the classroom, like my friends and my peers, they were less, ah, I guess less concerned about those ideas than the adults were. M, but it was difficult. And fortunately some of my friends had come to visit me when I was in the hospital. They came to see me. Not everybody felt comfortable doing that, but a number of them did. There was a lot of community support for me and a lot of being kept up to date as to what my progress was in order for me to even get home. There was a tremendous community outpouring of, um, your support and love and, um, resources. We had to make a lot of modifications to my home, renovations to my home that was completely community driven process. So just friends of our family did all the reconstruction. The day that actually we have videos here in my house, VHS, uh, recordings, uh, the day that my family broke ground and the renovations that needed to be done. And my neighbors were all pitching in and helping to dig the ditch or whatever they were doing, right? So it was just like, literally like a scene out of a movie, which actually turns out to be the gator went down that cushion the blow a little bit. But I didn't know what to expect. And just trying to internalize an identity around disability that took me a very long time. That was not something that came easily or without tremendous internal struggle to go from just living with disability. That was how I was discharged from rehabilitation as somebody who could learn to live with disability as opposed to somebody who is disabled, right? Somebody who could um, incorporate the identity of being disabled into who she is. And that took a really long time and I think there's an important distinction between those two things that we're not just talking about accommodating my life. Just like the world used to accommodate itself to offer some kind of modicum of acceptance to disability. That was kind of how I was taught to understand my life and rehabilitation. But to change that, to feeling proud of who I am and to know that disability is not how it has always been contextualized or described as some source of weakness or, um, a population that is not worthy of our respect or inclusion. I view disability very differently now, and I understand disability to be kind of the culmination of humanity and resilience at its apex. Right. You need to be strong in ways that I think life doesn't always understand strength. You need to be resilient in ways that life doesn't always value resilience and be hopeful in ways that life doesn't always value hope and, uh, problem solve on a daily basis because the world is just not designed for the needs that you have. Be creative and how you approach the problems that you encounter without feeling completely diminished by them. Uh, so those are all really important virtues and aspects of the disabled identity that I think don't get nearly enough attention.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Just the need for adaptability and problem solving, I'm sure just on an hourly, if not minute to minute basis for our listeners. How was that process to go from having full mobility as a typical eleven year old to coming home as someone who was quadriplegic and really starting from scratch? Obviously, it sounds like you had a lot of support, but I'm imagining that even the tiniest things that you didn't even think about as an eleven year old before the accident became suddenly a problem that almost at times, could have felt insurmountable. Where did you draw upon the strength to figure out some of that everyday stuff that the rest of us don't really think about at all and that you might not have thought about?

Dr. Brooke Ellison: Right. Yeah. Well, I remember being in the hospital and kind of staring up at the ceiling at night where I do a lot of thinking and feeling frustrated that I didn't value just mundane aspects of life as much as I could have or should have. Like, I didn't place as much attention, um, on what it felt like to rub my fingertips on the carpet and really remember what that felt like or what it felt like to stretch or to do all the things that characterize life. Really insignificant things. Uh, and they are so insignificant that you don't take the time to pay attention to them. And when you don't have them, it's just like, wait a second, there's a tremendous sense of loss. So that took a while. That took a while. And it becomes quite astounding the number of things in your life on a daily basis where if you can't do it yourself, you have to ask other people to help you with. And, uh, that was a hard thing for me to come to terms with everything from deep impersonal, um, aspects of daily life and care to just getting a drink of water. You have to learn and I go into some depth about this and look both ways about your need to be patient in ways that you couldn't have ever imagined having to be patient, like waiting even for your next bite of food, or waiting for your next breath to come. All of these things are really, really hard. And it could seem completely overwhelming when talked about in this way. I can understand how it would seem completely overwhelming, but in order to get on with my life and in order to move forward, I had to learn to remove myself from those things that seem overwhelming. Right. I couldn't think about any number of those aspects of my life that I had to just abdicate to somebody else, because if I thought about them on an individual basis, it would be completely overwhelming and almost defeated. So I had to understand my life in terms of what are the things that I can't do anymore, put those aside and just move forward on the things that I could still do. And that kind of, uh, fostered my understanding of hope and what that has meant to me and how I have deconstructed that construct into something that I could operationalize and put to use in my life. Um, and that was really difficult. That took a bit of time, but I think up until that point, I tried to return to my life as I had known it as much as I could, without thinking about what I had lost and just focusing. On the things that I still had, whether that was playing with my brother, watching my brother, um, play basketball or doing crossroad puzzles with him. Um, spending time with friends, going to movies and the movies with friends, or going to the mall back at the time when malls were, um so I tried to integrate as much of my life as I had known it into my new existence. Right. Not thinking that my life was totally different, but still had vestiges, um, of what it had been.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Mhm, yeah, that idea of breaking it down sounds important. The small types of things, rather than, okay, here's the big picture, and here's all the stuff that can be totally overwhelming. I mean, your life changed so qualitatively and quantitatively in an instant. But I love that idea of going smaller and saying, you know what, I can do a crossword puzzle with my brother and maybe tell him he's wrong on this answer, change it, and that kind of thing. And that interpersonal connection seems so important, too. And I know that one of the themes, really, that you return to a lot in look both ways is the notion that some of your struggles though some listeners might feel like they're so qualitatively different than their struggles, but some of them might just be a matter of degree, right? That those same things that you talked about, the need for being able to problem solve, the need for looking at reality and being able, one small step at a time to overcome a barrier, the need to be understood by other people for who you actually are these are fundamentally human struggles that apply across the board. And I think it really speaks to the notion that some of the triumphs that you've had really can apply to other people who are facing obstacles that don't seem nearly as devastating, but nonetheless require some of the same the same types of psychological the psychological characteristics to keep going.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: Yeah, I think that's exactly right. So I tried to be as forthright about that very idea as I could be in the opening pages of the book that when I started writing, Look Both Ways. I was pretty committed to it not being a book about disability, right? Like, I didn't want it to be cast aside as just a book about a specific population. Because I know, irrespective of how important people with disabilities are to the world, their voices are not necessarily heard as frequently as they could be. But at the same time, I think disability is an important and very obvious representation of the challenges that everybody faces. Right? It forces a level of, uh, creativity and strength and problem solving and resilience that I think getting through almost any struggle that we encounter requires. What's interesting, I think, is when we're experiencing these challenges in our lives, things that are completely life altering and difficult to come to terms with, we feel very isolated, we feel very marginalized, and like, nobody could possibly understand what we're experiencing. How could the world continue to go on around us as it's gone on when our lives have been so turned on their heads? That was certainly how I felt at the time of my accident. But what's interesting is that the challenges that we face are really, like, one of the only universals that you've had to be faced and that we're all going to experience some level of, uh, hardship or difficulty that seems like it's going to be too difficult to bear, or it's going to be so life altering that our lives thereafter are going to seem unrecognizable or not at all relevant to how we had typically understood the world. But we could find a path forward. Right? Disability you have when you experience a disability or like, uh, an accident or injury like my own, it's either you find a way forward or you wither and cease to exist. That was not an option that I was going to be satisfied for my life. So, um, in talking to people about look both ways or about my life over the years, it's very often people who have. Experienced things that are wildly different from being hit by a car and being left with quadriplegia. But uh, the kinds of struggles are very much the same. The kinds of internal challenges and trying to understand a new identity are very much the same. And the kinds I think skills and toolkits that you need to rely on in order to get to go forward are just identical. And that's really been exciting. And I think there's a sense of commonality in that struggle and in that humanity that I feel very fortunate to be a part of. And I don't know if I would have seen that with such clarity and with such a profound, um, residence had I not had the injury that I had. I don't know if I would be out here talking about an ability to overcome difficulty and to deal with challenge and how to be resilient and how to be hopeful or not for the struggle that I face. Right? I think that's a really important aspect of, uh, resilience and hope that it's very difficult to understand absent of the challenges that we face. Right. They're not constructs that just kind of present themselves out of nowhere, but are very much often the outcome of the struggle that we undergo. And I feel very fortunate as a result that I've had these new insights on how life can be lived.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Mhm, I'm sure there are people listening that say, oh, but she's got something I don't, right? For her to be able to summon that level of hope, that level of resilience, that level of motivation, energy, perseverance, there are people who might truly be saying to themselves, there's no way that I've got that or even a part of that. Right? I mean, your story, there's no doubt, it's so remarkable and clearly what you have achieved, even had you not had the challenges, many people would be looking up to, uh, graduate. So Harvard, I'm kidding. But what would you say to folks who say, oh no, there's just something so rare and unique about the way that you were able to find hope. You're made of stuff that is just so phenomenally, extremely different than what I've got. That here I am, facing a challenge that is 2% of what you face and I just feel like I don't have it in me. I can't see the hope and I'm so fascinated by hope. My dissertation was in part on hope and I love this construct. And you obviously summoned it from such a dark place. You found that light and that light really did amazing things. So what would you say to somebody who says, well, you have something that I don't I don't think that I could follow this example, that I don't think that I could summon light in the darkness.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: Well, thank you for saying that, number one. Thank you for recognizing that. I do, I appreciate that very much. Um, I would say that that would be the exact same thing I would say to somebody 33 years ago if somebody had told me that I was going to experience a devastating accident that would leave me, um, quadriplegic on the ventilator, um, I would say those very same things. I don't have the wherewithal I don't have the strength or, um, the self confidence or whatever. It takes the grit in order to move forward with that. I think that is often how we view challenge in our lives. It's going to seem insurmountable, but we can find a way forward. And that's not to say that everybody does, right? We all know that there are some people who don't or can't or feel like the struggles in life are too much to bear. And of course I understand that. But I also believe very strongly that, uh, there is a path forward. I never would have imagined living as much of my life from the vantage point of a wheelchair. Right. I teach medical ethics and I often actually, every semester I ask my students, do we talk about many different classic cases in medical ethics where people who have undergone devastating diseases or diagnoses feel like their lives are over. So I have a conversation almost like a thought experiment with my students asking about what would, for them would constitute a life not worth living. And they say things like, oh, m, if I were connected to tubes and tube machines, or if I couldn't do the things that I think are important in my life, or if I were dependent on my family to care for me, all these things would make their lives, uh, not worth living. And then over the course of the semester, and I share different parts of my life and experiences that I've undergone and ways I've lived my life and how I think the conversation around disability and around ethics needs to be modified. So we're not always thinking in those terms. Like, by the end of the semester, they think about things very differently. Right. And that not only can we find the resilience and the strength to continue with our lives, and if we find look for avenues, uh, of continued purpose that might be different from what we had originally anticipated for our lives were no less important and valuable. And then kind of helping to create a society in which people don't feel like they are unmoored or without any kind of connection to reality when they undergo these life altering situations, whether it is disability or some kind of diagnosis or something completely different from that. If we have a strong social support network that I think we don't often give enough attention to, then it makes the shouldering of these kinds of experiences that much easier. And I don't think that we talk about that nearly enough. I don't think we have built a society or a community where we feel like we can talk about the struggles that we encounter, how we need each other, why we live in a very kind of self reliant based orientation to how we get to where we are. And I think disability is a very profound example of how that really needs to be rethought. People with disabilities are very much the product of their relationships with those they have, and that should not be thought of as a weakness or something that is aberrant, but something that is fundamental to the human experience.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yes. Oh, there's so much there. And what brings to mind it brings to mind loneliness when you talk about the social support need. And in fact, the Surgeon General, just yesterday, it came out finally, right? Yes. Great Britain had declared loneliness an epidemic several years ago. And I know our Surgeon General has done a lot of work on loneliness over the years and is an expert in it. And it's always been relationships has always been one of my areas of interest and passion and expertise. And I was so glad to see the US government come out and say, this is a crisis scenario. Right. People feel more disconnected now than ever before. Loneliness levels have been rising precipitously for a couple of decades now. The role of technology, the role of the pandemic, they can all be seen. Right. And I think, just as you said, we don't talk about the role of social support nearly enough, how fundamentally crucial it is for physical and emotional health that it is not a luxury. Right. It is as important as flossing your teeth. The data says if you are lonely, that's equivalent to being a heavy smoker in terms of the health effect.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: Exactly.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: And so the social support and the way that you speak of how the community came and rallied for you, of course there were snafus like, oh, what about the classroom? It's just doable and all of that. But the idea of refitting your house to be able to accommodate your needs, and the idea of friends visiting you in the hospital, even if they were a little scared, even if their parents didn't really know what to say, things like that coming together. That role of social support is such a forgotten factor, I think, by a lot of people. So I'm so glad to hear you bring it up. The other thing that really struck me in listening is just how much we are bad at predicting how something would affect us. And I know that the happiness research talks about that in the opposite way. Right. What we think would make us happy turns out to not really be the case. What you're speaking of is like, okay, I would have assumed that this would be so fundamentally unmoring for me, too, when I was ten or eleven years old, I would have assumed I couldn't persevere, I couldn't be able to overcome such a scenario. And in fact, obviously that was incredibly wrong. And I love what you're pointing out to our listeners that many of us might be saying, oh, well, I just don't have something in me, or if this happened, I would just not be able to find a way. And I work with a lot of people suffering from grief and loss, and I think they have a very similar experience. They say, I could have never imagined that I could start to move through a loss that's devastating. And yet I am. I'm not getting over it. I'm not moving on. But I am moving through it. I am carrying it with me. I am incorporating it into my life. I am growing bigger around it. And had somebody asked me two years ago if I'd be able to cope with such a loss, I would have said, no chance. Where would I even begin? But I am putting 1 hour at a time as my agenda, and I'm able to just hour by hour do the next thing that I need to do.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: Exactly. And you have to understand it in that really kind of step by step way where it doesn't happen overnight. Right. There's a transition from trauma to ongoing struggle to acceptance to ultimately resolution. That takes time. Doesn't happen right away. And there is grief that comes along with experiencing loss, but that grief is not indefinite. Right? And, um, that was something that was really important for me to understand. And even to this day still, there are days where I grieve what I have lost or what I things that I would like to be doing that I can do. And that's just part of humanity, that's part of living life. We all do that. But I think also we tend to have visions for our lives about what they ought to be or how they would have been. And I do this. I don't know if there's any day in my life where I don't think about, uh, what would have been if I didn't cross the street, if I didn't cross Nichols Road that day. What would my life had been like? As if that is any more real or any truer a life than the life that I live right now, or any more valuable life than the life I live right now. And I think we do ourselves a tremendous, uh, disservice when we think about our lives in some idealized term as this is the right life and the one that we're living is the wrong life. And that took me a long time to come to realize.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Mhm. Yeah, like I always tell my clients when they're sort of ruminating on these alternate path, it's like history doesn't have a control group. Right? Had you not crossed the street that.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: Day, still counterfactual.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: What would have happened. I think so many times the need to undo something in our past is so visceral because it can make the world make sense, right. It's like well, if this didn't happen, then everything would make sense. And I imagine something like the accident that you suffered that's so profoundly extreme, because it's literally something happening out of the blue in a split second that was completely unpredictable, unforeseeable. And I think that's so fundamentally scary for people. We would rather make sense of the world and say, well, if I hadn't done this, then everything would have been okay. Or a lot of times what I see is it's easier to blame ourselves or blame other people, because then that would make it make sense.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: Yes, exactly.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Did you ever experience any of that in terms of sort of the self blaming aspect or the over focusing on the blame in some other way? Of maybe that makes the world feel more predictable and the world makes more sense. If only I hadn't made this decision of doing this, then the world can make sense again.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: Absolutely. Uh, probably every day of my life for maybe 25 years after my accident. This was the pivotal M event. This was the aberration, this was the inflection point at which my life went wild, dry, as you said. That makes it manageable, that makes it easier to try to digest. It actually wasn't until I was writing Look Both Ways, where I thought about this very deeply. It's actually one of my, uh, favorite passages in the book, actually, in chapter one, where I talk about how people can think about my accident and think about all of the trauma to my body in ways that are very kind of easily quantified or easily talked about. Because when you do that, it makes it manageable. It can help you distance your own self from somebody else's experience. Right. Like, oh, and I talk about this in the book, that there's some likelihood of being hit by a car. But, uh, in this particular instance and this specific orientation in exactly this way, the odds are even much more remote. Right. So it makes it easier for people to distance themselves from these things that we fear. And I think the same thing holds her when we view our lives in terms of these seven moments that throw things off course. Right. Because it makes it easier to view challenges in our lives, uh, as unlikely or purely discreet or isolated in nature, when that's just not the way life is. Right. It's full of challenges. Each day creates some kind of set of experiences that if, uh, those events had happened, your life would have gotten some other course. But to think about all the infinite possibilities that our lives could take would just be overwhelming. So there's not always just one specific instance or one specific event that makes our life what it is. The culmination of all these events that make us who we are. And to think about all the different possibilities is just impossible.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yes. Truly impossible. So this is a strange, full circle moment as I feel it because listeners know. Uh, a couple of months ago, we had an interview with Dr. Mary Anne Gray, the founder of the Hyacinth Fellowship, who unfortunately has recently passed away. Since our interview, um, and the Hyacinth Fellowship was a supportive community is a supportive community for those who have unintentionally caused harm. And it strikes me that Dr. Gray's tragedy of her life as a young adult was that she was driving and a child ran in front of her car and she hit and killed that child. And we had such a moving conversation about being on the other side of that, about the shame and the guilt and the trauma of accidentally causing harm. And I can't help but reflect upon just what a complimentary piece this is because we are dealing in this very conversation with being on the other side of such a tragic event. And so I can't help but wonder, and listeners should know I got your permission to ask this, but I can't help but wonder what your perspective and emotional relationship has been over the years, or was at the time, to the idea of the person who hit you or the person themselves and what that process has been like for you.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: Sure. So, unfortunately, I never had a relationship with the gentleman who drove, who hit me. And that was not something that happened by choice. It was not a relationship that ever came to any kind of fruition. I have not spent my years feeling resentful or any amount of anger towards him. It, um, was my instance just an accident? And he didn't see me, I didn't see him. But I think even if that weren't the case, even if there was something more nefarious at play, I could not have moved on with my life. I don't know if I could be where I am today, if I harbored resentment or anger. Um, that's kind of placing the onus of, uh, life's events on just a person right. On, um, on something that seems tangible when, you know, the kinds of things happened in our lives are a lot less tangible than that, often a lot more circumstantial than that. But I'm sure the enormity of the circumstances affected him profoundly, just as they, they affected the, you know, Sarah was walking home with about twelve other friends and, you know, I was the only one who had injured and I know that they experienced things deeply emotionally and suffered with a lot of trauma after, uh, experiencing that. And even members, m, of my family who were not directly affected, everybody there's a, uh, feeling of guilt or m why Brooke and why not anybody else? Right. All of these things, uh, I think we tend to view our struggles in isolation, but many people are affected. So I don't know exactly what he had, what his life has been like ever since, but I know full well that any accident doesn't just affect one person, that there's a deep struggle that many people experience. Just like reflecting on my life and knowing ways that I've either inadvertently or sometimes even deliberately hurt people who I love. Right. Like you live with that. That's something that you carry with you for a very long time. Um, it's part of humanity, unfortunately, I think. Yeah, I do it. We all do it.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yeah. And that speaks so much to just the ripple effects of any event like this and who we tend to focus on as a culture. And then we don't necessarily see the other layers. And I think that's one of the lovely things about the ways that you've told your story is that you take the other layers into account and you think, hey, what would my family think about this being part of their story? And how can I be respectful there and also understand their perspective and what they went through? Because I think so many times our society is set up to say, okay, well, here's the hero of the story and here's the villain of the story, and these people had nothing to do.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: With it at all.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: In reality, it's always that interaction, it's always that, uh, different perspective. You have no doubt in sharing your story, just given so many people the strength to think about their own challenges. And I think that's what you see over time as people come to you and share your story. I know that so much of what we've talked about today is how these lessons can apply to anyone, but I want to end on specifically thinking about how all of us can be better advocates for those with disability. And as the numbers of folks affected by disability are continuing to grow as the stigma, still, in some ways people aren't even aware of the implicit biases that they have. The ways that our society and our structures are set up to be completely not only discriminatory, but sort of creating a system where we view people as others. Right. What can the average person listening do in their daily lives to be part of the support, part of the help, part of the moving forward for folks who are living with disabilities and not be part of the problem?

actually just earlier today,:Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yeah. It feels like it all comes back once again to that idea of connectivity among ourselves, um, being able to look at each other in the whole sense of the person and to not wall ourselves off through fear. To not think that, oh, because somebody is different, I should stay away.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: That's them.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yes. To be vulnerable enough to be willing to connect and get the meaningful connection and help create a sense of belonging, um, for all of us.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: Right. We don't lose out by doing that. Right. We all gain.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yeah. Immensely gain. Well, I know our listeners and I have gained so much from this conversation. Brooke, I appreciate so much you're having taken the time and one more time. Yeah, one more time. Tell folks where they can get your book, where they can see more of your work.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: Thank you. Look. My book is look both ways. It's available on Amazon or Barnes and Noble. How you prefer to buy your books, please. I'd love to hear from you. Uh. My website is Brooke ellison.com. So brooke with AME. Brookellisonm.com, lots of avenues for engagement there. And then, um, on social media, all my socials are connected to my website. So I'd love to hear from you.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Wonderful. Thank you again so much.

Dr. Brooke Ellison: Thank you. It was a pleasure to talk to you.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Such a pleasure for me as well. Thanks for joining me today. Once again, I'm Dr. Andrea Bonior, and this has been Baggage Check, with new episodes every Tuesday and Friday. Join us on instagram at baggage checkpodcast. Give us your take and opinions on topics and guests. And you know, you've got that friend who listens to like, 17 podcasts. We'd love it if you told him where to find us. Our original music is by Jordan Cooper, cover art by Daniel Merity, and my studio security, it's Buster the Dog. Until next time, take good care.