Shownotes

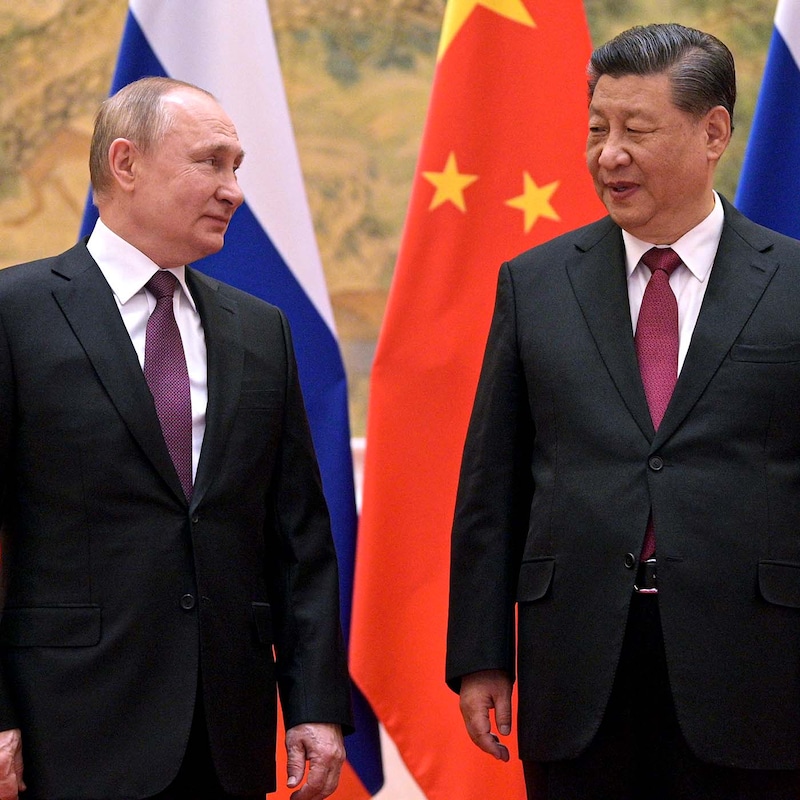

The war in Ukraine has upended what many of us thought we knew about the world today. Whether we’re thinking about Russia and Europe or China and Taiwan, it seems like the range of possible outcomes in conflicts around the world has expanded in unsettling ways.

In the midst of all this, Watson Senior Fellow Chas Freeman thinks there’s one key concept we’d all benefit from getting reacquainted with: ‘spheres of influence.’ Chas Freeman is one of America’s leading experts on US-China relations, and a wide-ranging thinker on international affairs, diplomacy, and statecraft.

On this episode Chas talks with Watson Director Ed Steinfeld about how thinking in terms of ‘spheres of influence’ could help us better understand the world. In fact, it goes beyond just understanding the world. Chas thinks that concept of ‘spheres of influence’ – with a little tweaking – could actually help global superpowers like the US and China navigate and de-escalate conflicts of the future.

Transcripts

[MUSIC PLAYING] SARAH BALDWIN: From the Watson Institute at Brown University, this is Trending Globally. I'm Sarah Baldwin. The war in Ukraine has upended what many of us thought we knew about the world today.

Whether we're talking about Russia and Europe or China and Taiwan, it seems like the range of possible outcomes in conflicts around the world has expanded in a terrifying way. In the midst of all this, Watson senior fellow Chas Freeman thinks there's one key concept we'd all benefit from getting reacquainted with, spheres of influence.

CHAS FREEMAN: This is something really basic in international diplomacy and I think it has deserved a great deal more attention than it's gotten.

SARAH BALDWIN: Chas is one of America's leading experts on US-China relations. He was also an ambassador to Saudi Arabia during the Gulf War and he's a wide ranging thinker on international affairs, diplomacy, and statecraft.

On this episode, Chas talks with Watson's director Ed Steinfeld about how thinking in terms of spheres of influence could help us better understand the world. In fact, it goes beyond just understanding the world.

Chas thinks it might with a little tweaking, help global superpowers like the US and China navigate and de-escalate conflicts of the future. Ed and Chas started with a little history behind the concept and why it has more to say about current events than you might think. Here's Ed.

EDWARD STEINFELD: Chas Freeman, welcome to Trending Globally.

CHAS FREEMAN: Very happy to be here. Nice to see you, Ed.

EDWARD STEINFELD: I want to begin by asking you, what is a sphere of influence?

fluence was first used at the:EDWARD STEINFELD: Right. It feels a bit almost like an archaic term from the imperialist era.

CHAS FREEMAN: Well, in a sense it is and on the other hand, it's very much behind the current trouble with Ukraine. I should say that we think of it usually in political military terms, and that is indeed the usual form it's taken historically.

But what we're seeing now are multidimensional spheres of influence, zones of exclusion for economic or technological purposes. For example, you can't have Huawei, the Chinese telecommunications company, anywhere near you. And similarly, we're seeing--

EDWARD STEINFELD: So that's an American declared sphere of influence over technology.

CHAS FREEMAN: It is and it's global. And of course, that's one of the great developments of our time that after the end of the Cold War, which basically involved two great spheres of influence, if you will, one Soviet, one American led.

After that, the United States is essentially without even realizing it, extended the Monroe Doctrine to the entire world up to the borders of China, Russia, Iran, North Korea. They're basically the only parts of the world which are nominally excluded from our presumed right to supervise and participate in decision making by other states.

So in the case of Ukraine, even though Ukraine did not join NATO, has not joined NATO and is not therefore an ally, in Two Thousand and Eight George W. Bush proclaimed an intention to incorporate Ukraine and Georgia into NATO.

And by doing that, he in effect declared that they were within an American sphere of influence and we've been behaving that way. The immediate result of this proclamation was the Russian decision to ensure that Crimea, which is the site of the major Naval base on the Black Sea at Sevastopol, remained in Russia not in an American sphere of influence. That would have crippled it.

So in effect, the Two Thousand and Eight Ukraine declaration led immediately to within six years to the Russian annexation of Crimea. And following that, we began to do a whole range of training, equipment transfers, assistance and reorganization, military sales to Ukraine, treating it very much as part of our sphere of influence, if you will, a sphere of influence which was overtly aimed at Russia.

So this concept spheres of influence protection from other great powers by projecting your own influence or denying it to them, this is something really basic in international diplomacy. And I think it has deserved a great deal more attention than it's gotten.

EDWARD STEINFELD: I have two questions about the concept, particularly as they relate to the war in Ukraine right now. First question is, you've been speaking primarily about what the United States has done and that makes a lot of sense.

But what about the role of and the agency of the smaller nations that are involved in these spheres. So what about the agency of Ukraine or a variety of other countries that are responding to these claims?

CHAS FREEMAN: Well, I think that's a very important element of this. Ukraine is for very sound reasons, like the Baltic states quite Russophobic and it wants protection from Russia. Now you can get protection in one of two ways. It can invite in another great power, the United States through NATO, to offer military protection. Or alternatively, it could deny Russia reasons to want to take it on.

The alternative that was used in Nineteen-Fifty-Five to free Austria of potential incorporation into a sphere of influence, whether Western or Soviet, was the Austrian State Treaty of that year in Nineteen-Fifty-Five. The US, the Soviet Union, Britain, and France all agreed that Austria should be independent provided it treated its minorities fairly. But that Austria should be neutral and not join either the Soviet or the American bloc.

That has worked very, very well. Ukraine has had that choice from the beginning. And it has for various reasons, not wanted it. But I have to say that it's been encouraged not to want it.

And when in fact, it began to seem that it might pursue such an option of a neutral position, we helped stage a coup that overthrew the democratically elected incompetent and corrupt government, but still democratically elected and installed one that had the opposite idea of joining our sphere of influence.

So there's a lot of history here and I'm afraid we have at the moment secretary of state who says that the United States does not recognize spheres of influence. But at the same time insists on both the Monroe Doctrine explicitly and implicitly on an American sphere of influence in Ukraine.

Ukraine has the right, he says, we say to choose whatever course it wants as long as it's our course. If it chooses the Russian course, then we have to back it against the predictable Russian reaction. Well, this is classic sphere of influence, diplomacy if you will, and it's also a very good way to start a war.

EDWARD STEINFELD: I want to come back to the agency of small nations question in just a moment, especially with respect to East and Southeast Asia, which of course, have also written about.

But from the perspective of great powers who are extending these spheres of influence, I'm interested in the idea or at least trying to navigate between two kinds of arguments. One argument about the situation, the war in Ukraine today, one argument says that there's a security dilemma and US actions and the expansion of NATO deepened security concerns for Russia.

And Russia has responded to those security concerns by trying to extend its sphere of influence back to Ukraine, and perhaps creating some kind of buffer along its borders. And I think there's a certain logical consistency with that argument.

And then there's a different argument that says, regardless of what the United States or NATO did, Russia is extending its sphere of influence because of a narrative about grievance and humiliation. Of course, grievance and humiliation seems to be the order of the day in politics globally. But that there is this narrative and national identity, which is driving a sphere of influence. And how do we navigate between those two explanations?

CHAS FREEMAN: Well, I'd say in the case of the Ukraine issue that what we saw was a sequence of events, which began as I suggested earlier, with in effect an American proclamation of a sphere of influence in Ukraine, which we then proposed to formalize through a membership for Ukraine in NATO.

I think the Russians began not with an objective of establishing their own active sphere of influence but perhaps a passive one, denying Ukraine to the American sphere of influence.

I think somewhere along the line however, perhaps these other complex human factors that you mentioned, Russian romanticism about Kevin Roots as the origins of their civilization. And other factors. Laments about the loss of empire and so forth came into play.

So here we have a problem and we focus on the personality of Vladimir Putin, who is clearly a very complex individual. Prior to February Twenty Twenty-Two, he was widely regarded as very much a realist, very much a practitioner of realpolitik and quite skillful at it.

Examples include the use of a minimal investment of force in Syria to establish a Russian zone of influence in the Middle East that had disappeared earlier. And now post February Twenty Twenty-Two, he's turned into the usual enemy we have, which is Adolf Hitler in disguise. Irrational, brooding, subject to some sort of morose nationalist, emotional, impulse that overrides reason.

I think this is all too simplistic. It's the same man. He obviously combines both elements. I think he expected that he would have an offer for negotiation of a security system in Europe that would be reassuring to Russia. Instead he got stiff armed.

And at that point, instead of escalating elsewhere, which is what I suspected he was going to do about putting submarines with hypersonic missiles off the US coasts or something, he went for Ukraine.

And he went for Ukraine apparently on the basis of extremely bad intelligence. One of the problems of autocracy, and he's clearly an autocrat, is sycophancy of subordinates who don't want to tell what you don't want to hear. And I don't think he was told what he didn't want to hear.

In any event, he made a colossal error. And to my mind, it is on a par with Nicholas II, the last tsar's decision to go after Japan in Nineteen-Fifty-Four, greatly underestimating Japanese competence at warfare and causing collapse in Russia that culminated whatever 13 years later in the October Revolution.

I think Mr. Putin may have made an error of comparable consequence. Just a final note on this and that is this, should not be foreign to us. When the Soviets put a presence in Cuba, we enforced the Monroe Doctrine.

If you could imagine let's say, the Chinese or the Russians training the Mexican army to fight us, you can imagine what sort of reaction we would have. So I think there's a problem here, which goes back, perhaps, to the period of American unilateralism that we just don't listen to our adversaries sufficiently.

We offend them, we expect them nonetheless to cooperate with us and we don't really spend much time understanding their perspective. Instead, we declared that they're irrational.

In my experience when you say that an adversary is irrational, all you're saying is I'm not going to spend the time to try to figure out why this adversary is behaving the way it is. And I think that's how we got in the Ukraine trap. It does not excuse Mr. Putin's terrible mistake or his abominable behavior, but it is an explanation of why that happened.

SARAH BALDWIN: Up next, Ed and Chas turn their attention to Taiwan.

EDWARD STEINFELD: If you like this conversation, check out our other podcasts from the Watson Institute. From ancient history to current events, if you're interested in how the world works we probably have a show for you. We'll put a link to all our podcasts in today's show notes. And if you're not a subscriber to Trending Globally, you can find us and subscribe wherever you listen to podcasts. Thanks.

SARAH BALDWIN: Ever since Putin invaded Ukraine, one question that many experts have been asking is what might this conflict mean for Taiwan. It's another highly contested region, involving a superpower that doesn't exactly see eye to eye with the West, China.

For those who need some brushing up, Taiwan is a democratically ruled Island off the coast of China. In Nineteen-Forty-Nine when the Chinese Communist Party took control of mainland China, the opposing military retreated to Taiwan. Since then, it's been depending on who you ask, either an independent country, a territory that rightfully belongs to the People's Republic of China or the only legitimate government for all of China.

However it's been defined, it's a territory that's been under the US' sphere of influence for decades. And while the Cold War is over, the tension between the US and China over Taiwan never faded. It's one of the most contentious regions in the world and conflict in Taiwan is seen as one of the biggest threats to global peace today. Ed and China's got into all of this and more in the second half of their conversation. Here's Ed.

EDWARD STEINFELD: So let's turn to Asia and the Indo-Pacific. How does the sphere of influence perspective illuminate the Taiwan issue?

CHAS FREEMAN: Now the Taiwan question is very interesting from this perspective in the sense that its origin is the retreat of the defeated Chiang Kai-Shek army across the Taiwan Strait to the newly recovered province of Taiwan, recovered in Nineteen-Forty-Five from the Japanese and governed from Nanjing for four years before it was severed from the mainland by our intervention in the Taiwan Strait with the 7th fleet in Nineteen-Fifty.

Chiang Kai-Shek forces and Taiwan, the Republic of China, were very much part of our sphere of influence in the Cold War. They were part of our bloc. We insisted that Taipei, not Beijing, represent all of China and the United Nations Security Council and General Assembly. And they did until Nineteen-Seventy-One. Taiwan has very much remained in the US sphere of influence.

And the Chinese effort is to remove it from the American sphere of influence. We have to understand a little bit of Chinese history to understand the emotional intensity that this sphere of influence concept conveys.

At the same time that the Europeans were carving up Africa, they were busy carving up China into spheres of influence. The French got Vietnam and the area near Vietnam. The British got the Shanghai and the Yangtze Valley. And the Russians got the North and the Germans got Shandong and then lost it to the Japanese and so forth and so on. The Americans of course, managed to piggyback on all of the above.

So the sphere of influence on Chinese territory is a major element of the Chinese emotional reaction to what they call the century of humiliation. The fact that there's still a sphere of influence operated by the United States on Chinese territory is a red flag, really.

There are many other issues here. There's the issue of self-determination by Taiwanese, perhaps many of them not wanting to be Chinese and that's their right as long as they understand that it would provoke a war and that the only entirely predictable result of such a war would be to leave Taiwan as a smoking ruin and cost it the very democracy it wants to preserve.

But I think thinking of it in terms of spheres of influence opens opportunities for settling the issue. Could Taiwan be neutralized? Could it remain politically allied with the United States? Perhaps. Economically allied with China? Technologically straddling both worlds, perhaps. But militarily neutralized, not to be used by China against anybody, by the United States against China.

I think it would be interesting to look at it with fresh eyes from this perspective always bearing in mind of course, that we're dealing with real people not these are not tin soldiers on a fake battlefield. People have feelings, both on the mainland and in Taiwan. And we have made promises that we cannot shrug off without consequences.

EDWARD STEINFELD: For example?

CHAS FREEMAN: When we normalized relations with Beijing, meaning we recognize that it rather than Tibet was the seat of the government of China January 1, Nineteen-Seventy-Nine, we acceded to three conditions.

First that we ceased to recognize Tibet as the government of China and break relations with it. We did that. Second that we withdraw all our military forces and installations from the Island. We did that. And third that we not have any kind of official relationship with Taiwan, and we disagreed about arms sales in that context.

But those three conditions were observed for 40 years. During that 40 years, tensions in the area diminished to the extent that Taiwan was able to democratize. I consider that a great success of the bargain we struck with Beijing in Nineteen-Seventy-Nine.

Now we've basically salami sliced all these conditions away. We now champion Taipei internationally and we punish countries that switch from Taipei to Beijing as we have done ironically, but if you're El Salvador and you do that, apparently that will get you in trouble with Uncle Sam.

We do have troops on Taiwan now training Taiwanese forces and apparently doing so for offensive purposes, presumably counter offense, offense in response to an attack by the mainland. But whatever the purpose, we've broken our word.

We have a building in Taipei that flies an American flag and has Marine guards and it costs $230 million. That is indistinguishable from an embassy. We send cabinet members to Taiwan as much or more than we do to many other places which we do recognize as full members of the international community.

So from the Chinese perspective, we've walked back every commitment we made and increasingly you hear the Chinese saying this. And this gets me back to Ukraine. It was obviously a mistake not to pay attention to what the Russians have been saying for 28 years about the fact that at some point, their patience would snap.

They would not put up with a country on their borders with missiles that could strike Moscow in five minutes, which is their concern. We didn't listen. We ignored them. I think if you ignore a great power that's passionately objecting to something, you're taking a measure of risk. It doesn't mean you have to agree with them, but at least you have to address the issue they're raising.

EDWARD STEINFELD: You've presented a very sophisticated complex notion of what a sphere of influence is, but I think a cruder notion is its great power is carving up the world with each other, either fighting with each other or agreeing with each other to carve up the world.

But I think either within your notion or in addition to it, there's some kind of idea of a rule-based order, a norms-based order something that I don't know what the right historical analogy is that the Concert of Europe, the age of Mednick. But what's the what's the alternative to the crude form of spheres of influence thinking?

of Europe. That was agreed in:And the lesson of that is pretty clear. If you include all the great powers, if you get buy in from everyone who has the potential, the capability to overthrow the order you're constructing, you have a good chance of managing a peaceful environment for everyone.

If you do what we did after World War 1, which was vindictively to exclude Germany and then the newly formed Soviet Union, which of course, didn't really want to be part of the order. So it was not entirely our fault. So we excluded them from the European order and the result was World War 2 and the Cold War.

So I think yes after the end of the Cold War with regard to NATO, there was a proposal, I was involved in formulating and making it, for something called the partnership for peace.

And this was in essence a cooperative security mechanism, not a collective security mechanism. It wasn't aimed at any enemy. It was a way of managing the issues of war and peace in Europe.

I think NATO decided to go a different way. It went instead of building on the partnership for peace or transforming itself into an instrument of cooperative security, it succumbed to the Russophobia of Eastern Europeans, very natural. Bad experiences with successive Russian governments. And also to the Russophobia of the ethnic diasporas in the United States.

So basically NATO was expanded largely for domestic political reasons here in the United States without much thought of what it might mean to agree to go to nuclear war over North Macedonia, the latest NATO member whom I suspect very few can find on a map. So there are alternatives.

International law was the United Nations charter, a whole series of international conventions, the Geneva Conventions for example, which we set aside to create Guantanamo and other monstrosities. But the rules-based order is we make the rules and we decide which ones will follow but you follow them all or else.

EDWARD STEINFELD: Chas, I just want to finish with a question related to that. Do you think that China today has a global ambition for a Chinese sphere of influence? Or alternatively, can China be part of a rule-based order either regionally or globally?

CHAS FREEMAN: Well, I think with regard to the latter formulation, the answer is clearly yes. China is strongly committed to the underpinnings of the UN Charter and repeatedly asserts that and does seem to follow the rules of the UN Charter.

What it doesn't do is follow the rules-based order that we have proclaimed. Quite the contrary in fact, it objects to American unilateralism as do, the Russians and Indians and many others which is one of the reasons that a good number of countries beyond Western Europe, Japan, and South Korea are sitting this US-Russia struggle over Ukraine out.

So yes, I think the Chinese very much could be part of and were and are part of the international order that we helped devise after World War 2. That is clear.

Does China aspire to assume our role as the global hegemon? I don't think so. I don't see any evidence of it. I think the Chinese have a number of endearing characteristics, one of which is that they don't give a fig how foreigners govern ourselves.

So they're not trying to impose their ideology as we are. We have a Democratic ideology. We insist everyone must be Democratic or else. They just are indifferent apparently to this ideological question.

I don't see a reason that the Chinese would want to do anything except defend their own integrity as a country. And in fact, it's often said that they don't want to make the world unsafe for democracy. They want to make the world safe for their own autocracy.

So I think there is the basis for peaceful coexistence and more than that, cooperation across ideological and national interest lines. And I think we better find that basis because there are a series of planet wide problems, climate change, nonproliferation, the organization of a prosperous world in under agreed rules of trade and investment.

A whole series of issues. Pandemic management. We're going to have more of those. So we need to cooperate and I think we should make much more effort to do that than we are currently.

EDWARD STEINFELD: Chas Friedman, thank you so much for joining us on Trending Globally and providing really such an illuminating and provocative conversation as always. Thank you.

CHAS FREEMAN: It was my pleasure.

SARAH BALDWIN: This episode was produced by Dan Richards and Kate Dario. Our theme music is by Henry Bloomfield. Additional music by the Blue Dot Sessions. And if you haven't already, you can subscribe to Trending Globally wherever you listen to podcasts. We'll be back in two weeks. Thanks for listening.

[MUSIC PLAYING]