Shownotes

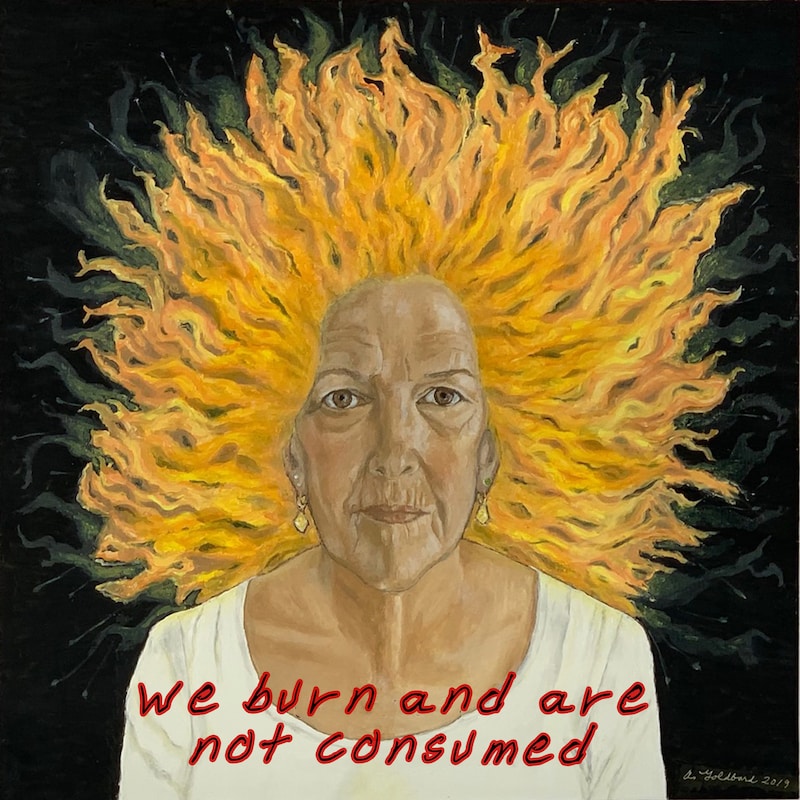

Arlene Goldbard

In this episode we talk to author, visual artist, educator, and activist Arlene Goldbard about her new book. In the Camp of Angels of Freedom: What Does it Mean to be Educated. In it she explores her life's journey along with a camp of 11 angels that include James Baldwin, Nina Simone, Paolo Freire, Doris Lessing, and Jane Jacobs.

Bio

Arlene Goldbard (www.arlenegoldbard.com) is a New Mexico-based writer, speaker, consultant, cultural activist, and visual artist whose focus is the intersection of culture, politics and spirituality. Her books include The Wave, The Culture of Possibility: Art, Artists & The Future; New Creative Community: The Art of Cultural Development, Community, Culture and Globalization, Crossroads: Reflections on the Politics of Culture, and Clarity. Her new book, In The Camp of Angels of Freedom: What Does It Mean to Be Educated? was published by New Village Press in January 2023. Her essays have been widely published. She has addressed academic and community audiences in the U.S. and Europe and provided advice to community-based organizations, independent media groups, institutions of higher education, and public and private funders and policymakers. Along with François Matarasso, she co-hosts “A Culture of Possibility,” a podcast produced by miaaw.net. From 2012 to 2019, she served as Chief Policy Wonk of the USDAC (usdac.us). From 2008-2019, she served as President of the Board of Directors of The Shalom Center.

Notable Mentions

Change the Story / Change the World: A Chronicle of art and community transformation across the globe.

Change the Story Collection: Many of our listeners have told us they would like to dig deeper into art and change stories that focus on specific issues, constituencies, or disciplines. Others have shared that they are using the podcast as a learning resource and would appreciate categories and cross-references for our stories. In response we have curated episode collections in 11 arenas: Justice Arts, Children and Youth, Racial Reckoning, Creative Climate Action, Cultural Organizing, Creative Community Leadership Development, Arts and Healing, Art of the Rural, Theater for Change, Music and Transformation, Change Media.

In the Camp of Angels of Freedom: What Does it Mean to be Educated: An autodidact explores issues of education itself through essays and personal portraits of the key minds who influenced her. What does it mean to be educated? Through her evocative paintings and narrative, author Arlene Goldbard has portrayed eleven people whose work most influenced her—what she calls a camp of angels.

Order this Book @: Arlene Goldbard.com and New Village Press

James Baldwin is considered one of America’s finest writers. He garnered acclaim for his work across several mediums, including essays, novels, plays, and poems. His first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, was published in 1953; decades later, Time magazine included the novel on its list of the 100 best English-language novels released from 1923 to 2005.[1] Baldwin's work fictionalizes fundamental personal questions and dilemmas amid complex social and psychological pressures. Themes of masculinity, sexuality, race, and class intertwine to create intricate narratives that run parallel with some of the major political movements toward social change in mid-twentieth century America, such as the civil rights movement and the gay liberation movement.

Nina Simone: was one of the most extraordinary artists of the twentieth century, an icon of American music. She was the consummate musical storyteller, a griot as she would come to learn, who used her remarkable talent to create a legacy of liberation, empowerment, passion, and love through a magnificent body of works.

Nina Simone @Monteau Jazz Festival (video)

Paul Goodman: was an American writer and public intellectual best known for his 1960s works of social criticism. Goodman was prolific across numerous literary genres and non-fiction topics, including the arts, civil rights, decentralization, democracy, education, media, politics, psychology, technology, urban planning, and war. As a humanist and self-styled man of letters, his works often addressed a common theme of the individual citizen's duties in the larger society, and the responsibility to exercise autonomy, act creatively, and realize one's own human nature.

US Department of Arts and Culture: The U.S. Department of Arts and Culture is a people-powered department—a grassroots action network inciting creativity and social imagination to shape a culture of empathy, equity, and belonging.

Dr. Ibram x. Kendi is a National Book Award-winning author of thirteen books for adults and children, including nine NewYork Times bestsellers—five of which were #1 NewYork Times bestsellers. Dr. Kendi is the Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities at Boston University, and the director of the BU Center for Antiracist Research. He is a contributing writer at The Atlantic and a CBS News racial justice contributor.

Golden Notebook: The Golden Notebook is a 1962 novel by the British writer Doris Lessing. Like her two books that followed, it enters the realm of what Margaret Drabble in The Oxford Companion to English Literature called Lessing's "inner space fiction";[citation needed] her work that explores mental and societal breakdown. The novel contains anti-war and anti-Stalinist messages, an extended analysis of communism and the Communist Party in England from the 1930s to the 1950s, and an examination of the budding sexual revolution and women's liberation movements.

Doris Lessing: was a British-Zimbabwean novelist. She was born to British parents in Iran, where she lived until 1925. Lessing was awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize in Literature. In awarding the prize, the Swedish Academy described her as "that epicist of the female experience, who with scepticism, fire and visionary power has subjected a divided civilisation to scrutiny".[2] Lessing was the oldest person ever to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, at age 87.[3][4][5]

Vaclav Havel: The unassuming man who taught, through plays and politics, how tyranny may be defied and overcome. Although a highly successful politician, four times head of state and the leader of one of the most famous revolutions in history, he was not a natural public figure. A sincere, impatient and humble man, he detested the pomposity, superficiality and phoney intimacy of politics.

Isaiah Berlin: Isaiah Berlin (1909–97) was a naturalised British philosopher, historian of ideas, political theorist, educator, public intellectual and moralist, and essayist. He was renowned for his conversational brilliance, his defence of liberalism and pluralism, his opposition to political extremism and intellectual fanaticism, and his accessible, coruscating writings on people and ideas.

Marjorie Taylor Green, Jewish space lasers,

Waiting for Godot: is a play by Samuel Beckett in which two characters, Vladimir (Didi) and Estragon (Gogo), engage in a variety of discussions and encounters while awaiting the titular Godot, who never arrives.[2] Waiting for Godot is Beckett's translation of his own original French-language play, En attendant Godot, and is subtitled (in English only) "a tragicomedy in two acts"

Waiting for Godot at San Quentin Prison 1988: This documentary was made during rehearsals for the play "Waiting for Godot," by Samuel Beckett, which was performed in 1988 by members of the San Quentin Drama Workshop at San Quentin maximum security prison, Marin County, California. Swedish director Jan Jonson directed

A Culture of Possibility. by Arlene Goldbard. "If we're going to end this fiscal madness and start rebuilding America, we're going to have to get creative! We need a tsunami of music, film, poetry and art. The Culture of Possibility shows us how creativity can take our story back from Corporation Nation, tilting the culture towards justice, equity, and innovation. I urge you to read this book!" Van Jones

Abraham Joshua Heschel (January 11, 1907 – December 23, 1972) was a Polish-American rabbi and one of the leading Jewish theologians and Jewish philosophers of the 20th century. Heschel, a professor of Jewish mysticism at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, authored a number of widely read books on Jewish philosophy and was a leader in the civil rights movement.[1][2]

National Guild for Community Arts Education: Founded in 1937, the National Guild for Community Arts Education is the sole national service organization for providers of community arts education. We believe in the power of the arts to transform lives. Our work helps realize that transformation every day.

The Higher Ground Community Arts of Spiritual Practice: This is the text of Arlene Goldbards’s keynote address at the annual conference of the National Guild of Community Schools of the Arts. It was delivered on 3 November 2006.

Liz Lerman: Hiking the Horizontal: Coreographer, education, and all around heritic-change agent Liz Lerman offers readers a gentle manifesto to bring a horizontal focus to bear on a hierarchical world. This is the perfect book for anyone curious about the possible role for art in politics, science, community, motherhood, and the media.

The National Conference on Religion and Race, held at Chicago's Edgewater Beach Hotel, 14–17 January...

Transcripts

Actually, I think she puts it better. She says, "our lives with all their miracles and wonders are merely a discontinuous string of incidents until we create the narrative that gives them meaning." In this episode, we talked to Arlene about her new book, In the Camp of Angels of Freedom: What Does it Mean to be Educated.

In it, she explores the question implied in the title through the story of her life in the company of 11, extraordinary, creative, intellectual, spiritual pathfinders, who she calls her angels. Our conversation meanders the tracks and trails of her journey under the influence of the likes of James Baldwin, Nina Simone, Paolo Freire, Doris Lessing, and Jane Jacobs.

Along the way, we encounter the tyranny of credentialism and false dichotomies, the evil of indifference and the power of an art fueled vision of possibility. It's a great trek. So onward!

This is Change the story, change the World, my name is Bill Cleveland.

Part One: Love and Listening.

Arlene Goldbard, welcome to Change the Story, Change the World. I'll just begin by saying I feel like your new book truly walks its talk, and I wanna thank you for the opportunity to join you on that walk on your odyssey of learning alongside your 11 angels. And if you don't mind, I'd like to jump right into some of those angel stories.

The first being Mr. James Baldwin, who I think we both agree, had very big wings. And the thing that felt particularly relevant for the time that we're in is this idea of seeing into the heart of the matter. We're having a hard time finding the heart, let alone seeing into it at this moment. And, if we could begin by just having you.

Quote, just one paragraph from this, and it's the final paragraph on page 17, and then maybe you could talk a little bit about Mr. Baldwin and his relationship to your journey.

[:The distance between personal and political disappears. He taught me that the little stories of our own lives always open into the big story crying to be told. No one is really fearless, but Baldwin seems so. Making plain the fierce love and desire that can overcome that are all that can overcome the wounds that goad us to retreat from vulnerability, from truth, from life.

[:Could you talk about what you learned from him?

[:He he got to the point where he couldn't stand to live in the United States with what was happening with white supremacy and the communities that he grew up in and was familiar with. But he kept coming to come back and be part of the freedom struggle because after he restored himself a little by his time in Europe or the different places that he lived, he filled up his tank and then it was full of love again.

In the book, I write about some of the ways it confuses me because people make very general statements about love nowadays. Facebook is five minutes a day social media for me, but I see a lot of statements where people say, I love black people, or I love my fellow Jews, or I love women, and I always get hung up and stuck on those statements because, I love some people who fit every category, and then there's some people I really have a hard time loving. I just can't quite stretch to the point where my heart will encompass them. And the thing he inspired me the most is to continue that struggle for my whole life, to try to love more, to try to love better, to try to love fully.

Still, I have a lot of questions about essentialism and categorical statements. I think the other thing as a writer, that touches me so much about his work is that there's no boundary between the personal and political. The story he tells of what he's experienced and the unique way that he, he perceives things, just slides seamlessly into the big story of the society and, it's discontents, and it's possibilities and I love that. It's so beautiful.

[:[00:06:57] AG: Yeah, in these, the chapters in my book, they're chronological, I jump back and forth a little bit, but the Nina Simone one I start, when I'm in high school, cuz that's when I became aware of through somebody who was another outsider, but from a very different place. My best friend at that time. And it so happened that her parents listened to the jazz station and went to concerts, and I got to hear some music that I would never have heard otherwise. And Nina Simone was right up there on, on top for me.

Did you ever see that essay that was written by Oliver Sacks, called the President's Speech in the New York Review a zillion years ago? He's sitting with these groups of people who were aphasics from strokes and things like that, watching Reagan give a speech and the people who could process the words but couldn't process body language, emotional coloration, just thought he was ridiculous and were laughing at the speech and the people who could process gesture and, and seeing, and so forth.

But not so much the linear language of the words, um, thought what a powerful presentation, . And I think there's a powerful lesson in, in that for all of us, because you have to pay attention to what people do as well as what they say, and whether it's music stories, accounts of other aspects of life.

There's very often, especially these days in the time of liars, a big contradiction between what is said and what is actually true, what is said, and what is actually done. So how do you perceive those things? You have to learn to listen to the language of your body. You and I, we both do a lot of facilitating and so we've both been in situations where you're getting this like nagging feeling in your tummy.

Something isn't sitting quite right here, and I don't know what it is. There's nothing linear and logical that you can point to, but you need to listen to the feeling to check out, am I having indigestion, or do these two people in the back of the room hate each other? And this is just about to blast off into a giant brouhaha for the group.

The thing about Nina Simone, if you see any of her concert films, and there's just a ton of them on YouTube and some really good documentaries about her too, is that every system, every neurological, every emotional, every spiritual, and every cognitive system that makes you a person, the volume was turned all the way up and she was completely alive in all those dimensions at any moment.

And so you would, you see these scenes in these concerts where she's making beautiful music and she stops in the middle because something is going on in the audience that's making her feel like she's not being received in the way that I think is Nina Simone's meta messages as an artist is everyone deserves to be fully received and to have that opportunity to show up in full presence.

And you see these moments in her concert films where that's not happening and she stops and she talks to folks and she tells them how she wants them to be listening.

[:[00:10:11] Nina Simone: Okay, we leave you with this and um, it's sad, but that's what you expected. Anyway,

Stars, they come and go.

They come fast, they come slow.

They go like, last light of the sun. All in a blaze.

Hey girl. Sit down!

Sit down,

sit down… (applause)

Stars they come and go.

They come fast, they come slow,

they go like the last light of the sun, all in a blaze,

all we see is glory.

[:[00:11:25] BC: I'm gonna put a sidebar in here cuz it reminded me of something walking into a room and knowing that there's something not right. That was a gift from my parents because, often I would walk into the room where they were and I knew something wasn't right. And you know, my radar told me that something really bad could happen and, and that I needed to make things cool. That came in handy in my work. So I really identify with what you just described.

[:[00:12:25] BC: Part Two: Citizens Who Don't Look Away

So, your chapter about Paul Goodman identifies him as the angel of the uncolonized mind holding the quality of self authorization. In it, you describe Goodman as quote, "the embodiment of the uncolonized mind. One truly free of cant, and ideology always questioning, imagining, and discovering without barriers." And then you go on to say, That "Goodman epitomized the right to be self authorizing as a citizen of a society or of the world."

From my reading, these ideas of decolonizing and self authorizing are core principles resonating throughout the book, but more as lifelong practice or struggle than an absolute destination. This, I think, ties in with your description of cultural citizenship as essential to the struggle for freedom everywhere. You say in the Goodman chapter that cultural citizenship requires no passport.

So, my question is, what does cultural citizenship require? What will it take for a nation of society, a community to embrace and celebrate this notion of each human having an inviolate cultural presence that establishes their right to self authorize as a global citizen?

[:And you and I have seen this countless times that even in a room full of people where you may have an assumption of some sort of entitlement that many of them feel based on outward cultural characteristics or whatever. You're gonna get half, two thirds, maybe three quarters, depending on who's in the room ---everyone who's feel like, "I'm not a real American," or "I don't really belong here", or "I never really felt at home in the place I came up." Now other people are rooted and more power to them. I'm not saying that's a totalizing statement, but say for somebody like me, whose family was only in a country for one generation or two generations before, they were forced to move on to another place.

I'm not connected any sense of land. I love my land that I live on, but I can't say, I mean, look at the rise of anti-Semitism in America right now, that there's not gonna be a reason five years down the road where I'm going to pick up and move to, you know, a, a far away land. So it's not about that kind of geography, but the inner-geography of belonging.

So, you know, in the condition of cultural citizenship, and I mean true cultural citizenship, which needs no papers, we all feel at home in the place where we live. All of our contributions to having created that place are recognized as essential and equally important as everyone else's contributions. There's not a hierarchy of the rich, white founding fathers who are really responsible for this place, and then everyone else came along and worked for them, and they don't really have much to say about who we are.

So, it's that feeling of deep equity and equality, that deep participation, and I think something very important that often gets left out, which is an equally deep curiosity and friendliness with which we greet each other. I wanna know who you are. I wanna know more about you. I don't want, Bill Cleveland is a middle-aged white man to, I don't wanna pretend that tells me something about who you really are, what your story is, and what you might have to offer. So, I would say whether it's on the level of an individual, a family, or a community, those fundamental values and principles--- We're all welcome.

We're all curious. We're all friendly, or at least aspiring to be. These things and all of our contributions are recognized. That has to be foundational. When I was doing the USDAC (United States Department of Arts & Culture) thing, I created a policy that could be adopted by an organization or a government agency that could assess the level of belonging that's reflected in the policies and laws, regulations, programs that they promulgate.

I'd love to think every, every institution, and every community could adopt a policy like that, where in addition to looking at, say, economic impact, or environmental impact, they look at cultural impact, and that it's called the Cultural impact study or Cultural Impact Policy. Haven't got anybody to pick up on it yet, though, Bill.

[:Which brings me to Doris Lessing. Um, one of the things you identified as important in your relationship with her was not looking away, seeing and feeling and embracing the good and the bad. Here's a quote from you. "I learned how easily people live inside a political culture that commands them to look away."

So my question to you, is there something about art making or cultural practice that can mitigate the looking away, that makes the hard learning story more enticing and the denial story less avoidable?

[:And I talk about how I succumbed to some of that as a person of the left in, in, in my earlier life of just knee jerk. These are my friends, these are my enemies. These people can't have anything to say that would possibly be useful or relevant to me. And I have to agree with everything that these other people say cuz they're on my side.

And when I was freed from that, it was such a relief. It was like the top of my head opened up and air could come into the places that were clouded. So as a story in the Golden Notebook, which is the first book of Doris Lessing's that I read back in the sixties, um, in which the main character is a member of the Communist Party in England, in London. And this is right before the 20th Party Congress that revealed the gulags and, and all of that.

And so, there were many more people on the left apologizing for things that were hinted about that the Soviet Union was doing, but hadn't actually become known outside yet, and hadn't yet triggered a big exodus from the Communist Party, which is what happened when they did become known. And she's at this meeting of an editorial board of a little journal and somebody submits an article and all the people around the table are considering it.

And it tells a fantasy. And the fantasy is that this guy's a worker and he goes to Moscow for a Party Congress and he's wandering around and he just walks through a door and there's Stalin sitting at his desk smoking a pipe late at night, and Stalin welcomes him and he sits down, and they have a long conversation about the problems of workers in Britain.

And he goes home and feels wonderful and. The people on the editorial board are embarrassed to say what they really feel about the article. Which is that it is just like one they got last week where Stalin fixed this tractor for these two guys, and it's just like another one where he put a bandaid on the cut.

You know, father, father Joseph basically took care of everyone. And in the way that Lessing depicts it in the book, you see the, all the truths of it. You know, why they're holding to the lie. And I write much later about Vaclav Havel writing about living within the lie or living within the truth. And that that comes out in another dimension.

And I think all, we've all done it, I, I definitely think the right is doing it now. And I think virtually all of we progressives have done it too. You know, been in that situation where we looked away because someone told us that was the right thing to do and we decided we had to conform and

[:Part Three: Higher Ground.

So I'm gonna go forward to Paolo Freire. Your title of this, Critical Consciousness: Holding the Quality of Self-Determination.

And there's actually something here I'd like you to read. It's on page 50 and it's, it starts with, "there has barely been a day in the intervening decades."

[:"There's barely been a day in the intervening decades that Ferry's wisdom hasn't offered me a key to understanding power dynamics in organizations, but equally in family patterns, in national and international politics, in the relations of race and gender and sexuality, of social exclusion and inclusion reflected in every cultural manifestation. The context may be an actual family in which grown children endow their father with power, such that they constantly seek approval at the cost of suppressing their own gifts and desires. Or it may be vast, the epidemic of magical thinking that persuaded millions of voters to believe that a mendacious millionaire reality show host could ordain white supremacy forever."

[:"No doubt politics are easier if you know who the great Satan is, but sacrificing the ability to see the world in all its contradictions and complexities seems a high price to pay for ease."

And my question to you once again is, do you see a role for the art makers of the world for helping dispel the illusion of the black and white easy answer view of the world?

[:And of course, the way our minds work, we need to craft a narrative or a conclusion out of this vast amount of data that's coming into our senses and our intellect at all times. So we're gonna make a story out of it, and maybe that story will be a song or a play or a painting, a mural, or a photography project, or all the things that, that you and I help people work on all the time.

But the fact is, the more truth that's in it, the more people will recognize, or awaken to the reality that they've been experiencing, but may be somehow truncating or occluding or just resisting out of force of habit of having adopted a certain ideological position or whatever to see everything that's really there.

You know, it's a tough thing, Bill, because look at politics in this country right now. I mean, electoral politics, so polarized beyond polarization. And some of the things that people on the right believe, declaim all the time, are so patently ridiculous and untrue that it's hard to have respect for the speakers or even to care enough to wanna figure out why they might be feeling that way.

Marjorie Taylor Green, "Jewish space lasers," really, some of these people are fucking nuts. But the fact is, if we don't interrogate what's happening by letting all the information be before us, and looking for a way to understand it without erasing half of it, I don't think there's any way forward outta that.

I don't think it's a kumbaya moment where we all sit down and chat and agree on something. You know, I don't do as much consulting as I used to. Back when I did it, I used to always start with an organization by talking to folks there individually, confidentially, to find out the landscape. And, very often you'd be in a situation where two people would be in conflict with each other, and that would be affecting the organization as a whole.

And I would say, "Why do you think he said that to you? or "Why do you think he did that?" And the prison I was talking to would say, "I don't know." And I would probe ,and reprobe, and re reprobe to try to get them to just imagine any reason at all why the other person was behaving as they did. And the resistance to imagining that was often pretty profound because, once you let in the idea that everybody has their reasons, then you have to see that other person is human. They can't just be your enemy. You have something to work out that's not so easy, but a door is open.

So, isn't this what art does? You know, isn't this what the best art does? Isn't this what the art that really reflects the true complexity of people's lives does. And that's one of the reason why I've always been so attracted to community-based art and community-based artists because whatever depiction, in whatever form, whatever creation is the result of their work, the process of getting there is allowing many voices to be heard and contend simultaneously without disrespecting any of those voices.

And that's what produces that vision of possibility, and that's what produces the chance that you or I might care about why somebody did something else. And, that caring might be a path to understanding, and that understanding, God willing, could be a path to change.

[:" survive here by imagining these people as not people, and every moment of what they're doing in that classroom gives lie to that. You know, my worldview is shattered by being involved in this, and I'm going home weeping. My wife thinks I'm crazy. I could lose my job if I don't behave in a particular way"

[:[00:29:47] BC: Now, that was imprisoned actor Twin James from the final scene of our 1988 San Quentin production of, Waiting for Godot. Now, the good news about that struggling correctional officer is that he did come back and he did reconcile, but there were many who basically said, "I can't handle this. I'm a cattle herder here. I can't handle herding people." So it's a powerful thing.

Something else about Berlin, that you talked about is the concepts of clear and dark layers and what we see in what we don't see in intimacy. Could you talk about how that relates to cultural community work?

[:I wrote about it in my book, A Culture of Possibility. I called it Datastan, a Society in which only what can be weighed, measured or counted counts and everything else is just push it off to the side has gotten us into many of the predicaments that we're living through right now because the human subject can't be portrayed by data.

You know, it, it's impossible to reduce you or me or anybody else, to a set of like tests and numbers and columns and graphs and Berlin asked this question, "Who do you think would be more likely to predict accurately a, an individual's response to something? A data scientist who just knew everything that could be quantified about that individual ,or a friend, someone close who knew that person very well.

And of course, we all know the answer. There's no way that a machine essentially can understand us better than our own hearts and minds and spirits can understand each other. And that again, is the essence of art making that there, there are some people who make art that could be made by a machine. We're seeing quite a bit of it now.

[:[00:31:48] AG: But in this collaborative community-based practice that we're talking about, of course, that's not the intention and that's not the execution. You know, I, I often use as a shorthand, these four words that sum up a, an a core idea of Jewish spirituality, which is that we live simultaneously in physical, emotional, intellectual, and spiritual dimensions.

And the work that we're talking about, Exists simultaneously in all of those dimensions, believes that spiritual information and emotional information and physical information are just as important as intellectual information and tries to imbue the work that people are doing with all of those dimensions so that it really resonates fully with what it means to be a human subject.

[:[00:33:34] AG: I can't now remember what year this must have been, but it must have been the late nineties. I definitely had a spiritual experience. I was very demoralized in my life and I read a book about Jewish spirituality that suggested that the things that we're experiencing as obstacles and punishments may just be preparation for the specific role that is ours to play in our lives.

And what Heschel says is "some, something is asked of you, but we don't know when it's going to be asked or what is going to be asked. And so we need as much as possible to maintain ourself in a state of readiness." I'm not religious in, uh, conventional sense, but I'm very involved in spiritual study and practice.

And on this particular occasion, I was invited to give a keynote address. It's now it's called, I think the National Alliance for Community Arts Education. I forget, but it was community music ed education back in those days. And the guy who started it actually in the first place, his backstory is that he started a clandestine orchestra in the Dachau concentration camp.

So, I already knew when they invited me to do this keynote for their conference that there were, there were some interesting convergences and I knew I wanted to talk about the kind of work that you and I have been describing as we've had this conversation so far as a form of spiritual practice in addition to whatever else it is.

Oh, it's making, it's doing is this and that, but it's also a form of spiritual practice in the sense that we who make the work together are sort of the most God-like when we're doing it. We're letting in all of those dimensions, we're creating the world that we would like to see exist. We're entering into a kind of communion with each other.

So I decided I would write a talk. It's on my website. It's a, which is arlene goldbar.com. It's called The Higher Ground Community Arts of Spiritual Practice. And Heschel's concept of radical amazement was a really formative one for me there. I love the way he expresses it.

He says that no matter how much science can tell us about how the world works, it will never tell us about why it exists and that our true condition as human beings is in a state of perpetual wonder. Here we are in this giant rock spinning through space . We have no idea why or you know, what's to come or anything. And if we stay in that condition of amazement and wonder, then we're open to all input. As you and I have been discussing, then questions are not enemies. They perpetually arise and engage and flow and, and move on that when we do the work well, we're helping other people to enter into that condition of radical amazement.

So I, you know, I'm shaking like a leaf. I get up on the dais, I give my talk, and everybody started crying. And that touched my heart so much, and I realized that they were crying because they heard out loud a story that they may not have articulated in words to themselves, but that lived as a little kernel, or a seed inside their own consciousness, inside their own way of being that they didn't think they were just doing a job.

They also thought they were doing this big spiritual engagement. They also thought they were healing the world by what they were doing. But mostly in the world they lived in data san to reference that again. Nobody was asking how they felt about that. Those questions were not on the table. The table were how many artist/client contact hours did you have, and circle from one to five whether he gained in, in, in this kind of skill or other.

So I realized that the tears were because. I was telling the real story as they lived it and that was what, that was a high point.

[:That's not what it is. And once you enter into that world, the moral and ethical dimensions of the work, take front stage, because you're in a transformational practice. You can make mistakes with other humans when you mess with their lives using this power, and you need to be careful and conscious and respectful.

Could you say more about what impelled you to broach that subject that I'm actually pretty sure most art schools aren't running around looking for that workshop.

[:And two things are true. Three things are true. One is you're absolutely right. It deserves at least a full course, right? The ethics of the work. I'd never seen a semester long course in any higher education institution on ethics, so that sucks. And whenever I do it, it's the first time and I've probably done it a hundred times in different contexts. No one's ever been in, in a conversation like that before, except a private conversation with it. "Oh, I have a problem. Let's talk about."

Two things that are most important to me to impart are that ethical challenges will always arise in any collaborative work with human beings. It's inevitable. There's no way out of it. And that the default setting that many people are taught to have, which is,

"I don't wanna make a mistake. I, I have that feeling in my tummy, but I'm just gonna ignore it and hope it, it will go away," is a losing strategy.

And so, I wanna encourage people to develop and sharpen their ability to sense ethical dimensions of the work and to bring them forward, to have productive ways to work on them with the group and to accept that they'll always happen. And it's not a failure if somebody censors you, for example, which is one of, one of the most common.

And the other thing that I am trying to impart in, in doing that work with people. How many sides there are to a story, not in terms of a moral equivalency, that they're all equal and they're all right because sometimes power throws its weight around. There isn't a "both sides-ism" aspect, you know, that you can work out.

But in many situations, for example, just because censorship happens so often, that's probably the classic frame that people pick when they give me stories about their work and what could I have done and what could happen. The group brainstorms with them using a set of questions that that I suggest to them, and the questions are designed.

To first get your own sense of what's happening out of the way, and then to put your feelings about who's right and who's wrong. Cuz all of our knees jerk and they jerk In every situation like that, put those things aside. Then we look at it as if we were martians just arriving. You know what's really happening here from all the different perspectives.

I ask people in the group to take on the first person roles of different actors in whatever's happening and that circle of actors keeps getting widened. So it might not be just the folks who worked on the mural, and the people who on the wall, and the funder who said, I don't like what you depicted there. But, it might be the people who live in the neighborhood and the parents of the kids who worked on the project, and the people who understand the history that's being depicted in the mural.

And you go out, and out, and everyone has something to say. And often what people have to say as I imaginatively inhabit these multiple roles in relation to whatever the ethical challenge is, not what you think of right off the top of your head when somebody tells you the story. So that's the third thing that I wanna impart by doing that work with people.

And here we are, you and I Bill, were singing the same song over and over again here, which is, there's just more to reality than there appears to be on the surface. And it, the more you know about what everybody is feeling ,and thinking ,and doing in relation to this, the more able, skillful, and adept you'll be at learning something from it and finding a way to go forward.

[:Part Four: The Squandered Power of Lived Knowledge.

So, your book has two parts. You have these incredible portraits, both in words and images of your 11 angels, but as you say, in the second half, you have an agenda that's attached to this. And if you could just briefly talk about credentialism and the auto club.

[:But going forward, there's all these high tech people, there's all these amazing artists, household names who just didn't take that route and aren't usually recognized for sometimes, the unique qualities that I described, when we talked about Paul Goodman as the decolonized mind --- the ability to forge one's own path without being over much concerned with what other people tell you the right thing is to do.

So, it's funny cuz I speculate in the book like, "Why do I care so much about this?" Cuz I care about it so much and, I'm not gonna make some kind of claim that it's the worst problem in the world, but credentialism is a bad problem getting worse and worse, and there's lots of examples of how it manifests.

So, for example, we're all reading now about these elite higher education institutions, Harvard, Yale, Princeton, places like that. Massive tuition charges, massive endowments. These places have multi-billion dollar endowments that they're just sitting on and profiting by and not spending. , keeping the admissions small so that the value of the diploma from that institution keeps getting inflated, inflated, inflated.

And by everything that they do, generally broadcasting the impression that higher education institutions are the citadel of knowledge, that they're the only legitimate path to learning. And that if people haven't followed that path, they might be very nice people, but they really don't have anything to offer the society. It's something that breaks my heart and makes me very angry, and people keep asking me, how have you been hurt by it? And the truth of the matter is not at all. My story is not one of being held back by not having a college degree.

I'm smart. I worked hard. People asked me to do things. I'm just really not handicapped at all by this. But, because I'm not, and because I came up the way that I came up and can see, as a result of what my childhood was like, my family history, and also my life experience, I'm just surrounded every day by people who are severely harmed by it.

So, people who do ordinary jobs, you know. I ask in that section of the book ---somebody fixes your plumbing, somebody who waits on you at lunch, do you think of them as having the life of the mind? Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was a bartender for years and years before she became a candidate, and imagine how insulted she was in so many situations by people who thought that meant that she had no intelligence and nothing to offer.

I want to break the grip of the assumptions that underpin credentialism; this valuing of credentialed expertise over liveed knowledge, and the consequent devaluing of the individuals whose path to wisdom has been through lived knowledge. I wanna break the grip of that on people's minds.

And in part two of the book, I just tell a lot of stories that I think illustrate how powerful that grip is, including like sitting around at dinner with my friends after Trump is elected and you know, everyone at the table is saying, I blame the schools. Which is, the schools are pretty messed up right now, but that's a ridiculous point because there are just about as many right wing PhD's as there are left wing ones. You know, all the folks in Trump's administration and the ideologues who support, have prestige blue ribbon degrees from very expensive higher education institutions.

But there's this idea that's infiltrated the society that says that you have to pass "GO," be credentialed in this way, represent the values of these institutions, support their entitlement to be the sole source of legitimate knowledge to get along in the society. And if you don't do that, you won't amount to anything.

I wanna change that. I know so many people who've learned in other ways, and have so much to offer, and have been incredibly accomplished. And, I only think of all the ones who haven't had the little hand up, or the little chance, or the little room and openness in the society to show that they can do the same.

[:And certainly the credential thing is obviously one of those simple rules. Which is, have hegemony over one of the most important power centers, and then you create a rubric that basically separates the wheat from the chaft. In the book, you share a strategy that you think could be applied to post secondary education, that might help open the gates and help expand the conversation about, you know, critical issues we face.

Could you talk about that?

[:And you know, I talk about how there's this feeling of we'll just get back to normal and we'll do everything exactly like we did it before, but there I offer a way that these institutions could truly become relevant by offering a space for study and reflection and so forth to look at our shared situation and say we're in a pickle.

What are we gonna do about it? We have a lot of smart people inside this institution. Let's open the gates to the people outside the institution. Use the methods of community arts work that, that you and I are talking about; where everybody has a story to tell and they're all welcome, and they're all brought into the conversation, and use the kind of creative cultural research methods that people use in our work to devise some scenarios for how to go forward and then to work with individual students about where do you see yourself in this scenario? Is there a place for you here? How can you be effective in this scenario? These are the questions that seem to me the ones worth asking right now.

How shall we live? And maybe I'm not seeing it, but I'm not seeing it.

[:As Liz Lerman describes it in her book, Hiking the Horizontal, we are addicted to a vertical mode of thinking, you know, that assigns a hierarchy of value and meaning to a limited range of people, and histories, and ideas, which automatically places us in the realm of scarcity. Here's how Liz put it in her introduction to the audio version of her book:

[:It's more like a seesaw, and that is why dancing and art making provides sustenance for the hike ahead. If we are lucky enough, we can actually take the long highway between the sometimes opposing forces.

[:No, of course not. But it does mean that the threshold, moral and ethical discussions that these powerful inventions, these forces engender should involve the people and communities who will ultimately bear the consequences of their successes and failures. Overreach. So would that be easy? God, no! When I, when I engage gatekeepers with these kinds of questions, they immediately focus on this messiness.

Yes. Actually, including other people's voices is hard. Looking people in the eye, and listening, and taking them into account is super hard. Democracy's hard. But the consequences of not doing that, of not listening, and learning, and acting together is harder. And we're paying the price right now for this.

And, you know, given that paying attention is the heart of creative practice, it's not surprising to me that the cultural workers that you and I work with seem to be the most insistent about this kind of listening and accountability.

Arlene, there's a place at the end of the book where you engage your angels in conversations. And I have to say, I'm really glad you did that because I sensed them wanting to have the floor, uh, throughout the book, you know, to speak out. Anyway, there's a moment where Heschel speaks to the other angels about the evil of indifference that I think is relevant to this idea of listening and taking everyone's story seriously.

Could you read that? It starts with the last time we talked...

[:So they've had that conversation already. And then, Abraham Joshua Heschel, whose, whose name you heard before about radical amazement, speaks up, talks to his fellow angels.

Last time we talked, we granted permission to quote yourself. Heschel looked around, seeing no objections. You are reminding me of something I wrote, and then he quotes it. There is an evil, which most of us condone and are even guilty of indifference to evil. We remain neutral, impartial, and not easily moved by the wrongs done unto other people. Indifference to evil is more insidious than evil itself. It is more universal, more contagious, more dangerous, a silent justification. It makes possible an evil erupting as an exception, becoming the rule and being in turn accepted.

That's the end of the quote. And then he goes on;

rence on Race and Religion in:Heschel and King became really close friends toward the end of King's life and um, actually Heschel had invited Dr. King to the first Passover Seder that he would have ever been going to in April of 68. And, Dr. King was killed before he could go to that. So there's a really strong bond, and I have a picture of above my desk of Dr. King and all the civil rights leaders marching in Birmingham. And Heschel said of that, "When I marched in this situation, I felt my feet were praying."

[:And I asked her, I said, "So, could you just talk to me about the strategies and processes that you use? that makes this work have integrity. Where does the integrity come from?" She looked at me and she ripped me a new one. She said, "This work cannot be techniqued. I am not going to talk about technique. This is a work of heart and spirit. That's always changing. What seems true today? Can be false tomorrow. Don't be convincing yourself that you. Always know the score can sit on the sidelines. That's why you have to stay vigilant. And stay engaged.

And I have never forgotten about that. And today, we live in a world dominated by bullet points. Everybody seems to want the quick and the clean. And with this book, I think you've ended up making something that transcends that. And one of the great things you do at the end is you invite readers to call up their own angels as a landing spot for the odyssey of this book, which again, walks the talk and epitomizes what I think are the high standards for this kind of art and community work, which is at the end of the day, you know, the simple message.

This story is about us. And if we take you up on your suggestion, our angels.

[:I think for most people I know doing that would also enlarge their personal sense of what valid knowledge is and their personal sense of how it's acquired. So, suggesting that people encounter their angels was also a way of suggesting that what I'm trying to impart in the book can be learned experientially through scrutinizing your own past your own thoughts and feelings.

[:And Arlene, thanks for the gift of your work, this fabulous book, and for sharing it with us. Really appreciate it. Thank you. Thank you, and thanks listeners again for tuning in.

If you're interested in grabbing a copy of Arlene's new book, you can find it at New Village Press and at Arlene's website; links to which we will be sharing in our show notes.

On a personal note, I'd like to let you know that after a couple of years here, blathering away, we're happy to say that we. A pretty solid audience, which is both gratifying and encouraging. So much so that we're keen to expand it.

So if you'd like to help us do that, there are a few things that you might do. First, please share the show regularly with your community, and subscribe if you haven't already. Next, if you have any ideas about how we might connect with fellow travelers out there, you know, newsletters, mailing list, local arts organization that might wanna embed a podcast that showcases changemaking artists on their website, let us know at csac@artandcommunity.com

"artandcommunity" is all one word and all spelled out. Also, if you have ideas for guests or improvement to what we're up to here, drop us a line. We'd be grateful.

Change the story. Change the World is a production of the Center for the Study of Art and Community. Our soundscape and theme are a miraculous manifestation of the extraordinary musical imagination of Judy Munson.

Our text editing is by Andre Nnebe, our special effects come from freesound.org, and our inspiration as always, comes from the mysterious and ever present spirit of UKE 235. Until next time, stay well do good and spread the good word.