Shownotes

Àmọ̀kẹ́ Kubat's work rises up in a dozen different overlapping directions. In North Minneapolis you'll likely hear her described as an organizer, a puppeteer, a healer, a priestess, a playwright, a counselor, a writer, a teacher, an actress, a curator, a storyteller, and more often than not, a provocateur.

Bio:

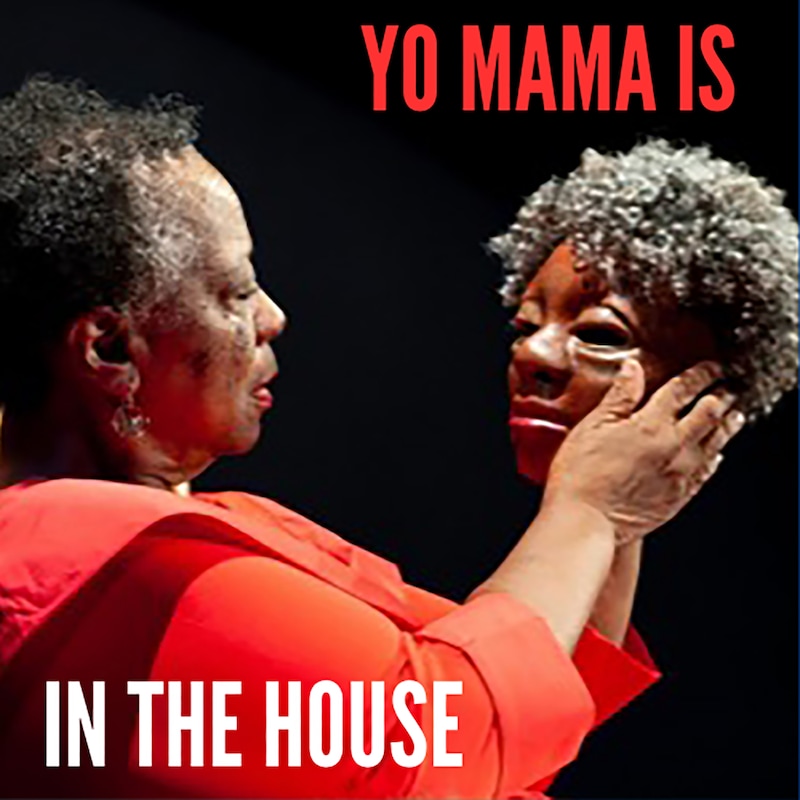

Amoke Kubat is an artist, weaver, sacred doll maker, and sometimes stand-up comedian, who uses her art to speak truth to power and hold a position of wellness in an America sick with inequality and inequity. In 2010, Amoke began developing her Art of Mothering workshops, which became the foundation of Yo Mama’s House: a cooperative for women who are artists, mothers, activists, and healers in North Minneapolis. Amoke used her residency to support the development of Yo Mama’s House by building relationships with researchers of African history, race studies, and other fields that might inform her work to reclaim Indigenous African sensibilities.

Notable Mentions:

Creative Community Leadership Institute (CCLI) Established in 2002 CCLI was a community arts leadership development training program developed by Intermedia Arts in Minneapolis, MN. Over its 22 year history the program supported a network of creative change agents who continue to use arts and culture to help build caring, capable, and sustainable communities. When Intermedia closed its doors in 2017 the program was suspended. The program re-emerged in 2021 under the auspices of Springboard for the Arts in St. Paul Minnesota, and Racing Magpie in Rapid City, South Dakota. The program supports the development of strong leaders capable of challenging and disrupting oppressive systems in their communities by approaching their work with a critical lens and commitment to recognizing systems of oppression and normalizing conversations about race and colonialism. CCLI serves Minnesota, South Dakota and North Dakota artists.

North Minneapolis: Northside is one of Minneapolis’ most diverse neighborhood areas. Prince spent a few important formative, guitar-strumming, piano-tapping years in the area. The local businesses, events and entrepreneurs are bringing a new life and energy to the area with a focus on community-led growth. These changes include a thriving cultural presence, often seen through food and artistic expression.

Paul Wellstone: (July 21, 1944 – October 25, 2002) was an American academic, author, and politician who represented Minnesota in the United States Senate from 1991 until he was killed in a plane crash near Eveleth, Minnesota, in 2002. Over the years, Wellstone worked with senators whose views were much more conservative than his, but he consistently championed the interests of the poor, the farmers, and the union workers against large banks, agribusiness, and multinational corporations.

Yo Mama's House: Mission: Our philosophy and practice is to empower mothers by disrupting the devaluation of women’s invisible labor and increasing the recognition of the ART of Mothering. It is MOTHERS’ collective legacies of maternal wisdom and know how that informs, nurtures, and sustains women. Healthy mothers raise healthy children, families and communities. Arts

Walker Arts Center: From the Walker Webpage: The Walker Art Center is a renowned multidisciplinary arts institution that presents, collects, and supports the creation of groundbreaking work across the visual and performing arts, moving image, and design. Guided by the belief that art has the power to bring joy and solace and the ability to unite people through dialogue and shared experiences, the Walker engages communities through a dynamic array of exhibitions, performances, events, and initiatives.

Sick and Tired of Being Sick and Tired Rocking Chair,

Kulture Klub Collaborative: The mission of Kulture Klub Collaborative (KKC) is to provide a safe, consistent space for youth ages 16-24 experiencing homelessness to freely enjoy access to the arts. At KKC, we believe that everyone is an artist. We expose, educate, and empower youth through quality multidisciplinary art experiences. We use art and creativity as a positive force in their lives for personal growth, social justice, actionable compassion, and community improvement. Mama

Center for Cultural Innovations, Ambitious Fund: AmbitioUS is an initiative of the Center for Cultural Innovation (CCI) encouraging the development of burgeoning alternative economies and fresh social contracts in ways that artists and cultural communities can achieve financial freedom. Art Center at the University of Minnesota.

Angry Black Woman and Well-intentioned White Girl. Angry Black Woman & Well-Intentioned White Girl explores the cultural impact surrounding “Minnesota Nice” and the misunderstanding it can cause in interracial interactions. This play “Goes there!” by expressing the daily “unsaids” between black and white women.The accusations and silences reflect our miseducation about each other - the superficial and deep conflicts around our womanhood, ethnicities, rights, power, and constant juxtaposition of roles within the politics of white male patriarchy.

Minnesota Nice: While there's no official definition, the term typically refers to Minnesotans' tendency to be polite and friendly, yet emotionally reserved; our penchant for self-deprecation and unwillingness to draw attention to ourselves; and, most controversially, our maddening habit of substituting passive-aggressiveness for direct confrontation. Cities Detoxifying Masculinity

Yoruba, Ori: Ori is regarded as an intermediary between every man and the divinity whom he worships. Each individual’s Ori is his personal divinity who regulates his life in conformity with the wishes of the divinities who exist for the general public interest. Whatever has not been sanctioned by one’s Ori cannot be done by the divinities

Mr. Jamar Clark: Jamar Clark was 24 years old when he was killed by Minneapolis police on November 15, 2015. He was at a friend’s birthday party when his girlfriend got into an altercation that resulted in someone calling the paramedics and police. Jamar was near the ambulance as paramedics treated his girlfriend. An onlooker reported that for some unknown reason police asked Jamar to step away from the ambulance. A confrontation ensued between Jamar and two police officers, who attempted to detain him, forced him to the ground, and fatally shot him. Jamar was unarmed, and according to eyewitnesses, was not resisting arrest.

The officers were not disciplined by the department, and no charges were brought against them. Black Lives Matter (BLM) activists and supporters protested for 18 days outside the police precinct, protesting against hiding information, demanding the release of police dashcam and bodycam videos containing material evidence that can settle the truth of police accounts of the incident.

*******

Change the Story / Change the World is a podcast that chronicles the power of art and community transformation, providing a platform for activist artists to share their experiences and gain the skills and strategies they need to thrive as agents of social change.

Through compelling conversations with artist activists, artivists, and cultural organizers, the podcast explores how art and activism intersect to fuel cultural transformation and drive meaningful change. Guests discuss the challenges and triumphs of community arts, socially engaged art, and creative placemaking, offering insights into artist mentorship, building credibility, and communicating impact.

Episodes delve into the realities of artist isolation, burnout, and funding for artists, while celebrating the role of artists in residence and creative leadership in shaping a more just and inclusive world. Whether you’re an emerging or established artist for social justice, this podcast offers inspiration, practical advice, and a sense of solidarity in the journey toward art and social change.

Transcripts

From the center for the Study of Art and Community. This is Change the Story, Change the World. My name is Bill Cleveland. Now, more and more, we seem to be living in a world of overlaps.

I would posit that this has always been the case, but we've only just begun to acknowledge the permeable nature of the silos we've constructed to protect us from the daunting reality of that everything is pretty much connected to everything else.

Of course, I'm oversimplifying here, but I do find it interesting that when you look at the nearly 100 people we've talked to on this show, almost all of them are what I call hybrids, multi sector explorers who have spent their lives exploring that cross sector Venn diagram of a universe.

There they are, combining their creative skill sets with their interest in so many other realms like medicine, public safety, education, community development, transportation, aging, climate, justice, peacemaking. Well, the list goes on and on.

Now this show's guest, Amoke Kubot, is a prime example whose work as an early childhood educator has morphed and evolved in response to the opportunities and needs rising up from her community in a dozen different overlapping, interdependent directions.

Ask around the north Minneapolis community where she lives and you'll likely hear Moke described as an organizer, a puppeteer, a healer, a priestess, a playwright, a counselor, a writer, a teacher, an actress, a curator, a storyteller, and from time to time, a provocateur.

The irony, of course, is that Amoke is very label resistant and prefers to let the impact of her work in these realms not only speak for itself, but also tell her what's next. While I think Omoke would also describe herself as old school, I have always thought of her as way ahead of the curve.

And given the increasingly twisty nature of our world, I'm quite eager to learn more about how she has managed to successfully navigate her extraordinary journey. Part 1 Northsider for Life Omoke, Cuba, is from the north side of Minneapolis.

For people who are not familiar with the Twin Cities, North Minneapolis is not just a space at the top of the map. It's a distinct social and cultural destination with a history of struggle, resilience, and resistance.

I met her when she was a fellow at the Creative Community Leadership Institute in Minneapolis. Ccli, as it was called, was a network of community arts leaders I was working with in the Twin Cities.

Sharing that connection and context is important here because Amoke is very much a place based practitioner. By this I mean that where she sits and who she sits with constitutes the foundation of her life's work.

Speaker B:Right now I'm in the sacred and traditional homelands of the Dakota and the Anishnashbe people and. But I live in north Minneapolis. Yeah, my north sider for life. I came here from Los Angeles and said, where's the black people at?

Where's the poor folks? I wanted to be around people that I understood culturally, Shared experiences, struggles. I like people that.

Where the creativity and the resilience and the laughter and the. Even when people are desperate, they are still finding some purpose in life.

Sense of community tied to historical roots, tied to land, tied to storytelling, tied to migration. Black people are not colonists. We weren't refugees. We have a whole different label.

But we know land, we know earth, we know planets, we know connectivity.

Speaker A:Many from outside the state regard Minnesota as a liberal bastion, given the area's history as the home of democratic farm labor politics and progressive patron Saint Paul Wellstone.

stark, A fact brought home by: Speaker B: tually, north Minneapolis, in:And there's been a lot of practices put in place to keep people here in this area. But there's also another practice of pushing people out and displacing them and extracting the wealth. And somehow we're never.

If people do recognize the strengths and the talents, those are usually what people want to commodify and take away from us. Like, they bring in programs.

They want to get our above average students and then take them to a suburb someplace and say, yay, we're helping somebody. No, you're gutting the community. That bright mind needs to stay. That entrepreneur needs to stay here. That budding doctor needs, needs to stay here.

Like, my daughter had a really horrible time in Minneapolis public schools. She was very sad, and when she got into middle school, she became angry and defiant, and there was a lot of fighting.

So I would tell her, you need to take that mouth and become a lawyer or something. But you had to calm it down. She's one of the best community organizers going.

Speaker A:She is.

Speaker B:She's hell on fire. I always tell people she could run the devil out of hell.

Speaker A:Amoka Shuns labels In the same way, she avoids arguments about ideologies and theories and affiliations.

And as I said before, she's a hybrid soul with many layers and stories on a life path that combines teaching and creating, all with an insatiable drive to tell the story like it is and with her neighbors, change the story like they want it to be. She also describes herself as a doer, and from her doing comes the learning and the wisdom and the real change that characterizes her work.

Speaker B:I tell people I build connectivity.

I'm a person that knows a lot of different people that are crazy or squirrely or weird as heck, but somehow when they get in a room with me, we become this United nations of possibilities and craziness and fun and humanness. So I just tell people I build connectivity as a practice for compassionate caring. I just care a lot about people and I do mothering.

I feel like mothers are the essential first responders. But as an artist, I write, I perform, I make dolls, I'm a weaver. I'm becoming a curator of museum installations.

I am considered a spiritual culture bearer and community elder.

Art of mothering workshops in: Speaker A:Part 2 Yo Mama's House Another unmistakable characteristic of a mochi's way of working is her belief that on her path, one thing leads to another. And like the unfolding story of Yo Mama's House, those things add up to something important that needs to happen.

Speaker B:My Mama's House actually started in early childhood education classroom. I was a teacher and I wrote a curriculum and asked them to let me teach it so I could see what the kinks were and how the families were.

Because we had a very diverse classroom of women who were from West Africa, East Africa, Latin American countries, Mexico, black, white, biracial families, queer families, Southeast Asian families. We just had a bunch of families with a bunch of babies. Baby. So I had three, four interpreters. And I was getting like 20 families.

I don't know, 8:00 Saturday morning. And. And they'd have 40 kids and. And we had breakfast together.

And then my kids would get go with the teachers and do things and I would have the parents. So this particular lesson was to be about creativity, the fostering of creativity and children.

Children are naturally creative, but we squelch it out of them. By the time they get to kindergarten, there's no art. They're not painting, they're not playing in clay. They've got 10 minutes worth of recess.

And it's really dismal what happens with children after early childhood education. So I put all this stuff on the table.

I put palm balls and twisty sticks and popsicle sticks and tongue depressors and glue and paint and all this stuff you can get from the dollar tree. And I started talking about child development. And also I realized I don't have anybody listening to me.

I was like, okay, what happened to my audience?

And I look up and the mothers are making flowers and they're weaving things and they're twisting things and they're painting each and they're talking to each other. Usually they sit, listen to me talk. They're telling how they hadn't done art since they were children.

Their mother used to do art, the grandmothers used to weave, and they had all these traditions that they got away from it. And they started talking about the wisdom of their mothers. And I was like, wait a minute, we got something going on here, let's talk about this.

And they started talking about how they felt isolated from each other as mothers and they had been told bad things about each other. Oh, don't go over there and live in that neighborhood. That's dangerous. Oh, don't talk to them. They're violent.

One person wanted to know about what to Muslim women do. And so it was just these rich conversations. And I basically said, would you like to do something like this?

And they would go, yeah, we'd love to do something like this. And I said, okay, let me think about it.

Speaker A:Even though she was not looking for a new job, not long after this, Amoke decided to enroll in a training program for community health workers. In that class, she met a young woman who, like her, was struggling with the class's technology and was also.

Speaker B:She brought me these beautiful paintings she did on brown paper bags. All of them are one of a kind. And she literally, for $5 they were out in the world, never to be seen again. I said, oh no, I came here for you.

I said, you need to do this and can I help you do this? I had this idea about this art making space for women and mothers, grandmothers, and found out that she had been kicked to the curb by her husband.

She had been had a botch surgery. And so she had a lot of problems that she was trying to workout. So I thought, I'll tell you what, if you can do 100 bags.

We'll put you on the map, I promise you that. And we were the first two people to do your mama's house at Juxtaposition Art. Just me and her sitting in the gallery.

She was painting and I was writing. And women would just look in and drop in and they'd stop and then they'd come in and make earrings.

And one person said, I'll teach you how to unravel a sweater and, and, and, and, and you make winter hats. So women started coming and started really teaching each other the skin skills.

So I thought, okay, we're learning traditional and non traditional skills because somebody wanted to do claymation and the Walker Arts came in and stepped in and said, how can we support you? So we had claymation at the Walker Arts. One day, Mother said they were exhausted.

So someone gave me a blueprint of a rocking chair and we went to Walker again and had a picnic and built this one rocker. Had everybody in the park, Cameron grabbing stuff and sitting around and talking.

Speaker A:That chair, dubbed the sick and tired of being sick and tired Rocking chair by its makers, became a prototype for the creation of other chairs, like the baby Mama chair, made in partnership with homeless youth at a local organization called Culture Club, the Ancestral chair with the Gaia Democratic School, and the resistance chair with the group of Northside mothers.

Speaker B:So that's how the momentum started. As I did this, I had to find spaces to do these, these workshops. So I was dragging tote bags and boxes and stuff.

One particular house, St James House here in north Minneapolis, was a place that invited the community to use the house. Beautiful house, beautiful gardens, beautiful spaces. And it dawned to me, your mama needs her own house. So I thought, what is it?

I want for the house. What I wanted for the house was what my aunt offered me. I was little and I was passed around to all kinds of families and all kinds of place.

And I knew that whatever happened, if I could just get to my Aunt Ethel's house, I would feel okay.

Speaker A:In her memoir, Missing Mama, here's how Omoke describes the sanctuary her Aunt Ethel provided to her as a young girl growing up in Los Angeles.

Speaker B:Your mama's house is rooted in my love of my aunt Ethel's butterscotch colored house on Edge Hill Drive in West Los Angeles. Love loomed large there. Love was found in her domain.

The kitchen and cast iron pots had held savory taste from all day Southern cooking and on the formica table, burdened with the sweetness of jellies, cakes and pies in her home My eyes sought the familiar stacks of cotton fabric, McCall patterns, tailor pins and scissors, Avon books with cosmetic samples, church fans and calendars from mortuaries. And an initial handkerchief my aunt had found in time to embroider.

She offered stacks, plates of foods to my starving spirit and refreshed my soul with the hum of something new from the choir. Love was wedged between the stacks of jet and sepia magazines and between their pages. Colored people's lives were important.

Love bloomed in her gardens. I fell in love with Rose. I ate citrus fruits from the trees or drank fresh lemonade and juices out of jelly jars in Aunt Alva's house.

Home and love was always the same things. And I was always safe, loved and welcomed. I wanted this experience in space for black mothers. No mothers are ever excluded.

The seed for your mama's house was planted. So that's what your mama's house was my idea of what did that. I was very blessed that an organization in California gave me a $25,000 down payment.

So that's how we got our house.

Speaker A: That:Amoke says that the reason that her Aunt Ethel's house was so important to her was that there was a real absence of mothering in her young life. The way she describes it is that her mother had her, but she did not have her mother.

So Moke created Yo Mama's house as more than a community art center. She created it as a safe and sacred space in celebration of mothering.

Speaker B:Mothering is an art. Women are having to turn on the dimes, spin around 360 degree stretches and bending over and stretching.

They can make things work all the time all over the world. And how we're put at the bottom and not resourced and our children are not educated and we're not housed. I don't understand it. I just. I don't get it.

The family unit is your smallest societal unit. If it is broken, everything else breaks or does not even get built. It just doesn't.

And most people who are healthy are really standing on the backs of their ancestors. There is the glue that's holding them together.

Are those familiar stories, those narratives, those know how to do get stuff, get done in the absence of mothers. I basically adopted a lot of other mothers. I wrote to Alice Walker. She wrote back. I wrote to her like she was a friend.

It was like she was mothering to me. Reading her stories, reading what she wrote, hearing her her mothering stories, hearing her stories about her mother.

Speaker A:Part three Angry meets well intentioned.

Given the hard work and the satisfaction of making Yo Mama's house a reality, one might imagine that its creation would represent a sort of finish line for the Omoke Kubot story. But I'm sure you've noticed that that's not exactly how omoke rolls.

So it's probably more accurate to describe the house as providing another and a long line of launch pads for what comes next. That next chapter came just before the pandemic descended by way of the Wiseman Art center at the University of Minnesota.

Speaker B:I drove the Wiseman Arts Museum nuts. We basically they just told me, never tell me I can do anything I want to do. And I was very clear with what can't I do.

Are you sure you know you're allowing me to be unleashed here? Yes, no problem. Whatever you want to do. They within a few days they were asking me to start scaling stuff back.

We had aerialists, we had jazz musicians, we had dancers, we had shadow puppets. We had 33 artists showing their art on the walls, on the tables, on the floors. I did a play. I had asked for extra rooms for breakout sessions.

After the play we always have a post play discussion. I tried to tell the wise men, the audience is not going to go anywhere after the play. So we have to have room to have them talk.

And no, that's not going to. We don't have that many people show up. It's a February, blah blah blah. Over 300 people RSVP. So we were packed. The show started at 1:00.

We staggered out of there at 5:00. The museum had never seen anything like that.

I said, this is the topic where people need to talk and they need to breathe and they need to not walk home and don't have any place to put what their feelings are. They have a lot of feelings.

Speaker A:The play that needed this time and space for reflection and grieving is called Angry Black Woman and well Intentioned White Girl. It's described as a play that goes there by expressing the daily unsaids between black and white women.

Like so many of his life Spawn Creations, its genesis is an epic story unto itself.

Speaker B:I'm known for speaking my mind and I'm known for saying what I need to say, what I need to say it. And I had been Meeting with a group of people for about six months and we were talking about the same thing and not making any progress.

And I'm teaching full time, I have children, I write when I can. And I said, I can't keep showing up. And we, we haven't got any further than we had the last time.

And I had my notes and said, okay, you were sitting here and you said this, and you said this. What are we doing? I don't have the time. And someone perceived me as angry. And I said, no, I'm not angry. I have more emotions than angry.

I'm actually frustrated. I like getting things done. I'm not excited about putting a bunch of stuff in planners and having a bunch of meetings.

I'm not a meeting person, I'm a doer. So this person considered to poke and oh, you're angry. And why are black women. I said, you know what, don't go there.

And so by the time I left, I was angry. My next stop with a friend who was hiring me to work with the after school program in North Minneapolis.

And as soon as I got out the car, she's standing in the park lot. And I just blurted out, I am so tired of being called the angry black woman.

And she just stood there a minute and she said, the well intentioned white girl. And I said, oh, you get called something too. So I said, we have to talk about this.

So we started having these conversations and I just said, you know what? I'm taking this to the stage. This is the conversation I got to have going. I think I need to drag more people in here with this.

And she and I, working together, got into a place one day, she was my boss and she stepped on my toes and she did it in front of kids. And all the air got sucked out the room really quickly. And I was like, okay. So I just said, they're yours now.

You didn't disrupted what I was doing, so they're now yours. And you figured this out now? And she said, oh, I am a black woman. One chicken white girl. And I said, yep, we're there.

But I said, because I love you and respect your work. I said, we're gonna work this out. We're gonna put this in the play. We gonna work this out.

As I wrote the play, I realized I can't write for white women. The goal was to get white women to tell me their stories.

And we had a breakout group at Intermediate Arts and we had a the other breakout group at Hope Community. We could not put the black and the white Women together was not gonna happen. And they were asked a couple of questions.

They were asked, how do you participate in Minnesota? Nice. Every time you asked a white woman, they start giggling or crying. You ask a black woman, they get mad. So it's a real dichotomy.

Just really something to see that. The other question, can black and white women be allies? Black women, right? They're talking in their throat.

They're like, the body language like it's gonna be a stretch. And white women were like, yeah, we can do this. And I'm going, okay.

So I get asked them if they did not want me to use their language or extract something from their conversation to let me know. No one did.

So that gave Jen, the other actor, the opportunity to understand where I was going with the play and the conversation I would like to have. She's amazing. Wrote the scri, did it as a public read. We had 90 people show up just to hear it read.

By the time we did two sold out, two performances sold out, they wanted a third show and I was absolutely not. I'm going to seminary at the same time. I can't do more than this. And I got rear ended three days before the play. Jen almost got hit by a car.

So it was wild. Jennifer also had children, so working with her and her family and she lives in Wisconsin, There was a lot of variables of what we're doing.

Nicole Smith, who was CCLI member with me, became our director and she started losing her eyesight. So it was quite an experience to get this play done. We were a pretty motley crew, but we got it done.

Speaker A:Here are the angry black woman, Amoke Kubot, and the well intentioned white girl, Jennifer Johnson. Getting into it on the wiseman stage.

Speaker C:This feels like somebody is, oh, join the club.

Speaker B:This is a human journey.

Speaker C:Can't you help me something, please? I'm lost.

Speaker D:You have to do your own discovery. I mean, find your own keys and unlock your own doors. Tell this to the people you know.

Your white mother, your white father, the white preacher, the white teacher. Those people, those white people who make.

Speaker B:Those racist and sexist comments.

Speaker C:You want me to die. I will be shamed, shunned, discarded.

Speaker D:Oh, you can't have it both ways. Either fix it or stay broken.

Speaker A:The play ebbs and flows with barbs, insults, and difficult truths that are both hard to hear and at times, incredibly funny.

Speaker C:I am not a criminal.

Speaker D:Yet everything I do gets pathologized or criminalized. Despite my daily attempts to do the best I can, my trauma becomes your entertainment.

Speaker C:How could you not be angry?

Speaker D:How could you not be angry? Oh, oh, you are attracted to me, my anger. Like a moth to a flame. Except you know what? We both get burned.

I can't keep carrying this unbearable weight of elective, ancestral and crushing despair. We black women, white women, we kind of coexist in this historical tango of bullshit and shame and sorrow and anger and rage.

Speaker C:Rock, paper scissors. Rock, paper, scissors. Fear, blame, crazy fear, blame, crazy rain. Violated violence.

Speaker D:Violated violence. What do I do? What the fuck do I do? Own it. Tell me how. No, please. No is a complete sentence. Then why am I here?

Maybe you don't want to do this diversity shit any more than I do. Maybe you want to stop being all fake and stony face. Maybe you just need to stop triggering and re traumatizing me.

Speaker C:I don't like this. I don't want to feel bad. I don't like it.

Speaker D:Green eggs and ham, that's why. Of Orange County. Stop being a child. Oh hell no.

Speaker B:We did that. And from there someone heard about this play in Duth, wanted us to come up there.

A woman named Missy Poer called me and said I want the play to come to Sandstone. I said I have no idea where Sandstone is. But she wrote a grant that got us up to St. Cloud, Duluth, Cambridge, Cloquet and Sandstone.

From there we've gone from, we've gone to Rochester, Grand Rapids. We've gone to about 10 places, rural places. What's interesting is most of those places do not have a large population of black people.

A lot of them did not understand the term Minnesota. Nice. Jen's character actually turned into be three characters by the time we started doing the play. She was the well intentioned white girl.

Then she became the ghost of Wonder Bread. Good old days. I was very surprised when that character start showed up. But that character really told the story of how white people became white.

Jen actually had a real interesting journey with this because she started looking at her Irish ancestry. So she started suggesting things that she was feeling in her spirit. Like ancestors were seemingly talk to her. She had a one.

One scene is where she is a mother in a ship and she tosses the dead baby into the to the waters and she sings this beautiful Gaelic song of sorrow and grief, lamentation. So it just, it keeps growing. It keeps growing.

We started inviting men to the performances and Twin Cities detoxifying masculinity came in and gave us the piece that they thought men needed to work on. So the play has gone to Kentucky State University and has been debated by the forensic Debate team people have written about it.

I would love for somebody to pick up the script and just do it in their own community. Another extraordinary thing that has happened.

The rural women who had seen the play, about 20 of them got together between the five cities and they started having book clubs to educate themselves in, in readings and, and coffee clutches and, and just started. They call themselves Compass Compassionate Community. And when they started together, they started wanting to be anti racist.

They wanted to know how could I do better? How? They wanted a world that was different than the world that they had grown in. They wanted their children to grow into the world.

That group is still going.

ort the play and hopefully in: Speaker A:Part Four Pinwheels as you've heard, Amoka's life is full and demanding.

It's important, though, to recognize that a powerful grounding for all of this is her deep connection to the spirit of the earth, the legacy of her ancestors, and her belief in the power of her intuition.

Speaker B:The Yoruba concept Ori is your divine mind. It's your first mind. It's a mind that we often don't pay attention to. We often, oh, I should have had a V8 fu.

You didn't have something that just about poisoned you. You, you really should have had that V8. It's that kind of mind. It's a mind that doesn't get censored. It's the mind that's connected to the divine.

It's connected to your destiny. It's like your own personal deity.

So I was told when I joined or became in the community of Ishi or Yoruba IFA orisha, that I had to follow my ori no matter who it was, what it was. I have a very strong sense of intuition. Oh, they were like, you have to do this. Usually people will see that. It's because it's part of my process of.

I'm determined to get to the point A, to point B, because that's where I'm being led to. And so like I said, people seek me out. I don't seek anybody out anymore.

People seek, come to me with problem solving things they need or want, creative help or whatever. Even the house was a place to.

People were just tired and they would just want to come over and just lay down and go to sleep or read or dance or go in my kitchen and cook. So it was the kind of house again, like my Aunt Ethel's house. It was like a refuge. It was a place of sanctuary. So it's a thing of mutual aid.

That's what our ancestors did. They did mutual aid. You just saw what somebody needed, and you didn't have to qualify or write an application or do some planning or.

It wasn't transactional. This person needs to eat, get up and feed them. We took care of each other.

Speaker A:Amoke also describes times when the opportunities, the need to respond just makes its presence felt. And her spirit, her intuition, just takes over and leads her.

Speaker B:I go down to the river and I pray.

One of the easiest art projects I ever did was I was trying to figure out how to transform the energy in north Minneapolis when the police were killing people over here on a regular basis. In this time, that means that Jamar Clark was killed.

And I just thought, I'm ready to just go out in the street and just really do some voodoo, do something. But I can't take this anymore. And I can't sit around and just wring my hands and be nervous about, I gotta do something.

And my elders were like, no, you just can't go out and just do anything. And I thought, but something has to change. So, oh, yeah, as an orisha, that is considered the energy of change.

So I went to the dollar store and got these pinwheels.

And on the pinwheels, I wrote on the petals all the things that I wanted to blow out of Minneapolis, or all the things I wanted to be blown into Minneapolis. And I took them down to the river and I stuck them in the. In the riverbank and I prayed over them.

And I brought the pinwheels home, thought about it, and said, okay, I think I need to give them to people. I made a hundred of them. I did. Just did a hundred of them.

And I happened to be driving, and they were in the backseat of my car, and I saw a yard sale. So I went up to the people in the yard sale and said, look, this is what I've done. This is what I'd like to do.

And I thought they were going to say I was corny. I thought a crazy old lady.

And they started taking these pinwheels by the handfuls, and they were like, I'm putting them in my yard, going to put them in my. I'm going to take them to my church. And they started.

These pinwheels started popping up I took a handful of them down to J, where Jamar Clark was killed. They ended up ending up in places like the mayor's office. They ended up in schools. The seminary started making them with me.

People started coming to my house to make them. So these pinwheels went out with the prayers of the people to hold things together and hold things down. So that's how my work goes.

It's like a response to something. And that's what my passion is. That's connect. And we're stronger together.

Speaker D:We're.

Speaker B:We're better together than we are alone in isolation and fear. I've learned for me, I don't need to know all of the creator spirits mysteries. I really don't. And so that takes a lot of weight off for me.

You don't have to know everything because I think this culture is into. You have to know everything. There's some kind of stigma around that you could be possibly stupid or dull. So I don't have that.

There's a lot of ways of knowing, and I have some of those. I. I just do what I hear to do. I am more right now just focused on art making because that.

That is giving me life in this time where it is just so insane and I've stopped trying to make sense out of what's insane. You can't. I. But other than that, no, I. I don't have that angst anymore. That's gone. I don't night. And. And some part of me is still very optimistic.

I really believe in human beings, that we can be better.

Speaker A:Given all that she's been through and all that she's done, the simple but powerful belief that we humans can be better has, I think, functioned as a kind of a North Star for a Moke Kubot. And hopefully after hearing her story, it can resonate in some way for you.

So thanks again for lending us your ear and also, if you're so inspired passing this story and its companions on Change the story, Change the world onto your friends.

And hey, if you have some comments or questions or ideas about how we can expand the Change the Story community or people you think we should be talking to, please drop us a line@csacrtandcommunity.com that's CSAC. And please know that we read and try our best to respond to everything.

Change the Story, Change the World is a production of the center for the Study of Art and Community. Our theme and soundscape spring forth from the head, heart and hands of the maestro Judy Munson. Our text editing is by Andre Nebe.

Our effects come from freesound.org and our inspiration rises up from the ever present spirit of OOP 235. So until next time, stay well, do good and spread the good word. And rest assured, this episode has been 100% human.