Transcripts

First things first: self-awareness isn’t like a single moment of enlightenment, or an off/on switch. It’s a matter of degree (or type, as we saw above) and we can be self-aware at some times, less so at others.

We can define self-awareness as a conscious perception of thoughts, feelings, events and behaviors, both internal and external, that is accurately grounded in reality.

The opposite of that is anytime we’re unconscious (i.e. acting out of habit, impulse or autopilot) or not thinking about how we’re thinking. When driven by unconscious impulses and biases, we cannot recognize patterns in our world, and hence we can’t take proactive steps to change anything. So many other positive characteristics and traits are impossible without the bedrock of self-awareness, and yet there is little out there that teaches us how to build it within ourselves. And why would we, when most of us think we are self-aware already, right?

With self-awareness comes:

• Self esteem

• Sound decision making

• Creativity

• Self control and emotional regulation

• The ability to develop and evolve

• Humility and awareness of weaknesses

• Pride

• Empathy

• Communication and cooperation

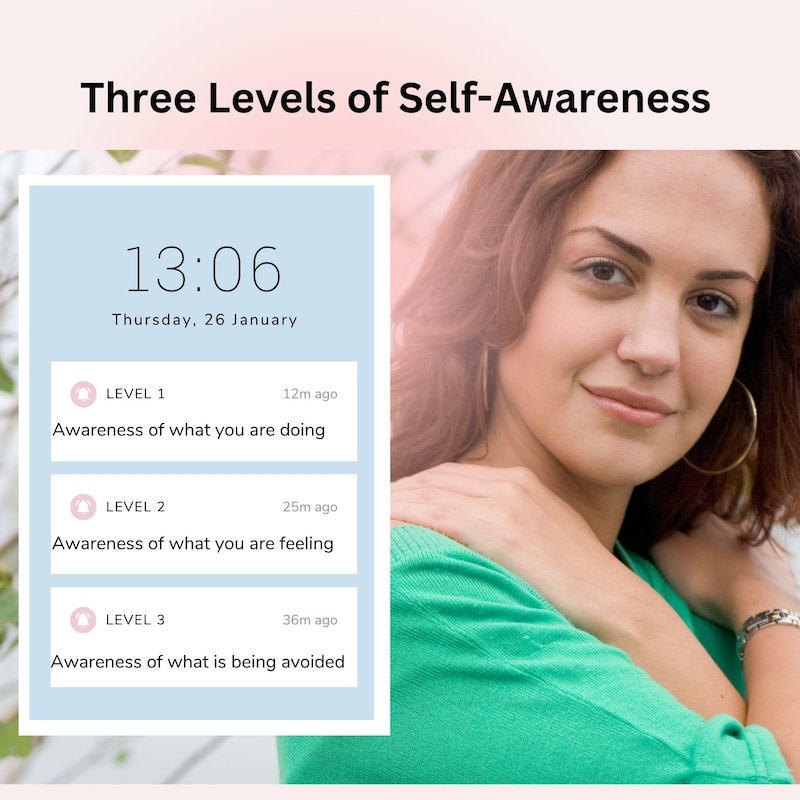

However, reading the above list, you can probably see that it’s all shades of grey. To simplify, we can imagine there are 3 levels of self awareness we can operate from:

Level 1: What are you doing?

Pain, confusion, suffering, stress, irritation, misunderstanding, struggle etc. life is This is like at low levels of self-awareness. If you’re unhappy with work, relationships, money or life, you probably have some self-awareness blindspots. In this mind space, we are unhappy yet unaware of the reasons why, unaware of our role in the problem, and oblivious about what we can do to fix it.

Signs you’re in this level include any behavior that transports you out of the present moment. This could include numbing yourself out with distractions and addictions such as gaming, mindless social media use, substance abuse, or bingeing – whether on food or media. We avoid obligations and feel so anxious, angry or apathetic that we procrastinate. Worse still, we aren’t even aware that we’re doing all this.

For example, you have an awkward discussion with a family member and find yourself overeating that evening and feeling too lazy to do any chores. Then you go to bed late after a four-hour gaming binge and wake up the next morning with a sour mood and a sore head. But you don’t understand why any of this is happening. You are unaware of how you feel after the conversation, you are unaware that bingeing and gaming were your coping mechanisms, and you’re unaware that the reason you feel so bad the next morning is because of these choices.

So you have a vague, dull sense of “my life sucks” and you march onwards, oblivious, and unable to help yourself. How could you, when you are unaware of the nature and existence of the problem? Distraction is destructive. But infinitely more destructive is any compulsive behavior that we are not aware of. Without awareness, we are slaves at the mercy of… well, everything. We forfeit our free will.

Don’t try to vanquish distraction – the harder and more pressing task is to just learn you are distracted! How often have you fallen down an internet rabbit hole, when you don’t even remember what brought you to your phone or laptop in the first place?

This is the frustrating paradox of self-awareness: we think we are so much better at it than we are. To prove this point, try a simple exercise: simply become aware of how much time you’re spending on distractions. Changing behavior comes later – first, we just want to learn of the extent of addictive, compulsive behavior. Many people deliberately waste time or indulge in a little distraction, but they do it with full conscious awareness. Different story. Likewise, if you’re completely mindless during a meditation session, it’s as useless as if you were gaming or stuffing your face or losing hours on a Netflix binge. The behvaior is only a symptom; the real issue is awareness.

If you are at level 1 (most of us are at some point) then try to objectively track and monitor your distraction behaviors for a fixed period, such as a week. You can use an app to track your social media or gaming use, or you could commit to jotting down precisely what you eat and when every day. At this point, you are not judging these observations. You are just becoming curious about what is happening, and to what extent.

Level 2: What are you feeling?

When you become aware of and gradually start to remove distractions, you will be confronted with all the emotions those distractions covered up. What you’ve been avoiding will come rushing out in full force. If you’re the kind to get freaked out by silence or having nothing to do, this will likely be why! When we have unprocessed, unacknowledged emotions (i.e. emotions we’re not fully aware of) it hurts. We would do anything to patch over them with more lovely, safe distractions.

This second level of self-awareness comes from understanding not just what we are doing (scoffing tubs of ice cream) but why we are doing it, and how it feels (you’re stressed and angry, and need the comfort of something sweet). When you are in touch with what you actually, genuinely feel, and are no longer distracted and numbed out by the carousel of everyday distractions, you start to have original thoughts, and become aware of feelings you never even knew you had.

For example, a woman spends 20 years of her life married to a man, but one day thinks, “oh my God, how did I end up here? I have nothing in common with this person.” Throughout her marriage there was some comfortable distraction: raising the kids, keeping up with work, moving house, dealing with family crises… but when the couple retire together, there is for the first time in years a quiet moment where the ordinary distractions are absent. The feelings that have always been there are more clearly revealed. The doing has concealed the feeling. Had she asked “what am I doing?” and answered honestly, she might have answered, “avoiding facing the truth” and simultaneously discovered what she was feeling. This is the way that level 1 awareness can inspire level 2 awareness.

Maintaining awareness can be difficult because facing certain emotions is uncomfortable. It hurts! We don’t want to know how afraid we are, or angry, or weak. Many people spend their entire lives having literally no idea how they feel. Instead, they mimic others or repeat stories about what they think they feel, and anytime they get even slightly close to being aware of deep, genuine feelings, they abruptly switch off and engage in distraction and addiction instead. After all, being aware of difficult feelings usually means we have to take some action – leave a partner, quit a job, do better, make an effort. And that can be scary.

At this level, there is one powerful but tricky lesson to master, and that is that emotions are just… emotions. They are always there, flowing like the sea, but they don’t necessarily mean anything, and they are not the be-all and end-all. When you are conscious and accepting of them, you discover something important: they flow on. You don’t have to chase “good” emotions or run screaming from “bad” ones. Feeling a lot isn’t necessarily profound. In fact, emotions in themselves can be distractions… from other emotions!

Again we arrive at what’s important: not the emotions themselves, but the awareness behind them. Don’t become that person hooked on an “enlightenment” loop. You need not get lost in endless self-reflection (like the “introspector” described above). Remember, navel-gazing is not the same as self-awareness. The feeling of profundity and awareness is not the same as actual awareness (don’t analyze that too closely!). You could get addicted to the process of endlessly digging through layer upon layer since you will always find something that feels pithy.

But is it? Does it illuminate, clarify and show you what’s what? Usually no.

Digging down to ever-deeper layers is a trap because it only feels important. Practically speaking, it creates anxiety rather than self-awareness and genuine insight. We’ll look at anxiety more in later chapters, but although emotions are valid, they are not a substitution for self-awareness. Emotions can help or hinder. They can be appropriate or inappropriate, helpful or unhelpful. But they all pass. And we can strengthen our ability to “sit with” our emotions, without clinging or judgment, and fully know what they are while still not allowing them to push us around.

Level 3: What are you not aware of?

You can become aware of what you’re doing, i.e. your behavior. You can become aware of the associated thoughts, emotions and beliefs around that. But the final level of self-awareness is bringing into your conscious mind all those things that you are not aware of. If you are diligently focusing on your actions, thoughts and feelings, you’ll soon notice something: how much nonsense there is. Really.

You may have a bunch of ill-conceived and rather stupid ideas, kneejerk reactions, habitual behaviors that don’t make sense, automatic responses you just inherited from someone else, big heaping doses of arrogance and ego, fear, stubborn opposition and resistance, lazy thinking, and ideas you cling to desperately despite them being irrational and outdated. Oh, and on top of all of this, you probably still hold tightly onto the idea that you are an impressive independent thinker, ultra-smart, kind, funny, and generally one of the good guys. Right?

Here lies one of the first big obstacles to genuine self-awareness: we’re stubborn idiots who believe we already are self-aware! Yet the research consistently shows that our memories are unreliable, that we overestimate our abilities, that our focus is often distorted and self-serving, that we lie a little to make ourselves feel better, and that we’re not all that good at assessing risk, making statistical judgments or genuinely taking on board constructive criticism.

Phew! Here’s the thing, though: none of this is a problem, so long as we are aware of it. This is an issue only if we are plowing ahead with it, unaware. We all have weaknesses. The true test is not to be faultless, but to bravely and honestly accept the faults you have, and take reasonable action to work around them.

Many of us unconsciously believe that a heightened state of self-awareness is simply everything we hold in our minds, only somehow amplified. In fact, the process of developing increased self-awareness is often felt to be a diminishing project, because we lose precious illusions, patterns, fantasies, unrealistic expectations and all those problems we were creating for ourselves. It’s taking ourselves less seriously, getting real, and admitting that we know a loss less than we thought we did.

Imagine a guy who prides himself on being a deep thinking academic type. Immediately after finishing his first degree, he dives into another, despite not being able to afford it, and despite it being unnecessary for his intended career. He spends a lot of time fretting over getting it all done, and makes a martyr of himself, secretly relishing how impressed everyone sounds when they hear he is tackling yet another degree. He fills his days with a busy schedule of what he believes is enriching self-development. He even feels a little superior to those who haven’t acquired his academic achievements. All the while, he is an intelligent individual dutifully going to therapy each week, where he uses big words to talk about everything from his minor family dramas to his girlfriend.

Looks pretty good. But what is he not aware of?

If he were honest and had genuine self-awareness, he would see that his insistence on being a lifelong student is a way to cope with the fear of actually going out into the world to get a “real job.” Rather than tackle his blind spots and weaknesses head-on, he plays at tackling others that feel easier to manage. Nobody can say he isn’t working on himself if he’s feverishly pursuing his education, right? He has concealed the real reason for his actions even from himself. His careful avoidance of having to face his fears of inadequacy and failure means he never mentions it to his therapist, and she never asks. So long as there is a mountain of coursework for him to get through, he spares himself the awareness of what has been forcefully shoved aside: the immobilizing terror he has at the prospect of having to work.

One important thing to realize is that we can only be better with empathy and understanding other people’s emotions and thoughts, once we are operating at all three of these levels ourselves. If you are a person religiously avoiding your emotions in your own life, all you could do when confronted with someone else’s strong emotion is to avoid it in much the same way. If you’re the person whose coping strategy is to numb out pain with distractions, then what insight could you generate into the causes of someone else’s life troubles? This is perhaps what people mean when they say that your relationship with others reflects the relationship with yourself. The guy in our example above may never encounter his unconscious drives, but he will see hints of it: in his disproportionate judgment of “losers” and in his inability to tolerate fear and self-doubt when he finds it in others.

To support our goal of cultivating greater total self-awareness, internal and external, we have many tools at our disposal. We can commit to holding weaker opinions, taking ourselves less seriously, and being honest about our blind spots and ingrained patterns. We can learn to anchor in reality and actively seek the feedback and perspectives of others, and have the courage the face our weaknesses and actively change them.

Kegan’s theory of adult development

Let’s consider a model that can help us pull together some of these ideas around awareness, which as we’ve seen, is not so much a fixed trait but a skill that can be refined and practiced over time. The fact is, self-awareness is a capacity that grows with us. Our perception of self and others, and how well we know the rules for engaging with them, start evolving from the moment we’re born. While most people understand that children develop according to milestones, they might not be aware that adults do, too. In fact, according to psychologist Robert Kegan, adults mature along a course of 5 developmental stages.

And what makes a mature adult? It’s the ability to gain both awareness of the inner self and grow in social maturity, responsibility, independent thought, self-control and wisdom. Kegan’s research estimated that a full 65% of people do not make it past stage 3 of 5, meaning they do not become “high functioning” with social behavior, relationships and work.

The key is, surprise surprise, awareness. So let’s begin with the obvious: we need to know what the stages are, and where we fall. This gives us something to aim for, and helps us think clearly about the capacities we’re still developing. But before we race ahead with the stages (admit it – you’re dying to know how you score, right?) let’s clarify two important related concepts that underpin the overall theory.

The first is transformation. Consider a caterpillar. To develop, it’s not enough to simply be a better and better caterpillar. Instead, a complete shift is required, i.e. it needs to become a whole new being: a butterfly. With humans, it’s the same. The developmental path is not to simply learn new things and refine existing skills – it’s to completely change the way you perceive and engage with the world. The former is about changing what you put in the container, the latter is about completely changing the container itself. We are not merely growing, but transforming.

The second is the subject-object shift. Kegan believed that as we develop and mature as adults, we necessarily undergo a shift from knowing the world as a subject (that is, something that controls us) to knowing it as an object (something that we can control). In the first mode, we are bound up and tangled in self-concepts and unable to reflect on them – we feel like are them. In the second, we can detach from these self-concepts and consider them as something separate from ourselves. As we do, we realize our agency and ability to change, control or reinterpret these concepts. We become more “objective,” more proactive, and we develop this all-important capacity for self-awareness.

Subject – “I am” i.e. total identification, the concept controls you (example, “I am a father, it’s just who I am”)

Object – “I have” i.e. can perceive from a distance, you control the concept (example, “the fatherhood role is something I have, it’s something I can choose to do. I can step back from the idea and make conscious choices about what being a father means.”)

A further example will clarify. When we’re younger, we may automatically identify with our parent’s political beliefs, and say something like, “I’m a liberal” without thinking too deeply about it. We are in subject mode, and take this perspective as a given, and something that determines us, rather than something that we determine. Later, as we grow up, we see ourselves as independent agents, i.e. people who have beliefs – and if you take on a belief, it also means you can drop it, too.

You may have an epiphany in early adulthood where you realize that you are actually in control of what you believe. Stepping back, you can reflect on the issues independently, and make a choice about your perspectives and beliefs, and consequently how you will act. This is a drastic transformation. Before, you might have automatically behaved in the way that you thought “liberals” behaved, i.e. you lacked self-awareness. But now, the concept of “liberal” is something you are free to choose, or not. Being aware, you may well choose the same thing again, but it is now from a completely different and more mature perspective. From the objective perspective, your feelings and thoughts are not who you are, they are something you have. If you are aware of this fact, then you can choose. As our awareness and consciousness evolve, we advance in maturity.

Most of us are somewhere between stages. Each stage is characterized by what is achieved as an object, i.e. what area of life we can transform and experience a subject-object shift in. Few go beyond stage 3.

Stage 1 and 2: The Early Stages

From early childhood to adolescence (or, to be frank, adulthood for some)

We’ll consider the early two stages only briefly, as they largely correspond to childhood development. The earliest stage is called incorporative, and there is little sense of self to speak of, i.e. no distinction between self and other. Infants and babies are more or less enmeshed in their sensory experience, and their task is the transformative understanding there are things out in the world that are not self. So, in Kegan’s terms, the child learns to think, “my reflexes and sensory awareness are not me, they are something that I have.”

From around 6 years onwards to adolescence is stage 2, called the impulsive stage (exact terminology varies). Here, the self is learning about impulses but is still very identified with them. Whilst babies have no understanding of anything objective at all, and inhabit only their own perspective, in the second stage there is a growing awareness of others as independent beings. However, these beings, for example, parents, are still perceived concerning the self’s own impulses, and in terms of how they satisfy those impulses or not.

If you are at stage 1 or 2, the emphasis will be exclusively on your own needs, perspectives impulses, agendas and desires. In so far as you can appreciate other people, your engagement with them is transactional, i.e. to meet your desires and needs.

Subject: the self IS one’s needs, interests & desires

Object: the self HAS impulses, perceptions & emotions

Such a person may act morally and consider the needs of others, but it’s always ultimately to serve their own needs, for example, kindness is given expecting it will accrue benefits for the self later on.

People in these early levels are low in internal and external self-awareness, and they align with ideologies, philosophies, perspectives and rules, not from genuine belief, but from a feeling there is some reward or punishment associated with doing so. For example, if you asked someone in this stage why stealing was wrong, their reply might talk about the legal consequences or punishments from others (subject mode) rather than the innate ethics or the appeal to personal values (object mode).

Stage 3: The socialized mind

From adolescence onwards

Subject: IS interpersonal relationships

Object: HAS needs, interests & desires

According to Kegan, most of us stop developing at around this stage. We can consider that it’s here that our external self-awareness develops – i.e. where the outside world shapes our perception of both self and reality.

The focus at this stage is on ideas, beliefs, conventions and norms as they are presented by the social systems around us. So, we look externally to our families, our societies, our histories and our cultures to determine who we are and what we believe. We experience ourselves as others experience us, substituting their view for our internal experience. For example, if those around us tell us “You’re worthless” then we don’t say, “They think I’m worthless” but rather “I am worthless.”

We may spend a lot of time managing and taking responsibility for other people’s experiences, and require external validation to feel any sense of value in ourselves. This is the phenomenon of not knowing how to rate or appraise something until we’re sure how others will rate it. In a deep sense, we are unsure of whether we are good or bad until someone or something tells us we are.

We may appear to have high external self-awareness, but we lack an independent sense of self (internal self-awareness) and struggle to understand what we value, what we want, or who we are, outside of other people’s perspectives. To reach this stage, we now no longer view relationships as transactional, and we know that other people possess their own perspectives. However, the interpersonal relationship is the focus and we can care so much about what others think that we internalize their perspectives.

If you ask a person in this stage why stealing is wrong, they may answer in terms of values and belief systems, or the effects on important social relationships. However, these values and beliefs depend on external rules and ideologies. The socialized mind says something like “I am my relationships. I follow the rules.” Note how this is the subject speaking.

Stage 4: The self-authoring mind

Subject: IS self-authorship, identity and ideology

Object: HAS relationships

Kegan found that whereas around 65% of adults inhabit the previous stage, just 35% fall into this level. Here, a person may still not detach from their identities and personal ideologies, even though they have made the realization they are not their relationships, but rather they have relationships. This is the level where we are no longer defined by others, by our society, by our relationships, or by our engagement with the environment. Instead, we self-determine. The big understanding is that we are autonomous humans with feelings and thoughts independent of others, and the environment.

At this stage, we may be heavily focused on the person we are, as exemplified by our values, desires and limitations. We know how to stand up for what we believe in, and our ability to think independently gives us our unique voice. Because we take responsibility for our own state of mind, we have a more nuanced, contextual understanding of the world and ourselves in it. We’ve had the experience of ourselves as purpose-driven and value-oriented, and we understand that we can change these things about ourselves.

Ask such a person to explain why stealing is wrong and they will give you a highly original, carefully considered response that centers them as authoritative, moral beings who can choose their values and their aligning actions. They may something like, “others can steal if they want, but humans have free will, and I choose to be a person of integrity. I’m a good person, and I know, in my heart, what is right. Character comes from our choices, and my inner compass tells me the right choice.”

Stage 5: The interconnected mind

Subject: IS

Object: HAS self-authorship, identity and ideology

Kegan claimed that just 1% of people ever reached this stage. Here, the person’s sense of self is not attached to any identities or roles. Instead, there is only endless exploration of potential identities, roles, perspectives and engagements with others. The self is dynamic and ever-flowing, and we can spontaneously and repeatedly find balance in every emerging moment. We consider both our inner experience and the feedback from others. We can appreciate and “hold” complexity without needing to collapse everything into a concrete, fixed set of concepts that we are then held prisoner to.

We are expansive and unlimited. As our circumstances change, we change too. We are able to do something that is only associated with this stage: contain paradox. We are not only comfortable genuinely considering perspectives outside of our own, but we can also inhabit them and apparently opposed viewpoints simultaneously. We can “contain multitudes.”

Ask a person in this level about the morality of stealing, and they will be able to question the very frame of reference that makes such a query possible. They will easily entertain the full arena of possible perspectives on the question, perhaps even generating novel and original models or theories about the concept of morality itself (“who is this Kegan guy anyway, and wouldn’t I like to make my own model instead?”). They will become interested not just in the different ideas, but in what connects them, what lies underneath and beyond them, and the meta-perspective that allows contradictions to dissolve.

They won’t cling too hard to any of these ideas, however, and will not wear any pet theory as a cloak of identity – in fact, you can expect them to handle their contemplations with humor and irreverence. They can seamlessly and without ego set down one set of assumptions and genuinely consider another set, zooming in and out and ultimately abandoning assumptions completely.

They are comfortable with not making definitive pronouncements. They understand that intellectual faculties can be utilitarian, i.e. something that you have and use, rather than something that you are. One way of knowing and thinking will work at one time and in one context, but not in another. Their skill lies not in the content of their thoughts or the quality of their connection to others, but in the fluency with which they can adopt both.

So, which stage are you currently in?

Kegan found something similar to Eurich and colleagues in that most people overestimate their maturity and awareness. You may have resonated with some descriptions above, but remember that we can straddle stages, occupy certain stages intermittently, or confuse being at a certain level with wanting to be there.

To be on the safe side, assume that you are one level below where you think you are. According to Kegan’s theory:

• We advance to higher levels when we make transformations to our style of knowledge and engagement (both of which require awareness)

• We transform when what was once viewed as subject is viewed as object, i.e. we make a subject-object shift

• What is acquired and mastered in one level is the challenge for the preceding level. Thus, to advance, we need to make the appropriate transformation and shift what we currently hold as a subject into an object.

This sounds more complicated than it is. No matter which level we’re at, our developmental goal is always to change our subjective experience of the world into objective, i.e. place more and more of our self-concept under our own control. Let’s look at the example of religious views.

Stage 1: You don’t even have a self, you are merely a collection of sensory perceptions, and the overarching need to be loved and cared for. You ARE those needs.

Stage 2: You soon realize that you are a separate being from your parents, and that you as a being have needs, rather than being identified with those needs. As a young teenager, you can see that your parents are independent of you, but you consider them only in terms of how well they provide you with the love you need.

Stage 3: Once you can see you are a separate being that has needs, your focus shifts to your all-important relationship with your parents. You identify as their child. You are identified with the attunement, relationship and connection you experience with them. They are Christians; this means you are too. As you grow into young adulthood, your culture, educational environment and friendship circles are Christian, and, since you value them and your relationship with them, you concur and are a Christian too.

Stage 4: You realize these relationships, though important, are not the essence of who you are. With identity and ideology, you feel that you are a self-determining being who isn’t defined by relationships but merely has them. You instead define yourself on your terms – you may wonder deeply about the Christian faith and grow attached to other self-concepts. Maybe you run away to the mountains to become a Buddhist, and you focus intently for years on your ability to author your own experience.

Stage 5: You run out of money and come back home. You haven’t found enlightenment, but have a deeper realization: that your Buddhist identity was also just something you had, and not something you were. You are happy just to be, and keep your identity fluid and responsive. You return to Christianity and see it with completely new eyes. One day, while you’re out walking, you have an epiphany and realize that, from a certain perspective, you have been a Christian all along… as well as Buddhist… and Jewish too… plus a complete atheist…

Kegan saw maturity as a function of expanding objectivity, and for him, being objective was a question of distance instead of identification. That distance is the same thing as self-awareness. In the chapters that follow, we will essentially look at practical ways to develop objectivity in ourselves and gain self-awareness as we do so.

Summary:

• There are two types of self-awareness: internal (how aware we are of our thoughts, feelings and identities) and external (how aware we are of how we are perceived by others). Internal awareness doesn’t always imply external awareness. We can be seekers (low on both types), introspectors (high only on internal SA), people-pleasers (high only on external SA) or fully aware (high on both).

• Self-awareness develops as a capacity throughout life, and progresses through stages. Level 1 concerns the awareness of what you are doing and the causes of behavior. Level 2 is about awareness of what you are feeling, which is often concealed by what you are doing. Level 3 is awareness not only of thoughts, feelings and actions, but of what is being pushed out of awareness or avoided. This is the stage of deeper insight into the self.

• Kegan’s theory of adult development showed that self-awareness matures with age, with people gradually acquiring more objectivity. We can progress through stages, where we transform (that is, change the way we perceive, rather than the content of what we perceive) and make subject-object shifts.

• We mature when we transform from subjective experience to objective. This can be simplified as the ability to see you “have” a quality that you can step back from and observe, rather than you “are” a quality that you are completely identified with.

• We can see increasing self-awareness as a project of gaining more objectivity in place of subjective identification.