Shownotes

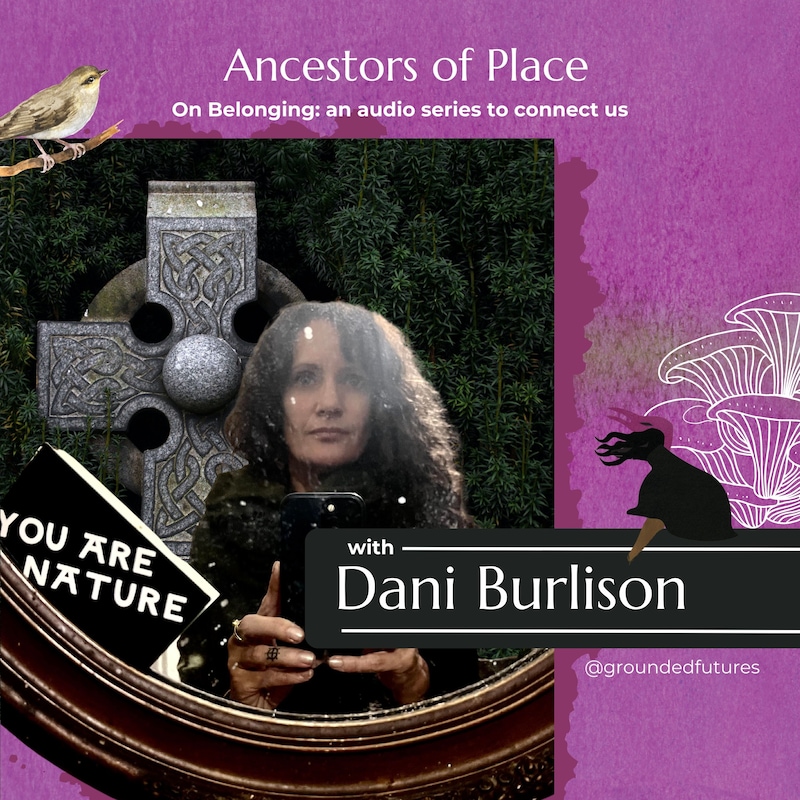

Ancestors of Place is Dani’s beautiful and ghostly pilgrimage across lands and water, weaving together an intricate tapestry of what it means to explore ancestry and belonging amidst fractured histories, colonialisms, patriarchy, and capitalism — while searching for a deeper sense of home.

Transcripts

SPEAKERS

Dani, Jamie-Leigh, carla

[there is instrumental music and soundscapes woven throughout the show]

carla:Welcome to On Belonging, an audio series to connect us. On Belonging explores why so many of us are feeling called to find a deeper sense of belonging, whether with our ancestors or to land where we live. And beyond.

Jamie-Leigh:

These powerful stories and conversations are an invitation into the lives and landscapes of the guest' worlds, offering pathways towards remembering and finding more belonging.

carla:

The following narration features Dani Burlison.

Dani:

Ancestors of Place, written and read by Dani Burlison.

Dani:

In Scotland, I board a train in Edinburgh and head along the coast of the North Sea before transferring to a bus to St Andrews. I walk the cobbled streets, eat a hard boiled egg and a few gluten free oat biscuits. Visit the old Abbey ruins and stop at a gift shop where I buy two tiny bottles of local whiskey, offerings from my ancestors.

Dani:

I climb aboard another bus, this time heading to my final destination of the day. My stop is called Road End. A rural spot along the A- 917 highway near Boarhills, a windswept coastal Hamlet with just a few small stone cottages sprinkled across the gently rolling landscape.

Dani:

I disembark and begin walking toward another of my ancestral villages.

Dani:

In much of the UK walkers can access historic places through something called Right to Roam. This usually means crossing mores or mountains or other open space to get there. Sometimes people meander along the edges of farmland and sheep pastures, as long as it is done with respect. Locals in various parts of the UK assure me it's okay to do this. But I still feel awkward. Thinking back to my rural California childhood where farmers all had guns and would point to NO TRESPASSING signs as they hollered for you to get off their land.

Dani:

I'm nervous about trespassing and being disrespectful. But I'm also determined to find the place now unoccupied, where the Pitmilly family lived for generations. Most of their names are unknown, but they were believed to have been here since the Neolithic period. And I do know the name of Eva, an ancestor who lived here in the 12th century. She was the matriarch of Clan Hay, and over hundreds of years her descendants married into several other Scottish clans, eventually resulting in my birth in California in the 1970s.

Dani:

As I walk the highway, which is mostly empty of cars, I find Kenly Water, a large creek that Pitmilly Burn a small stream runs into. I pass a grain mill and the Bronze Age tumulus that stands on what was once Eva's estate catches my eye.

Dani:

I make my way through an opening in an old stone fence and walk along the stream.

Dani:

my nervous system sparks up with a mixture of overwhelming ease. I think about how much the land has likely changed over the nearly 900 years since Eva lived here. Birch and oak growing and falling and the trails the ancient people here once walked and lived and laughed and shared stories on, now paved over.

Dani:

I sit near the stream and listen to the birds sing, they might be rock pippits or chiffchaffs but honestly, I'm clueless about which birds sing which song, so I just sit and listen. soaking up the feelings of excitement for finally reaching this land I have read and obsessed about for a decade.

Dani:

I had come to Scotland the second time for writing residency and decided to stretch my trip into two months of visiting the dead as sort of Eat Pray Love for Goths I suppose. I'm also here to contemplate my sense of belonging both here in the land of my Scottish lineage and back home and the community I have cultivated in California.

Dani:

Before and after this visit to the Pitmilly land. I repeat these tiny pilgrimages over and over from Scotland to Wales and all over England, Kilmaurs in west Scotland, Yester Castle near Gifford, Paisley Abbey in Glasgow, Melrose Abbey, Tintern, Wales, and a long list of other places where my ancestors had lived and died, where they were buried where they likely worshiped.

Dani:

I tick off boxes on my inner-sentimental childhood bucket list and go to Loch Ness and Glastonbury and Sherwood Forest, the home of Robin Hood; I take trains and buses and walk miles to visit Avebury, the West Kennet Long Barrow, Lindisfarne, Isle of Skye, Stonehenge, and the sacred springs of Bath. I leave offerings at sites of witch burnings and where executions of the poor took place; I visit the oldest pubs I can find, pay respect at the shrines left to people like William Wallace and Boudicca, and venture into the High Gate Cemetery in London to offer a nod to the graves of Karl Marx and Christinna Rosetti.

Dani:

I walk through London to a flat where one of my favorite musicians, Joe Strummer of The Clash, once lived. I visit the Crossbones graveyard, an old popper and sex workers cemetery in central London, and leave an offering to the 1000s of unnamed dead below the surface.

Dani:

I feel comfortable here, the land and air feel familiar, but part of my sense of ease here is surely connected to the fact that I'm a white English speaking person in a predominantly white English speaking country. Aside from my strong Northern California accent, I blend in. I look like the people I pass by train stations or chat with in pubs. I feel confident transferring buses and walking alone day or night. I disappear into a sea of people that share my wild Celtic hair and green eyes, especially in Scotland when the wind blows in across the Irish Sea.

Dani:

I feel assured, knowing the names of hundreds of ancestors, and knowing that 1000s of ancestors are lurking around me, their presence felt so strongly on this land. And I'm an American citizen. And with that comes a huge amount of entirely unearned privilege of travelling freely without question to most places in the world.

Dani:

It also comes with the privilege of accessing my genealogy, having records dating back over 1000 years and two of my lineages. I have the immense privilege of these things, which many others do not. This is the reality of colonization and the world we live in. I never take it for granted how lucky I am to have this information.

Dani:

As a single cash strapped mom, my trips abroad have been very few and very far between. But I'm an empty nester now and for the first time in my life, I unexpectedly have the cash to make this trip happen. So I cram in as much as I can. Even the museums. I have a lot of feelings about museums and most of the not great feelings are reserved for places like the British Museum, notorious for taking what is not theirs and keeping relics -- conduits between modern humans and their ancestors and ancestral lands enclosed in glass cases. Security guards loomed nearby to ensure the physical connections between object and human are not made.

Dani:

But I go there anyway to the British Museum during the same trip for an exhibit called The World of Stonehenge. The artifacts for this exhibit are housed in one of their timed paid access only side exhibit rooms on the first floor, and includes not only items unearthed near Stonehenge but carved Pictish stones, treasures from shamanic burial sites in the Scottish Highlands. The infamous 11,000 year old red deer masks unearthed at the Starcar Mesolithic archaeological site in North Yorkshire.

Dani:

Ancient oak columns from Seahenge, bronze cauldrons, amber gold and jet jewelry, the bronze Nebra sky disk from Germany, the oldest known map of the night sky, and numerous treasures unearthed near other sacred sites throughout the UK, Ireland, and across northern Europe.

Dani:

The exhibition area is dimly lit with the only lighting focused on the artifacts themselves. Everyone speaks in hushed whispers moving in slow motion through the room. I feel rushes of something like deja vu and dizziness overtake me again and again as I peer into the cases of jewelry, tools, ceremonial items. I try to comprehend time and space and the fact that some of my ancestors either saw some of these items, especially the carved stones, when they were a part of ceremonial life. At the very least I'm certain some of my ancestors likely knew about the people and objects from the various sites featured in the exhibit. Maybe they listened to tales about these places and objects around fires, passed the stories down to their children in a constantly evolving unbroken chain of tales-- where their people were from, how they tend to the land, how they mark the cycles of worship and hard work and new and passing life.

Dani:

My feet feel so firmly planted on the ground this rainy March afternoon, but my head could float away, and it spins and spins. Then a deep grief wells up, pain and conflicting emotions about how I have access to these artifacts, part of people's lives and culture, including my own, that have been dug up from Sacred Ground. From the graves of honored people who had once been central to their communities. They're now just bones inspected by scientists with their belongings on display.

Dani:

I can't remember how long I've been in this room among these relics of the past, but I sit to catch my breath, stand in awe, choke back tears then sit again.

Dani:

Time feels twisty and off. Like I've been in here staring, having a full on existential crisis for 1000 years and just five minutes at the same time.

Dani:

During my time in the UK, I've been immersed in a training to become an ancestral lineage healing practitioner, through ancestral medicine, (as taught by Dr. Daniel Foor). I came to this work several years earlier as I searched for meaning and belonging in my own life, and have come to discover how powerful it can be to help others connect with their own people. I've seen it reduce things like cultural appropriation and insecurity. And I've seen how it's helped people find ways to make their communities stronger.

Dani:

It is not easy work, especially for folks who have a hard time looking honestly at the damage their ancestors have wreaked on the world. But it has been very worth it to me. I've worked to heal my own lineages. 75% of them are from the UK and Ireland. And in the process, I noticed something so heavy with my ancestors, and in one line in particular, a feeling of a bottomless gap, a brutal severing, in the line between when the last person born there left their land of origin and finally arrived in the so-called new world of America. It felt as though they left a part of their physical self behind when they stepped onto that ship that carried them away. They left their language, their customs, their relationship to the land, and they left their ancestors behind in that very soil.

Dani:

As I walk out of the museum and make my way to the tube station, I finally think I understand how deep that fracture really is. The collective fracture feels like the deep twisted root of dysfunction and violent individualism in America. Most Americans of European ancestry don't really acknowledge or even understand how deeply we've been impacted by the rupture and our connections to ancestral homes. Were not taught the history of enclosures and severe religious persecution and witch hunts and class wars across Europe, in an honest way. We rarely talk about how we took those wounds and spread them out onto the Native people of America once our ancestors arrived, or about how many of our ancestors stole and enslaved and sometimes murdered people from other lands in an evil attempt to gain power and wealth and status. The unacknowledged pains and ruptures result in cultural appropriation, white supremacy, classism, bootstrap mentality, and an extractive view of everything around us.

Dani:

I longed to learn more about history and migration and colonization and how it plays out and impacts us today. I want to know the songs and foods and plants from the past. I want to know where I come from the mythology of those places to make sense of why I am who I am, and how that informs my place and community.

Dani:

At the same time, I also acknowledge that many people don't know the names and places from which their roots come. There are people exiled from their lands because of colonization, occupation, war and other forms of violence and oppression. Some people never kept written records and shared their knowledge and family names only through oral traditions. That was fractured by colonizers pushing their languages out of them, shoving new languages into their throats.

Dani:

Many people are treated like outsiders in their own ancestral lands, others still with ancestors who were stolen from their homes, and they have no records to reference. I ponder this all as I continue my tiny pilgrimages. Wonder where I belong. The longer I stay here, the less I'm certain that I want to go home.

Dani:

But I do return to Sonoma County, home of the Pomo, Coast Miwok and Wappo people. California was a promised land that my paternal grandparents arrived in as Dust Bowl refugees in the 1930s. Seeking water and farm work, they traveled around picking fruit at labor camps before settling into Tehama County, the home of the Nomlaqa Winthūn people, where my dad, their eighth child, was born in 1937. And where most of my nine siblings and I were all born and raised over the course of three decades.

Dani:

My grandparents opened a fruit stand in the 1940s that some cousins still operate today. It feels like a huge accomplishment given that they had lived in labor camps just a decade before. My huge family crammed into a small three bedroom house at the end of a dead end road that sat against the edge of acres of prune and walnut orchards, two miles from where my dad grew up. We never had much, just enough to survive and go on one family camping trip a year, before my parents divorce. But my parents worked hard.

Dani:

My dad hammered away at construction jobs. My mom picked strawberries in the summer and sorted walnuts in the fall and early winter before cleaning hotels after the divorce. We grew most of our own food, raised chickens and ducks and hunted and fished. We had deer, pheasants and catfish stacked up in our deep freeze. My mom canned vegetables and blackberry jam in the summer. My dad played his banjo on the front porch and drank cheap canned beer on the weekends in between making never ending repairs to our house.

Dani:

Most folks in our tiny rural community lived in poverty, or just a stitch above it. My parents owned our house and a half acre we grew our vegetables and fruit trees on and we had a little creek that we swam and played and fished in. I now know there was privilege in homeownership, but I think we were the poorest family I knew at the time.

Dani:

The land helped us survive. It provided food and abundance and what we didn't have or grow ourselves. We bought from others in the community. We'd buy big gallons of milk from the church pastor's wife and make homemade butter from the thick cream we skimmed off the top. When the chickens were killed by foxes or other wild animals, we'd buy a dozen eggs for 50 cents from a farmer down the road. Sometimes I'd trade him a can of plump tomato worms for a few extra eggs and watch him feed those worms to his hens.

Dani:

There was little to no talk about how we could give back to the land though. No discussions about what we owed it. Maybe because our ancestors weren't a part of the landscape or history of where we lived. And we didn't have an established relationship with that place. Maybe my family was too busy focusing on getting food on the table. We lived a very simple yet extractive settler lifestyle in that place; taking what we needed to get through one season to the next, burning our garbage and a burn pile when it accumulated, even visiting rural dumps to take usable or antique items when we found them.

Dani:

Still, despite a not great childhood for other reasons, I personally felt very connected to that land. It provided respite from the tension and conflict that outgrew the space in our home. I wandered around alone for hours talking to trees playing make believe with insects that I imagined with fairies, watching muskrats and beavers dunk and dive in the creek. I caught turtles and crawdads and played with them under the hot Valley sun before releasing them back to the creek. I knew where to find bird nests and which side of the blackberry bushes grew the sweetest berries. I knew what time the bats would swoop into the night sky. I knew when to expect the wild boar roaming down from the foothills based on how high the temperatures soared.

Dani:

I've always felt at home in Northern California. The landscape with its redwoods and oak woodlands feels like a part of my DNA. I love the trails I've walked for decades. I love that I have full on relationships with the same patches of nettles and mugwort and elderberry trees that I visit year after year. There's such a comfort when the red tailed hawk screeches overhead and California quail scramble under wild rose bushes. I've also built a human community for myself and my kids, a network of wonderful friends who are changing the world through community organizing and teaching and offering various types of physical, emotional, and spiritual care. They create art and music and books and safe spaces, and protect land and vulnerable people in Sonoma County, where I've lived for 30 years.

Dani:

But upon my return home from the UK, I'm served a notice to move from the home I had rented and raised my two kids on my own. After nearly 20 years, it's a crushing experience thinking about how close I am to being pushed out of the place I love. Sonoma County has become too expensive for many of us to live a comfortable life. By comfortable I mean, not paycheck to paycheck. The cost of housing is completely bonkers. And the lack of housing is dire. We've been in a housing crisis for years and after the devastating 2017 fires that engulfed over 5000 homes. Our housing shortage obviously got worse. A friend that works in real estate recently told me that there are around 5,000 2nd homes, vacation homes owned here too, just sitting here completely empty. Most of the year. Two reports came out recently, one saying that $20 An hour or $41,000 a year is a livable wage. And another stated that an income of $70,000 for a single individual living alone is now considered low income. This is wild, it doesn't add up. Who gets to live here? Who gets to own here? And how much do they get to own? one house? two houses? more?

Dani:

I know that no one is obligated to care for me specifically. But aren't we collectively responsible for keeping those with less from falling through the cracks?

Dani:

A friend offers me her rental cottage deep in the Redwoods not far from the Pacific Ocean, about 30 minutes from where I have lived. It is the only affordable place I can find over the course of two months of seeking. I snatch it up knowing that if I pass it over, I'll be locked out of a place to live in Sonoma County. And we'll need to move away after 30 years to, I have no idea where. The cottage is small and cozy with a big Redwood rings circling one corner and acres of forest and creeks and even a waterfall stretching out behind it. A fox sometimes visits my back porch peering through the door at me and my cats. Ravens and deer are the neighbor's I will see the most. I hear owls at night. Raccoons sometimes sneak into my house and eat whatever they can find, if I leave my door open while I'm out.

Dani:

The first fall and winter in the cottage, my health plunges. I struggle with hauling small loads of firewood in my car, keeping my house warm, keeping my spirits up, keeping up on work deadlines and the classes I teach. To make it through, I tell myself I am now an official woodland witch, and romanticize the atmospheric river storms and the trees falling and the power outages that first winter. I read books with light from my headlamp.

Dani:

The forest is beautiful, but living alone in this forest is incredibly isolating. I feel cut off from my network, my community, my sense of belonging. I tried to sink deeper into my connection and the history here to the tales that were spoken under these trees while my people were still across the Atlantic. I think about the generations of people before me who got displaced, were forced to flee or had the chance to start over on lands that they believed would bring more opportunities.

Dani:

I half joked with my kids that now that my ancestors are all healed up, maybe they're trying to pull me back to Scotland or Wales. That I should indeed try to move abroad now that I'm an empty nester with the ability to work mostly remotely.

Dani:

I drive to visit a friend on a farm and cultural center where he lives. I talked to him about my move about my only slightly kidding existential slash midlife crisis. I tell him all about my trip, about my mind being repeatedly blown by my experiences there. We laugh about ghosts lurking in museums haunting the curators. This friend is Pomo, one of the Indigenous people in this part of California, and he listens to me as I describe some of my more surreal experiences in Scotland and Wales. The history of imperialism there against the Scottish, the resistance against the British through the Welsh speaking their own language, how I felt a deep sense of belonging, knowing that my ancestors were buried all over that island for 1000s of years. He reminds me that this is how Native American people feel, every day. They have the living connection to the land I feel a hunger for. He comments that maybe if more people visited their ancestral homes, or at least learned about them, they'd understand how Indigenous people feel, and have some empathy about colonization.

Dani:

Navigating the feelings of deserving access to affordable housing as a low income person, and someone who gives what she can to the community as a lifelong Californian. And the questions of, do I even belong here? Maybe I should repatriate to a country where I've never actually lived is complicated.

Dani:

The longing for connection in and to both of these places feels urgent. But I'm not culturally Scottish or Welsh or Irish. So I wouldn't quite fit in there either. But I love those places. Not because I feel that the land or culture are better than others, even though I should add that the national animal of Scotland is a unicorn. But because for better or worse, they're a part of my history. The same as living in America, for better and worse. It's a part of who I am.

Dani:

But of course, it's easy to romanticize moving to a country I've only visited. Yes, there's better health care, less mass shootings, free access to museums, but they have their problems too... Brexit, anyone? And of course, there's a whole global imperialism situation. And on a more personal level, I also know what terrible things many of the men and my Scottish ancestry in particular did. I know the suffering they caused. I know that most of the women in this line were married off by those men. They were like gold pieces used to secure land, to build alliances with other Clans to offer peace to gain power and security.

Dani:

I mostly know who exploited. I know who the victims were. I know who came to America as indentured servants who were fleeing or exiled, and who came with money in their pockets. I don't know their individual feelings if any of them were content with their lives. But scrolling through the family records, I've found and studying the history of feuds and battles and territories brings at least some of it to light. The further I venture into my own ancestral history, though, the more clouded and complicated and wild it is.

Dani:

Connecting with my ancestors and the deep history and traditions of my people can certainly appear to be yet another form of spiritual bypassing. But I don't experience that way. For me, it's a form of spiritual accountability of spiritual responsibility. I can't undo what they've done or what was done to them. But I can certainly live my life in a way that both honors the best parts of them with their hopes and dreams for better lives for their descendants, and in a way that does better than the worst in them.

Dani:

Maybe a sense of belonging comes from just that: understanding our past and the past of our people, and doing better.

Dani:

I'm still sifting through my ideas about it all as I continue living on stolen land, perpetually renting and a place that my ancestors took for their own, and where I'll never have the resources to buy a piece of it for myself. But again, I do deeply love Northern California. But my mind constantly wanders back to the old country, to another time when that connection to place was mostly unbroken. There's something about taking step after step on the ground where my ancestors had lived and died for 1000s of years. That really rattled me.

Dani:

Breathing in the scent of the Scots Pine and the crisp air pushing in from the North Sea, seeing the same stones standing out on the land for generations to speak into the communities mythology, hearing the old languages. It left me with more questions and answers. I felt the same after leaving Ireland on a different trip. I cried and cried from a sense of nostalgia for a place I had never lived.

Dani:

Back in the UK during my final weeks there, I head to Wales and visit the Abbey ruins of a place where some of my Irish ancestors happened to be buried. The bodies of these two women were put there before grave markers were used, so no one knows for sure under which section of soil their bones are resting. I wander the grounds after an early springtime rain clears. I leave Irish whiskey bottles in the bushes for them, and whisper their names with clumsy pronunciation, like I had done with so many of my people over the past two months. I feel like a weird ghoul creeping around like this, but I know they'll be grateful for the offerings. I imagine them laughing, quenching their thirst, winking at me. I pick wildflowers and small unfurling ferns from the burial site, imagining their bodies feeding the floor above their graves. Through the flowers I pick, I imagine a direct transmitted connection to the dead below the surface and back through time, and I feel like I'm home.

carla:

Thanks for listening to On Belonging. This episode featured Dani Burlison with music by Zf Bergman

Jamie-Leigh:

On Belonging is curated by carla joy bergman and Jamie-Leigh Gonzales, with tech support by Chris Bergman. The show's awesome theme music is by AwareNess On Belonging is a Joyful Threads and Grounded Futures creation. Please visit groundedfutures.com for show notes, transcripts, and to read more about On Belonging.

carla:

Till next time, keep walking. Keep listening.

*

These transcripts were generated in Otter, and lightly edited by our team.