Shownotes

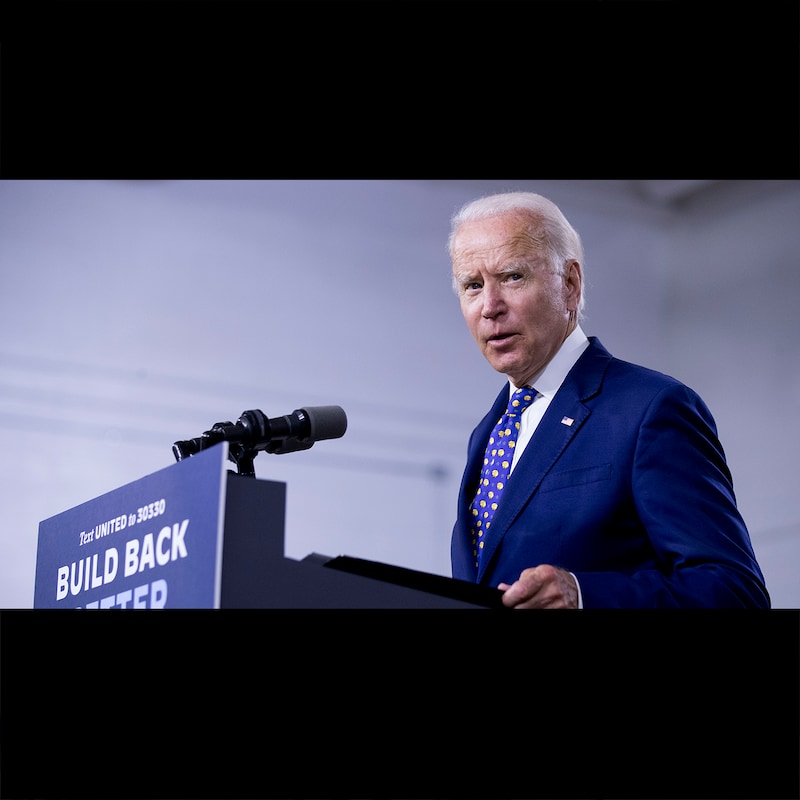

On November 16, a $1 trillion infrastructure bill was signed into law by President Biden, marking the biggest investment in the country’s infrastructure in decades. At the same time, an even larger social spending bill sits in a state of limbo in Congress, with no resolution in sight.

What happens in the US Congress over the next few months should matter to everyone, not just the political hobbyists. With proposed government spending on everything from fighting climate change to supporting new industries in the US, the success or failure of President Biden’s legislative agenda will have a huge effect not just in America, but around the world.

On this episode Sarah Baldwin ’87 and Dan Richards talk with two experts to get a sense of how President Biden’s agenda has been making its way through Congress, and how the process fits into the bigger picture of US electoral politics.

Guests:

Carrie Nordlund is assistant dean for undergraduate programs at Brown University, and co-host, with Mark Blyth, of the (aptly titled) podcast, Mark and Carrie.

Wendy Schiller is a professor of political science at Brown and director of the Taubman Center for American Politics and Policy, which is housed at the Watson Institute.

Learn more about the Taubman Center for American Politics and Policy.

Learn more about Watson’s other podcasts, including Mark and Carrie.

Transcripts

[MUSIC PLAYING] SARAH BALDWIN: From the Watson Institute at Brown University, this is Trending Globally. I'm Sarah Baldwin.

DAN RICHARDS: And I'm Dan Richards.

SARAH BALDWIN: So it's been a busy few weeks in the US Congress.

REPORTER: Overnight, the House passing that trillion-dollar infrastructure bill, Democrats working late into the night to reach a deal after months of delays.

DAN RICHARDS: A massive bipartisan infrastructure bill was signed into law.

SARAH BALDWIN: And an even more massive social spending bill is stuck in limbo.

REPORTER: After weeks of negotiations, missed deadlines, two trips by President Biden to Capitol Hill--

REPORTER: The Democrats' social spending plan still a bit of a work in progress.

DAN RICHARDS: And meanwhile, there were these special elections around the country a few weeks ago that have gotten a lot of people wondering if the Democrats will be rewarded or punished for their ambitious agenda come next year's midterms.

REPORTER: Virginians have a new governor-elect. ABC News has projected Republican Glenn Youngkin as the winner.

REPORTER: President Biden tonight acknowledging that voters in Virginia and New Jersey sent a loud message to the Democratic Party.

JOE BIDEN: People want us to get things done.

REPORTER: It's a stunning defeat for Democrats, by the way, in a state that President Biden won by 10 points just a year ago.

SARAH BALDWIN: Now, breathless political news like this should definitely be taken with a grain of salt, always. But at the same time, President Biden's domestic agenda is one of the most ambitious we've seen in this country in half a century.

DAN RICHARDS: And with proposed spending on everything from fighting climate change to reducing inequality to supporting new industry in the US, these bills will have a huge effect, not just in America, but around the world.

SARAH BALDWIN: On this episode, we're going to both zoom in and take a step back to try to get a better understanding of, A, what's been going on in the US Congress these past few weeks--

DAN RICHARDS: And B, how it all fits into the bigger picture of US politics right now.

SARAH BALDWIN: We spoke with two experts on the subject. Cory Nordlund is Assistant Dean for Undergraduate Programs at Brown University, and co-host with Mark Blyth of the aptly titled podcast Mark and Carrie.

DAN RICHARDS: And Wendy Schiller is a professor of political science at Brown University and director of the Taubman Center for American Politics and Policy, which is housed at the Watson Institute.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

So Sarah, you talked with Carrie Nordlund first. What did you get into with Carrie?

SARAH BALDWIN: I wanted to talk with Carrie to get some clarity on Biden's agenda. What does he want to spend money on, and why? And how are members of Congress reacting?

Carrie, thank you so much for coming on Trending Globally.

CARRIE NORDLUND: Thank you for having me, Sarah. I'm so happy to be here in person, seeing you.

SARAH BALDWIN: So I wanted to talk today about Biden's--

As Carrie explained, this infrastructure bill that recently passed is just one of three bills Biden's been promising the American people. Here's Carrie.

CARRIE NORDLUND: --and the first thing that he started when he came in were the checks that many Americans received. And this was COVID relief. And it was pretty bipartisan. And families received and Americans received, in general, x amount of dollars. And I should probably the specifics on that, but I can't remember it because it seems so long ago now. But that was the first act that the Biden administration implemented.

The second one is the one that has been with us probably since February of this year. And that is the bipartisan infrastructure framework, or BIF, which really suggests that they need a little bit of help on messaging. But this is the hard infrastructure bill. So this was rail and waterways and bridges and classic road, potholes, like all of that sort of stuff. And it really starts with the ambitious $2.5 trillion proposal. The Republicans came in with a similar bill, because I think, on the content of it, there's a lot of agreement between Republicans and Democrats, but much smaller in terms of the total number. And theirs was about 800 billion, which is still a boatload of money, but as compared to what 2 and 1/2 trillion, I guess there's a lot of difference between that.

But at the same time the newly elected Biden, President Biden puts out this hard infrastructure bill, then you might also remember he puts out what they called soft infrastructure or human infrastructure bill. So this is like pre-K, this is paid family leave, this is--

SARAH BALDWIN: Expanded Medicare.

CARRIE NORDLUND: Yeah, exactly. Like Bernie Sanders' dental and vision stuff. So all of this stuff that's more on the human side of things. And so these two bills become pretty linked together, at least legislatively, for a lot of elected officials.

SARAH BALDWIN: Do you think it's fair to compare what Biden is attempting, then, to the New Deal?

CARRIE NORDLUND: I think that's totally accurate, yeah. And in some ways, I mean, if he gets the second-- the third bill, sorry, the third bill-- passed, it will be on par with that.

SARAH BALDWIN: Wow. And the first bill passed.

CARRIE NORDLUND: First bill gets passed, right. Checks get cut. Yep.

SARAH BALDWIN: Why did the second bill take so long? Was it the cost? Was it corporate interests? What slowed it down?

CARRIE NORDLUND: This is going to shock you. Politics.

SARAH BALDWIN: No.

CARRIE NORDLUND: Right? I know. Right. Because I think you're right, I think yes to all of the things that you just listed, but I mean, in general, there's an agreement, yes, we need to upgrade all of our bridges and all of that sort of stuff. But it became then the Republicans went back to we don't want to have a huge deficit, this bill is going to run the deficit up, classic Republican talking point. But also, I think, slightly different was that, within the Democratic caucus, there's a lot of tension.

So there's a tension between the moderates and the quote unquote progressives. And there's, I don't know, maybe 20 to 25 progressives in the House. But the Senate is much more moderate on the Democratic side. So you have the Joe Manchin and the Kyrsten Sinema. And those two parts of the Democratic Party just are not seeing eye to eye. And the Republicans were smart because they just kind of sat back and let the Democrats duke it out with each other.

SARAH BALDWIN: Why was it so hard? What was taking so long?

CARRIE NORDLUND: I think the mainstream media would say that the progressives in the House held the bill hostage, because they essentially said to Speaker Pelosi, and I think a little bit to President Biden, too-- there was a great sort of behind-the-scenes piece in the New Yorker from a few days ago-- that they were like, we're not going to vote on the hard infrastructure unless we know there's going to be a vote on the human infrastructure side of things. So I mean, I think it's probably a little bit too harsh to say they held it hostage, but they weren't playing around.

SARAH BALDWIN: Using leverage.

CARRIE NORDLUND: Yes, using leverage. And they were serious, as well, to say, Mr. President, our voters are the voters that put you into office, so we're not going to just play around and do this for symbolic reasons. We want a seat at the table, and we really want to be part of the negotiation. So big holdup is just that ever-growing tension between those two parts of the Democratic Party.

SARAH BALDWIN: And what pushed it across the finish line?

CARRIE NORDLUND: Well, again, politics. So you had the off-year election cycle, and you had a very close race for the New Jersey governor, right? And at one point, the Democrat, the incumbent looked like he was going to lose. And then you have a Republican beat the Democrat in Virginia. And I think that that then provided leverage for the White House to say, you know, this is setting us up for just a terrible midterm, so we've got to get our stuff together. And so Pelosi calls a vote, I mean, I think within hours after they start to see those election returns come in.

So they vote on that the 5th of November. And so the second part of the three-part package from the administration passes. So it's still new. It's still new.

SARAH BALDWIN: Absolutely.

CARRIE NORDLUND: And then we're hanging on to see what's happening with the human infrastructure bill. Pelosi would like to schedule a vote in the next couple of weeks. The Senate hasn't passed a version and the House hasn't passed a version, so it has to get through both chambers. This is likely going to be voted on in the Senate through reconciliation, so just a simple majority. So it makes it filibuster-proof. And the House still then has to do their dance. I mean, Speaker Pelosi still has to do her dance to get the progressives on board to vote on the bill.

SARAH BALDWIN: And what do you think she can use to entice them to do that?

CARRIE NORDLUND: I think it's probably a little bit of what got them moving even a week ago, is that things are hanging in the balance and do you want Trump presidency part two, because that's where the train's going right now.

SARAH BALDWIN: And some bill is better than no bill.

CARRIE NORDLUND: Yeah, yeah, exactly. Yeah.

SARAH BALDWIN: I find that I'm often flummoxed that people kind of have this what has the government done for me lately attitude. And sometimes, those people are people for whom the government is actually doing a lot. What would it take to change people's perception or conception of the federal government's role in their lives, in safeguarding or enhancing their lives?

CARRIE NORDLUND: So when you and I talked about doing this interview, I thought to myself, I don't actually know what's in that bill. And I think that, in and of itself, is a problem because whoever is in power-- and then, to become partisan about this, I think Republicans are much better around saying simple stuff about what is in this bill. But the White House has not said, you are going to get x amount of dollars for this part of the policy, or you're going to see this thing improve. That kind of stuff I don't think gets communicated very well, that this particular policy is going to help me in a very clear, succinct way.

SARAH BALDWIN: To sort of wrap up about this, Carrie, do you believe that Democrats are going to consider, if the third bill passes--

CARRIE NORDLUND: Yeah.

SARAH BALDWIN: --do you think that the Democrats will believe they have something to celebrate, that they will feel triumphant?

CARRIE NORDLUND: I want to say yes, but probably not because Democrats can never be happy or satisfied for too long, and that all sides will be disappointed, meaning moderates will be disappointed, progressives will be disappointed, rank-and-file Democratic voters will be disappointed. So there'll be a lot of disappointment for the upcoming holiday season to spread around. But I think, just to a point that you just made about the level of spending, I think that should actually be a reason for some glimmer of optimism, because it is a huge-- $3 trillion in spending is a lot of spending. And so yes, it doesn't quite reach where President Biden started with, but it sure does a whole lot that wasn't being done before. And I think that's a reason to be at least not totally down in the dumps about it.

SARAH BALDWIN: So in a way, maybe when all is said and done, it would behoove Democrats to reclaim the narrative and really re-elevate the discourse to being about transformational change and unprecedented investment. Is that what you're saying?

CARRIE NORDLUND: Yes. And then to have one or two bullet points around specific things that are easy to understand, and then repeat that over and over until the midterms in Twenty-Twenty-Two.

SARAH BALDWIN: And what should Republicans do?

CARRIE NORDLUND: They should continue to question the price tag of the bill, and maybe actually just continue to do a little bit of what they've done, which is kind of sit back and let the Democrats just continue to confuse the voters and just have sort of bad communication style. I mean, the Republicans, I think, have been very smart in the way they've played this. Heading into the midterms, I think if they keep Donald Trump off the campaign trail, they're going to be really successful.

SARAH BALDWIN: Well, we will have to see how it all plays out. And I hope you'll come back on and explain it to us when it's happening.

CARRIE NORDLUND: Thanks again.

DAN RICHARDS: Wow. This all sort of reminds me of that saying, a good compromise is one way where no one is happy.

SARAH BALDWIN: Yeah. But I mean, a lot of what the Democrats wanted is in this infrastructure bill, compromises and all. And a lot of what they're struggling with right now is actually messaging.

DAN RICHARDS: It's interesting you bring that up because when I talked with Wendy Schiller, that issue came up a lot, as well.

SARAH BALDWIN: In what ways?

DAN RICHARDS: Well, in a few ways, actually. It sort of came up in my first question for her, which was vaccination rates are going up, the unemployment rate is going down, a huge bipartisan bill was just passed-- so why is President Biden's approval rating at an all-time low? And here's what Wendy said.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

WENDY SCHILLER: President Biden's approval ratings are low for two main reasons. One is deep, pent-up frustration amongst, I think, all Americans about what they've endured in the last year and a half of the pandemic, particularly parents with children, in terms of going to school or home schooling, and loss of jobs, loss of income, not to mention, of course, all the loss of life associated with COVID. And restrictions vary everywhere. It's really complicated to figure out what you have to do and whether you have to wear a mask. And the frustration that builds over such a long period of time, people want to take it out on somebody. And they're going to take it out on President Biden.

The second reason his approval ratings are so low is that he and the Democratic Party overpromised. They overpromised and they've under-delivered. They said, well, we have the government back, we're the Democrats, and we're going to not just repay our core constituencies, but give working families and Americans a lot of the tools they need to be successful. And certainly, COVID has interrupted that.

But the disagreement within the Democratic Party, particularly in the House, stalling infrastructure for a couple of months and not being able to agree on a very large social welfare spending bill that has not been explained to the American people at all, nobody knows what's in it, nobody knows why we have to pass it. So it's been what I call messaging malpractice on the part of the Democrats. And no matter what you do and produce, if you cannot sell it, you're going to get voted out of office.

DAN RICHARDS: Well, speaking of messaging and overpromising on the part of Democrats who are in control of Congress, this tension that's been happening in negotiating this social spending bill, how much do you see that as it's just the reality of what happens when there's a Congress with an incredibly slim majority versus are there certain groups that you think have really been kind of committing errors in the process of bringing this through?

WENDY SCHILLER: I think this version of what you could deem the Democrats' social spending bill is reminiscent of other efforts the Democrats have made when they've captured office from the Republicans. So Bill Clinton comes in, gets elected in Nineteen-Ninety-Two and takes office in '93, and he passes a criminal justice reform bill and gets defeated by members of his own party, actually, in the first version of the bill, and takes a couple more months. This is a lesson to Biden. And Joe Biden was the author of that bill, so he remembers this. By the end of the first year of the Clinton presidency, couldn't get this crime bill passed. He had to wait until the second year.

And if you go flash forward to Obamacare, and President Obama is addressing the economy, obviously, when he came in Two-Thousand-Nine but as a component of the economy with such massive job loss, millions of jobs lost, you had to find a way to have people have health care insurance. So he passes it, but they don't explain it. And so the Republicans take hold. They basically run with the fact that this is a bill that can be punctured in terms of public messaging. And they are very successful in Twenty-Ten.

And now, again, we have a scenario where the Democrats are offering the American people, but not selling to the American people, programs that they claim will help them, that are good for the vast majority of people, but nobody understands what they are and why they need them. So it's the third time you've seen Democrats do this in 20 years-- almost 30 years, actually-- and you wonder, how is it that Joe Biden, who was there for the first time in the Senate, certainly there for the second time as vice president, doesn't remember that lesson now that he's president?

DAN RICHARDS: How much is this a error that keeps getting made, though? And is it also partially just like almost like a law of physics that a president comes in, even if they have both houses of Congress, and they're just going to do something, and it's going to be easier to make them sort of the villains of whatever new project and switch them out in the midterms?

WENDY SCHILLER: I think the Democrats are worse at this than the Republicans in the visibility of conflict, but they're better, in the end, getting the legislation passed because Democrats are vested in government efficiency and government effectiveness and programs. They want to do more at the federal level. Republicans don't always want to do more at the federal level.

But if you look at the Bush presidency even before 9/11, he passed his big tax cuts before that happened, and then, of course, after 9/11. But he also passed the Medicare prescription drug bill, which expanded Medicare prescription drug coverage for seniors. He got that through, and that was a tough-- people forget that was a very tough vote. There was a lot of strong arming on the floor of the House among Republicans at that time.

So I think, Dan, you're pointing to something that's so crucial in presidential-congressional relations, which is that members of Congress do not always see their electoral fate tied to the president's because they are elected every two years in the House and every six in the Senate. And of course, only a third of the Senate is ever up for reelection at the same time. So basically, the president doesn't have a lot of political capital to wield, whether it's Republican or Democrat.

DAN RICHARDS: I want to turn now to the social spending bill itself. Do you think it would be more popular, both with American voters and in Congress, if it focused on just one issue, like health care, education, or climate, as opposed to what it is now, which seems like it's partially funding a lot of different things, from broadband access to prescription drug pricing?

WENDY SCHILLER: Well, one of the key, foundational elements of this what we call reconciliation bill is that it has a lot to do with the tax code. And when they enacted the reconciliation procedure and they started to use it in the early Nineteen-Eighties, they actually put in this filibuster-proof 50-vote margin, that if you get 50 or 51 votes, you can pass changes to the tax code, as well as entitlement programs, things like Medicare, social security, social security disability, for example. So you need to use reconciliation so you don't need 60 votes, but you need-- typically, for it to be appropriate in reconciliation, it has to change the tax code.

So you want to do it all at once because if you're going to balance the revenues and outlays and you're going to make changes to taxes, whether it's tax credits for families with children or tax credits for carbon-neutral emissions, you want to do it all at once because it all goes together, in terms of the impact on the budget. And so that's the idea. You know, Ronald Reagan had a lot of reconciliation bills that he passed in a single year in Nineteen-Eighty-One.

DAN RICHARDS: I didn't know that.

WENDY SCHILLER: You're not supposed to be able to pass more than one--

DAN RICHARDS: Right, I thought--

WENDY SCHILLER: --big one in a year.

DAN RICHARDS: --it was a one-year.

WENDY SCHILLER: But he did manage to do that, basically. It's pretty interesting how he managed to do that. But technically, you're not supposed to. And I think they've been more adamant about that in the last 20 years than prior. So that's the reason they have to put it all together. But you could argue they could pass one next year. They could do climate change next year. Presidential administrations don't like to do that because members of Congress are running for re-election, but in this case, the Democrats, it would make them look better if they actually passed more things in an election year and to deliver to their constituents than to bury it all in December and then have nothing to talk about for the entire year next year.

DAN RICHARDS: Do you think there's a possibility that that's a strategy that's really happening right now, and we're getting some sort of theater that this is the last moment for everything, and people behind some leather padded room are like, oh no, we're going to do another thing in six months?

WENDY SCHILLER: I think that it's a reasonable conversation the president can have with members of Congress. The idea is, well, if we tell them it's the only chance, then they'll vote for whatever we give them. But the progressives, particularly the very core group of progressives, which has shrunk quite a bit in the last couple of weeks, they won't budge. And they're not falling for it. They sort of understand what this is all about. But whether it passes now or it passes later, you still have to persuade Americans that they want it. And the Republicans have really gotten out the door quickly in labeling and demonizing this package, just as they did with Bill Clinton's health care and, of course, Obamacare. Then you're stuck undoing that. Then you're really battling on that. And that's really difficult to do.

You know, gas prices always seem to go up over the holidays-- Memorial Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas. And a lot of Americans believe it's basically a conspiracy by the gas companies just to raise prices. So I'm not sure gas prices is going to be a great long-term issue for the Republicans. But inflation has typically been a Republican issue, tackling inflation, because Republicans have typically been the party of the wealthy. What's interesting now is their messaging is not about this is going to erode your savings or your assets over time to the wealthy, but to the working class, who don't make a lot of money, who are paying a lot more for milk, bread, and eggs, to use stereotype. So that, to me, is the really fascinating element of Republican Party platform Twenty-Twenty-One.

DAN RICHARDS: If you were the sort of overarching consultant for the Democratic Party right now, there's lots of anxiety in a lot of directions within that party. What would you recommend for them for the next 10 months, to get them on a better footing for the midterm elections?

WENDY SCHILLER: The big Achilles heel for the Republicans, I would argue, among suburban voters is Donald Trump. He'll mobilize the base, but I think if he's too closely tied to their congressional challengers, particularly in Senate races, I see that as a difficulty for him among the very same suburban voters that may have voted for Glenn Youngkin. They're not going to vote for somebody who is constantly photographed with Donald Trump, which is why Youngkin wouldn't do it.

And that's the unknown for the Democrats. You know, will the Trump-supported candidates win primaries and be the Republican opposition, or will Trump recalibrate and start to endorse, even if his endorsement's not welcome, endorse more moderate versions of Republicans so that he can look like he's helping them win and not be politically toxic to them? This is going to be fascinating to see how this all plays out in the primaries in the Republican Party.

DAN RICHARDS: And in the meantime, as well, for the Democrats, as you said, to make sure people know what's in all the bills they have been trying to pass, and maybe will have passed by the time people listen to this.

WENDY SCHILLER: Yeah, Ohio Senate candidate Tim Ryan, who's a current member of the House from Ohio, has a great Twitter message, very clear, that says, this is what we just did. This is how much money. And then, of course, as soon as he figures out how much Ohio will be getting or if there's particular projects in Ohio, they will be repeating it over and over and over again. You know, never underestimate the power of repetition in politics.

DAN RICHARDS: Wendy, thank you so much for coming back to talk with us on Trending Globally.

WENDY SCHILLER: It's always fun. Thanks.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

SARAH BALDWIN: Hard to believe how close the next election feels already when you hear stuff like that.

DAN RICHARDS: True. But also, as Wendy or any other expert will make clear, we really have no idea where the country will be by the time of the midterm elections next fall. And there's a more important issue at stake, more important than just who might win what elections in the near future. And it's that the more that people understand what is in Biden's agenda and what are in these bills in Congress, the more voters can hold elected officials to account, which is good for everyone, except maybe for some elected officials.

SARAH BALDWIN: True. And on that note, we hope hearing from Carrie and Wendy will help you feel a little less bewildered and frustrated next time you read about chaos, gridlock, or bad blood in Congress.

DAN RICHARDS: Which, let's be honest, will be soon.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

SARAH BALDWIN: This episode was produced by Dan Richards and Kate Dario. Our theme music is by Henry Bloomfield. Additional music by the Blue Dot Sessions. I'm Sarah Baldwin.

You can learn more about the Watson Institute's other podcasts on our website. We'll put a link to it in the show notes. And if you haven't already, please leave us a rating and review on Apple Podcasts. It really helps others find us. We'll be back in two weeks with another episode of Trending Globally. Thanks for listening.

[MUSIC PLAYING]