Shownotes

Sam Yuen

Sam Yuen is one of the larger-than-life characters that drive the historical narrative of the LA Chinatown massacre. Historical sources paint a picture of a laconic, stoic-minded business leader whose traditional methods and lack of adaptability made him and his company vulnerable to disruption.

Sam Yuen was the leader of a conservative faction who thought that the Chinese community should restrict its contact with outsiders as much as possible. They were willing to provide services to wealthy non-Chinese residents of the surrounding area, but they did not go into business with people of different backgrounds. It was this attitude against which the upstart, Yo Hing was rebelling when he split off from the original Sze Yup company. By collaborating with wealthier and more influential Anglo and Latino business partners, Yo Hing aimed to fundamentally change the structure of Chinatown’s economic system. Traditionalists like Sam Yuen saw this as excessively risky. Tying up their money in joint ventures with “Gwailo,” who could turn on them at any moment was a grave cause for concern among the traditionalists, who were badly traumatized by the ethnic and political conflicts which had torn apart Qing Dynasty China.

Though he rarely spoke to the press, Sam Yuen was influential enough that certain aspects of his personality come down to us. He was indicted for fist fighting with Yo Hing on multiple occasions, though other than that, his criminal record seems to have been relatively clean. In one particularly famous incident, Sam Yuen managed to get several of Yo Hing’s associates jailed for the egregious maltreatment of an enslaved Chinese prostitute, who was working for them. Yo Hing’s actions in the case of Yut Ho and Lee Yong were probably partially motivated by a desire to retaliate.

Sam Yuen’s most famous quotation was given in an interview with the Los Angeles Star newspaper: “That brave fellow Yo Hing will be killed by those he has insulted and maligned.” Sam Yuen endeavored to make good on this public threat. Clearly, he was not averse to using force or violence in order to get his way. He was also a dangerous man with a six-shooter, as we shall see.

Information about the historical Sam Yuen can be found in Scott Zsech’s wonderful book, The Chinatown War, which also contains a fantastic bibliography that can be used to locate primary sources.

Micah’s personal spin on Sam Yuen is to play up certain aspects of a socially conservative strain, which exists in Chinese culture. This style of relating to the world is a vestige of a militaristic outlook, which was instrumental in securing and retaining power under feudal, imperial rule. Like American masculine culture of the early 20th century, Qing dynasty “conservatives” were preoccupied with physical and mental strength above all things. This preoccupation was paired with a meritocratic belief that the strongest had a natural right to rule over everybody else. In China, this type of outlook was severely impacted by contact with the West, whose superior military technology took away the title of strongest from the warrior class who had held it for millennia. This led to an obtusely anachronistic pride in hand-to-hand fighting skills, which persists to this day as a negative stereotype about Chinese and East Asian men. For this reason, Micah wrote Sam Yuen as a practitioner of external martial arts in Blood on Gold Mountain.

If you have questions, thoughts, your own family stories, or historical context to share, please send us a message at @bloodongoldmountain on Facebook or Instagram.

-----

Blood on Gold Mountain is brought to you by The Holmes Performing Arts Fund of The Claremont Colleges, The Pacific Basin Institute of Pomona College, The Office of Public Events and Community Programs at Scripps College, The Scripps College Music Department, The Entrepreneurial Musicianship Department at The New England Conservatory, and our Patreon patrons.

Blood on Gold Mountain was written and produced by Yan-Jie Micah Huang, narrated by Hao Huang, introduced by Emma Gies, and features music composed by Micah Huang and performed by Micah Huang and Emma Gies. A special thanks to Hao Huang for piano wizardry, Kusuma Tri Saputro for the amazing artwork, Sheila Kolesaire for her critical PR guidance, Muqi Li for her brilliant guzheng playing, Rachel Huang for her editing prowess, and Evo Terra from Simpler Media Productions for his immense expertise and support.

-----

More details at bloodongoldmountain.com

Transcripts

Previously on Blood on Gold Mountain: Yut Ho found life in Chinatown scary and confusing. For answers, she turned to Lee Yong, the young man employed as chef and housekeeper for her and Hing Sing. From Lee Yong, Yut Ho learned how she was a pawn in a gang war that threatened the very existence of Chinatown. In order to ensure her safety, she must play into the twisted politics of the power struggle between rival gangsters Sam Yuen and Yo Hing. At first, Yut Ho was suspicious and hostile, but she soon came to like Lee Yong, who impressed her with his easygoing confidence, and reassured her with his openness and honesty. Now the two of them have the chance to get to know each other better, but it won’t be long before Yut Ho is forced to step into her role as Chinatown’s newest public figure.

Hao:It took a while for Yut Ho to extract the rest of Lee Yong’s story.

He insisted that it wasn’t shame that kept him from speaking freely, but habit. “This is a frontier town,” he told her. “Most people came here from somewhere else. They don’t talk about who they used to be, and they don’t ask questions. Everybody has their secrets.”

“If that’s the case, then why did you tell me about your mother?” Yut Ho demanded.

Lee Yong looked at her. “I don’t know.” he said.

By way of encouragement, Yut Ho told him all about her own past. Lee Yong listened with fascination. He made her describe everything about the village where she grew up, from the mundane details of rice farming to the stories and legends she had learned as a child. “I’ve heard so much about China,” he told her, “I can see it so clearly, and yet it’s always just beyond my reach.” With shining eyes he listened as she described the stark beauty of cranes in flight, and told strange tales about dragons who were rivers, and a monkey who was a king.

Eventually, Lee Yong began to open up.

His parents had come from two different villages, both of which were destroyed in the Opium War. They found their way to Gold Mountain, each following their own path, and both of them ended up in San Francisco. “I think they must have been some of the first Chinese people to come to this land,” he told Yut Ho, “but I’m not sure. They didn’t like to talk about the bad times.”

All Lee Yong knew were the facts. His mother had come to Gold Mountain with a Gwailo man who she thought she could trust. When they arrived, he sold her to a Chinese thug who pimped her and two other girls out of a tiny, lean-to shack. San Francisco’s nascent Chinatown was a squalid slum into which an ever-increasing number of immigrants and refugees were packed. One of the new arrivals was Lee Yong’s father. Unlike the migrant laborers who came to support families back home, Lee Yong’s father was a young man who had lost everything in the war, and was trying to pick up the pieces. He started off as a client, but Lee Yong’s mother liked his smile and his quiet strength. In time, that liking blossomed into a secret love, and they began plotting their escape.

One day they pooled their money and bought a bottle of Baijiu; a foul-tasting brew that was stronger than any Gwailo whiskey. Lee Yong’s mother took the bottle home to her shack, where it was promptly requisitioned by her pimp. He proceeded to drink the entire bottle. Eventually he passed out, and Lee Yong’s parents fled together under cover of darkness. They didn’t stop until they came to a place where the mists of San Francisco seemed as far-off and improbable as the turquoise coves and emerald hills of south China. That place was called Los Angeles.

By the time the Sze Yup Company’s autumn banquet came around, Yut Ho was feeling confident. So far, Hing Sing had upheld his side of their bargain. He treated her like a guest or neighbor, smiling vacantly when he saw her and asking whether she was comfortable. At first Yut Ho was tense in his presence, but she soon realized that he bore her no ill will. When she asked for extra blankets and seasonal fruits, he had them brought to her right away. Lee Yong was right: Hing Sing wasn’t so bad, after all.

During the day while Hing Sing wasn’t around, Yut Ho wrote poems, did exercises, and chatted with Lee Yong. To save time, she would help out with various tasks around the house and then the two of them would sit and talk for hours over endless cups of tea. Lee Yong was easygoing and innocent in a way that brought out those same qualities in Yut Ho. After all, he had lived his entire life in Gold Mountain, and had never experienced the horrors of famine or war. Both Yut Ho and Lee Yong were orphans–his parents had died young–but in spite of that and the day-to-day struggles of life in Chinatown, Lee Yong’s world was stable and fully intact. This wholeness gave Yut Ho comfort and helped her relax. Nothing could erase the trauma and pain of what she had been through during the war, and nothing could bring back what she had lost, but with Lee Yong, Yut Ho finally felt like herself again.

The night of the banquet, she chose a fitted silk Cheongsam of brilliant red. It was traced all over with spidery black embroidery, and in the flickering light of her oil lamp, the pattern blended with layers of shadow to make her look like something out of a legend or a dream. Hing Sing was late. As she waited for him in the dining room, she examined her reflection in the darkened window. I wish Lee Yong could see me like this, she thought.

Hing Sing finally arrived, along with a couple of large, frowning men whom Yut Ho did not recognize. She followed them downstairs, through a dark corridor and out into the alley, where a carriage was waiting. One after another, they climbed in. The whole thing felt slightly surreal to Yut Ho, who had not left her apartment since the day she arrived. It was as though she were a celestial being, who had fallen to earth and was venturing out for the first time.

“So, my ah, little flower,” said Hing Sing with a slightly apologetic smile, “are you ready to dazzle the best and brightest of Chinatown with your radiant beauty?” He seemed to think that the whole thing was some kind of joke. Yut Ho wondered if he had been smoking opium again. “As long as I don’t have to talk, I’ll be fine,” she said. Hing Sing nodded. “That shouldn’t be any problem,” he said. “The men will be too polite to speak to you unless you speak to them first.” “I won’t,” Yut Ho told him flatly. “Are there going to be any other women there?” Hing Sing shook his head. “You’ll be the only one. Sam Yuen insisted.”

The ride was over in a couple of minutes, and they climbed down into the darkened street. Yut Ho barely caught a glimpse of an unfamiliar building before being hustled inside. She found herself in a long, low, room full of paper lanterns which covered everything in a dull red glow. In lieu of windows, the walls were hung with moth-eaten tapestries that might once have depicted scenes from Chinese mythology, or bourne optimistic slogans. Now their threads were coming loose, and all they conveyed was a sense of hard-bitten frugality.

The room was full of men, sitting around tables and talking quietly. Yut Ho counted about thirty of them as she followed Hing Sing to a long, cloth covered table, which stood on a low dais set against the rear wall. She was immediately struck by the lack of noise; back home in Sze Yup, a group this size would be laughing, joking and raising a racket fit to wake the dead. These men seemed half dead themselves. They sipped their tea and murmured in ghostly voices, glancing across the room from time to time as though they were conscious of being watched, or of being hunted. As she took her seat, Yut Ho felt an unexpected sense of disappointment. Was this the banquet she had been preparing for? It felt more like a prisoners’ mess, or a funeral. She wondered if Yo Hing’s Company gatherings were more lively.

All of a sudden, a hush came over the room. One by one, the men turned their heads toward the door, and Yut Ho felt an unpleasant prickling on the back of her neck. Then a man stepped through the door, and she knew in an instant that this was Sam Yuen.

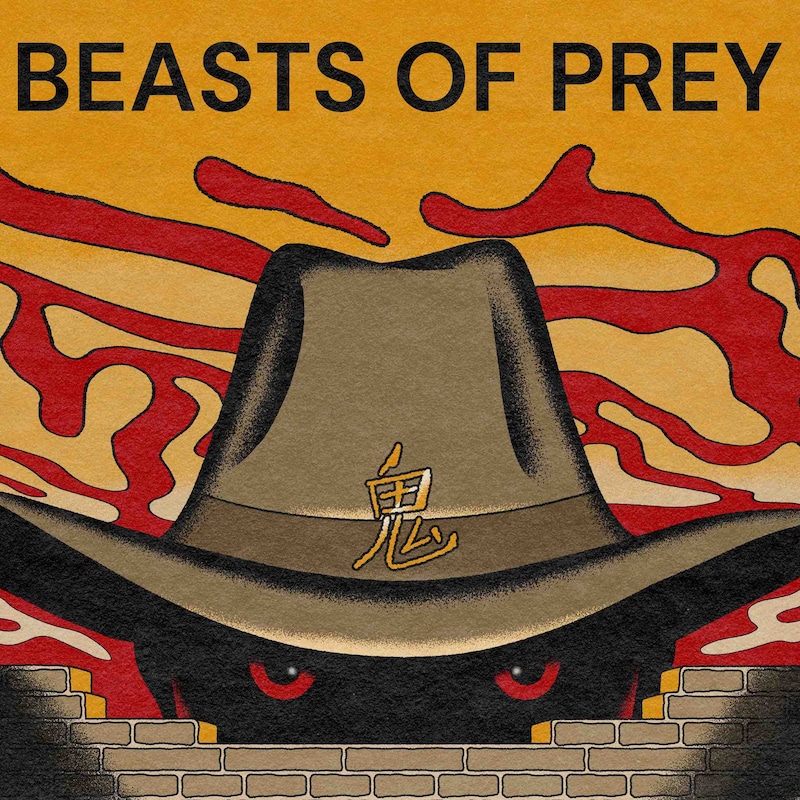

He was much smaller than Yut Ho had imagined. Short and wiry, he looked half the size of Ah Choy or Yo Hing, but he radiated an air of casual menace, like a beast of prey. The flat brim of his Gwailo hat cast a shadow over his eyes, and the sound of his heavy boots cut through the silence as he stalked across the hardwood floor. Hing Sing pulled out a chair and stood behind it, his head bobbing atop his tall, stooped form. Sam Yuen sat. There was a moment of dead silence.

Hing Sing stepped forward, and cleared his throat. “Ahem. Valued members of the Sze Yup company. It is with great pleasure that I welcome you to our autumn banquet. Now is the time for us to celebrate the successes of our summer season, and to begin laying plans for an equally gainful and auspicious winter. But first, please enjoy this sumptuous feast, brought to us by our benevolent leader, Sam Yuen!” He clapped his hands and waiters appeared, carrying trays of cold-cut pork and fresh pots of tea. The silence dissolved into a contented rumble of voices, punctuated by the clatter of chopsticks and serving spoons. Yut Ho breathed an inward sigh of relief.

As far as banquets went, this one left plenty to be desired. There were only four courses: Cold cuts, soup, beef and noodles. Everything was greasy and over-salted, but even so, Yut Ho ate heartily. There was a magic in this kind of communal meal, and the last time she had experienced it had been back in the village when one of the local boys got married. That felt like a lifetime ago, and she savored the sense of festivity and abundance, even though the food was not nearly as good as the simple fare she ate every day with Lee Yong. Yut Ho smiled at everyone except Sam Yuen, and served Hing Sing from each dish as it came down the table. That won her some appreciative glances from the older men in the hall, and each time Hing Sing served her there was an audible rumble of approval. I can’t believe it, she thought to herself. This is going to work.

Hing Sing was in fine form that night. He didn’t eat much, but his capacity for alcohol was preternatural. By the third course he was making the rounds, drinking a toast at each table and then circling back to do it again. He seemed to know everyone by name, inquiring after their health, families and fortunes in a loud, confident voice. Yut Ho had never seen him like this. “people like Hing Sing,” Lee Yong had said; Now she knew why. He was a jolly, affable rogue and she could almost see herself liking him too.

“But surely, Dr. Tong,” Hing Sing was saying, “Surely you’ll join us in a toast to our prosperity in the season to come! What harm could there be in that?”

“I’ll tell you what harm there is,” replied the trim, middle aged man to whom he was speaking. “It’s the harm that comes from placing profit and petty rivalries above the health of our community!”

Hing Sing hesitated, his glass still raised. He glanced at Sam Yuen. “Dr. Tong, I’m… not sure what you’re talking about but perhaps we should–“

“I’m talking,” said Dr. Tong, in a voice that was clearly audible to everyone in the room, “About the company’s investment in Opium.”

Sam Yuen stood up.

Immediately, the room fell silent. Hing Sing looked at his boss, then at Dr. Tong. Then he looked at Yut Ho, with a pleading expression. As if there was anything she could do.

“Dr. Tong,” said Sam Yuen.

His voice was like two pieces of metal, grinding against each other. It was the voice of a demon or a dragon out of a shadow-play. The voice of a killer.

Dr. Tong stood. He was older than Yut Ho had thought, certainly much older than Sam Yuen. His face was calm, but he was sweating and his forehead glistened beneath his receding hairline.

“Sam Yuen,” he replied in a steady voice. He must be brave, thought Yut Ho.

“As an herbalist and a healer, I must object to the company’s decision to take part in the sale of opium among the people of Chinatown,” said Dr. Tong. “The poppy is a powerful plant, and it has its uses. However, I know all too well the terrible toll it can take when it is sold for profit, and used too freely. We all do.” He looked around at his companions for support, but nobody would meet his gaze.

Sam Yuen did not move, but his shadow on the wall behind him seemed to grow larger and darker as he tilted back his hat to reveal a face so hard and spare that it could have been cast in bronze. His eyes caught the light of the red lanterns and seemed to glow in their deep, dark sockets. Like a cat, thought Yut Ho. Or a wolf.

“You,” he said to Dr. Tong, “Are a fool.”

“That may be true,” Dr. Tong retorted, “But–“

“It is true.” Sam Yuen stalked around the table, and stood on the edge of the dais. There was something in the way he moved which Yut Ho found unnerving. A kind of fluidity that made it impossible to know what he was thinking, or what he might do next.

“Your moralizing is nothing but the squeal of a soft-hearted weakling, who would rather salve the festering wounds of filthy Gwailo than defend his community against the greatest threat it has ever seen: Yo Hing!”

He roared out his rival’s name in a challenge that rattled the spoons in their empty trenchers and made Hing Sing cringe. Dr. Tong shook his head.

“No. Yo Hing is a rascal and a vagabond, but the greatest threat to our community is the division that we have created within it. We have only ourselves to blame. These past few years, the Sze Yup company has stopped serving the community like a benevolent association, and started serving itself like a fighting Tong! I cannot stand here and watch our company sink so low so low that all we do is struggle against Yo Hing for supremacy in the vice trade.”

“Then go.” Sam Yuen pointed to the door. Yut Ho didn’t even see him move. One moment his arm was by his side, and the next moment it was extended. Perhaps it was a trick of the light.

Without another word, Dr. Tong. turned, and walked out.

Sam Yuen lowered his arm, and looked around the room.

“Anyone else?” He asked flatly.

It had been a night of many silences, but this one was the deepest of them all.

“Good.” Said Sam Yuen. Then he turned and walked slowly toward the door. Hing Sing signaled to Yut Ho, and the two of them hurried after Sam Yuen. The company members watched them go, with relief written plainly on their faces.

“I’m really very tired,” said Yut Ho. “I think I need to go to bed.”

They were sitting around the dining table in her apartment. There were five of them: Herself, Hing Sing, Phoneix, Jade, and Sam Yuen. Everyone except Yut Ho had been drinking Baiju and playing some sort of Gawilo card game ever since they arrived from the banquet, oven an hour ago.

Nobody answered her, so Yut Ho got up to leave. She was halfway across the room when Sam Yuen said “Stop.”

She froze. Icy tendrils of fear caught at her throat and wriggled down her spine. Please, she thought. Her room was so close. Please.

“I just want to know one thing,” Sam Yuen Said. Yut Ho turned and faced him, with her arms stiff by her sides. How much Baiju had he drunk? It was impossible to tell. His voice was harsh and clear. “How is it that you can sit here, without saying a word, while your husband giggles and gossips and carries on with his two favorite whores?”

Hing Sing, Jade and Phoenix had indeed been carrying on some whispered conversation until Sam Yuen spoke. Now they were looking back and forth between him and Yut Ho with a mixture of curiosity and apprehension.

Yut Ho spoke carefully. “I don’t have any problem with Hing Sing talking to his associates.”

Sam Yuen laughed. “Talking? Do you think that’s all they do?”

“It’s not,” said Phoenix, catching on. “We do all kinds of other things downstairs, when you’re not around.”

Yut Ho gritted her teeth. “That’s none of my business,” She said.

“Why?” asked Sam Yuen. “Don’t you have any self-respect?”

Yut Ho was silent.

“Ah. I see.” Sam Yuen sounded disappointed. “She has none. Perhaps it’s for the best. After all, what kind of self-respecting woman would marry Hing Sing? She must have been desperate. Don’t you think so, Jade?”

Jade nodded. “Must have been. I’ve got plenty of girls downstairs who’d rather work a few years on their back and save up some money of their own than marry a man who keeps them cooped up in the attic and never gives them a good–“

“Language!” interrupted Phoenix. “Don’t you know she’s a sweet little country bumpkin who couldn’t tell the difference between a man and a bitter melon? She doesn’t even know what we’re talking about. That’s why Hing Sing never complains about her being such a frigid little bitch: He knows that she’d be about as much fun as a dead–“

“Shut up, Phoenix,” Yut Ho snarled. “If I wanted any of that from Hing Sing, I’d take it. Seeing as I don’t, though, and seeing as he’s too besotted with liquor and opium to be much of a man to anyone, I’d rather have him waste his efforts on you.”

Sam Yuen made a noise that might have been a laugh, but sounded more like a hiss. “Did you hear that, Hing Sing?” He asked quietly.

Hing Sing was shaking his head and mumbling something. Sam Yuen talked over him.

“She said you’re too much of a drunk to be a man. Is that true? Prove it’s not true, Hing Sing. Get up and hit her. Then we’ll see how much of a man you really are.”

Hing Sing shook his head more vigorously, but Phoenix grabbed him and dragged him to his feet. “That’s right, Hing Sing,” she cackled. “Hit her! show us how much of a man you are!”

“No,” Hing Sing’s voice was plaintive. “No hitting, I’m…” He teetered on the spot, and Phoenix grabbed him again. “I’m sure we can find a mutually beneficial arrangement.”

“If you’re not man enough to hit her,” said Sam Yuen “then I’ll have to do it for you.”

“No!” squawked Hing Sing. He broke away from Phoenix and stumbled toward Yut Ho, but it was too late. In a flash, Sam Yuen leapt over the table and across the room. Yut Ho didn’t have time to react. Just as she was raising her hands to cover her face, a terrible force slammed into her chest. She felt a strange sensation of weightlessness, and then her head collided with the wall, and she crumpled to the floor. She tried to get up, but her lungs didn’t seem to be working. Her mouth was full of a salty, metallic taste.

She looked up just in time to see Hing Sing hit the ground. His face was turned toward her, livid from the blow that had knocked him unconscious. Phoenix was still cackling, but a glance from Sam Yuen, and she fell silent. He walked over to the table, where his hat was sitting next to some cards and an empty Baiju bottle.

“Better clean up this mess,” he said quietly. Then he put on his hat, and went downstairs. The sound of his heavy boots receded slowly into the dark.

The next morning when Lee Yong arrived, he found Yut Ho waiting for him in the kitchen. She was wearing a blood-red cheongsam with black embroidery, which clung to her body like a flame clings to a burning brand.

She handed him a cup of tea, which smelled like wildflowers, and moist earth. Then, without waiting for him to finish, she took him by the hand, led him to her room, and shut the door behind them.

This was going to be a very unusual day.

Emma:If you enjoyed the show and want to hear more, tell us in a review, and become one of our community backers at www.bloodongoldmountain.com/support. Remember to follow us wherever you listen to podcasts, and reach out with thoughts and questions on Instagram and Facebook at Blood On Gold Mountain. Episode 7, “The Underworld,” will be released on Wednesday June 16th.

Blood on Gold Mountain is brought to you by The Holmes Performing Arts Fund of The Claremont Colleges, The Pacific Basin Institute of Pomona College, The Public Events Office at Scripps College, The Scripps College Music Department, The Entrepreneurial Musicianship Department at The New England Conservatory, and our Patreon patrons.

It is written and produced by Micah Huang, narrated by Hao Huang, and hosted by Emma Gies, featuring original music by Micah Huang and The Flower Pistils. A special thanks to Hao Huang for piano wizardry, Kusuma Tri Saputro for the amazing artwork, Sheila Kolesaire for her critical PR guidance, Muqi Li for her brilliant guzheng playing, Rachel Huang for her editing prowess, and Evo Terra from Simpler Media Productions for his immense expertise and support.