Shownotes

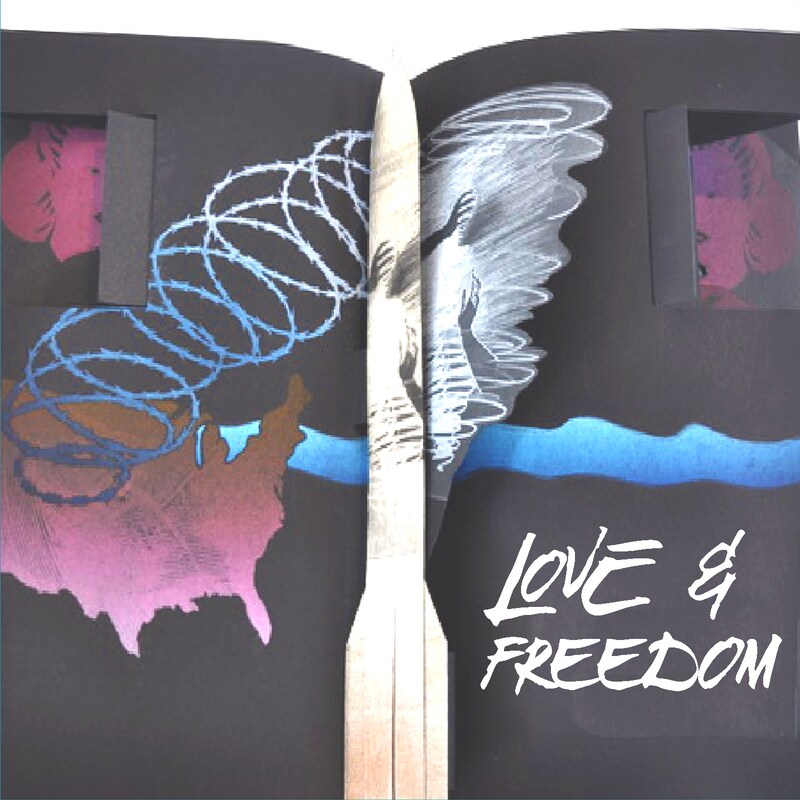

Episode 4: Beth Thielen - Love and Freedom

Bookmakers at San Quentin. Not surprising, given "Q's" clientele. But no, we're talking about real books with real pages that are awe-inspiring works of art.

Transcript

Needless to say, this year has been both odd and extraordinary. Odd? --- Well, Pick your poison. Extraordinary? --- Because we spent the year having amazing conversations with dozens of creative change agents who are kicking ass making a real difference in the upside-down world we live in. These conversations have helped us at the Center for the Study of Art & Community manage the lurking shadows and have sparked some new ideas and even optimism.

We're excited to be starting our second season on February 2, but in the meantime we thought it might be nice to revisit some of our most popular past episodes.

First up is Beth Thielen, a book maker who works across the by here from us at San Quentin. Actually she's not taking bets, but she and her students at "Q" are making a lot of awesome books. Have a listen.

Bill Cleveland: At the time, what came to be known as the classic or a version 1.0 was considered a modern marvel. After a short wait for what was called booting up, and a few clicks, the text seemed to appear magically on a ten by twelve screens set into a plastic computer case. Eventually, the white on black text gave way to a gloriously glowing black on white. Moving through the text was accomplished using a small, palm-sized oblong disk that was endearingly called a mouse. Unfortunately, the computer was quite heavy and wired, so reading was typically a one person, one stationary screen affair.

Then, the "two point oh" model with names like Kindle and Nook changed everything. It still had a screen and needed juice, but the wires were gone, and it was small and thin and light enough to take anywhere without a hassle. Going through text with the push of a button or flick of a finger on the screen made reading almost fun. There were a few downsides, though. After you paid for the machine, you still had to fork over for whatever it was you wanted to read. The thing also needed charging, and eventually, they would quit working from being dropped or just wearing out, which meant you lost whatever you were reading, which wasn't that big a deal because you actually never really owned it.

But today, with the advent of the extraordinary Codex 3.0, also known as, "a book," all that came before seems quaint. This new text delivery system has so taken the world by storm, seven in ten humans now consider reading their number one favorite personal activity. While retaining the handiness and readability of its predecessors, this new model is both less expensive and far more versatile. This is due, in part, to the fact that after you purchase it, you actually own it, which means these books can be gifted or shared or even sold. There is speculation that eventually books will be collected in repositories that some are already calling libraries and could actually increase in value over time.

But the most delightful features of these clever little packages of text are embodied in their design. Now, depending on their size, which is varied, they can fit neatly in your hands or lap for easy reading. They're ingenious cover, and page feature allows you to open, feel, and manipulate the enclosed paper sheets in sequence from front to back, the reverse, or even randomly. This is called browsing. If you want to remember where you left off, you can use what is called a bookmark or even bend the corner of those little pages. It's your choice. Another improvement is its sturdiness. You can drop it, sit on it, even step on it. And it will still function like it was new. And best of all, there are no batteries, no wires, and no moving parts. Finally, each book comes with a multigenerational lifetime guarantee that stipulates that with reasonable care and handling, each book will be fully functional for hundreds, if not thousands of years.

Bill Cleveland: Excerpted from the "Modern Marvels of the Post Pandemian Epoch" by William T. William, 2047 A.D., also referred to as 26 P. P. E.

Bill Cleveland: From the Center for the Study of Art and Community, this is Change the Story Change the World. I'm Bill Cleveland.

Bill Cleveland: Long before the advent of Books, Inc., Amazon, and the Kindle, the making of books was considered a vital and essential art form. Over many millennia, the connections forged between humans and their books were seen as both fundamental to human progress, and as sacred and dynamic relationships. Given this, if I were to add yet one more evolved stage to the oddly imagined Future Books saga I just shared, it would be embodied in both this venerable history and in artists like Beth Thielen. Beth is a contemporary book artist who stands with one foot in the monasteries and studios of her revered bookmaking predecessors and another in the altered universe that is only now being shaped in the spectral shadow of our global pandemic.

Beth describes her life pursuit as asking questions and making connections. Her work combines the narrative and tactile and sculptural with a passion for the transforming affirmation intrinsic to the act of creation. This passion has fueled the making of hundreds of extraordinarily beautiful, inspiring, and provocative works of art. These books of every imaginable shape, size, and material have been crafted by Beth and hundreds of bookmakers, who she has mentored over her long career. This community of artists and their stories have been nurtured and fed and celebrated in prisons, group homes, hospitals, senior centers, and schools all across America.

I first met Beth in one of those other places during my time running the California Arts in Corrections program. She said she wasn't sure what to expect, but after her first visit to the California Institution for Women in 1985, she knew she had come to the right place. She's been showing up at those right places ever since.

Part One: Love and Freedom

Bill Cleveland So let me begin by saying, first of all, thank you. Thank you for agreeing to do this. I'm looking forward to learning more about your path and your journey. Let's begin by saying if someone were to ask you, "what is it you do, Beth," what was your answer to that question? What is your work in the world?

Beth Thielen: I would say that I am an artist who works with incarcerated and troubled communities, and that's where my work comes from. That's the kind of work that comes out of me. It's the kind of questions that form in my work, such as the question I shared with you the other day that I had when I first started with Arts and corrections in California was one day I was at my drawing table after teaching a week in California Institution for Women, and a question formed in my head, which was what relationship does love have to freedom? And I had just seen a mug shot of a woman in prison from back when San Quentin was a private prison at the turn of the century, and she was in for bigamy. It said that her age was 27, but she looked easily 57. She looked so hurt, and haggard and that form the question, what happened here? What's the relationship between love and freedom? Because boy, something happened here.

Bill Cleveland: So you have a practice that is social in nature, in that you go into institutions and you engage with a wide variety of people, some of whom have some experience making things, others who don't. You also have a studio practice that you talk about the relationship between the two.

Beth Thielen: Yeah, well, you know, landscape painters need to be in a landscape. I'm of an interior landscape. I'm looking at the story of our country in a way through my own vision of the landscape. I had a drawing teacher when I was very young at the Young Artist Studios in the Chicago Art Institute, and she would have you go into a room to draw where the mom was. But you were there only to look, and then she would make you go into another room to actually do the drawing, so you would have to capture it in your head and then move into the other room to do the drawing. So, in a way, I do that I walk into prisons, and of course, you're not allowed to bring a camera, but I know how to catch it in my head.

Bill Cleveland: So, one of the things that happens when you enter into institutions and you engage the people who live and work there, is that you inevitably come into contact with the stories they represent. Could you talk about the relationship between the story field you encounter in these extraordinarily complex places and what happens when you make work?

Beth Thielen: Well, I'm often moved by what my students say to me. I did a Pop-Up book where each page was a sentence spoken in prison to me, and I just would write down the sentence and then have there's pop-up book image of that particular sentence, and one of them was simply this place change issue was what a woman said to me. It was such a loaded sentence. Her sentence, you know, that it conveyed and made the power of the image happen. So, when I'm there as a visual artist, I'm using seeing and all the ways that one sees pulling what's happening before me and to a translatable image that I can then share in a piece of artwork.

Bill Cleveland: Do you think of yourself as a witness?

Beth Thielen: Yes., and as a kind of a distiller because I'm not just there to witness, but to make connections.

Bill Cleveland: How does the act of teaching make connections?

Beth Thielen: Well, it's very hard to just go in and draw somebody's portrait if what you're drawing is what I'm doing, which is telling a whole story. So the teaching is a way for me to be there and share and learn from my participants in the process of making together without it having to be "Tell me your life story. I'm going to do a book, or I'm gonna do a painting". And, you know, it takes a lot of time, so right now, I'm working with girls at a group home there. They're locked down. I can't see them right now. But this is volunteer work on my part. I go twice a week, and I just do whatever we want to do, whatever they are up to doing, but they informed me about the dilemma of a group home by my just being present and watching what's happening and how so much of the seeds of what has happened in corrections happens so young with these girls. So that's the process.

Bill Cleveland: So, in essence, you're there bringing a practice.

Beth Thielen: I'm bringing a practice, Yes.

BC: And what do you think is happening for them?

Beth Thielen: I don't always know. I know that the men at San Quentin when I get there, they're waiting in line to get in. They don't stop. They don't take a break. I don't even sometimes pee until four o'clock when they're called out because they are showing me their portfolios. They're asking me questions. We're doing or making an artist book, or we're making individual sketchbooks for them or where printing. But there's all this other stuff going on to where they're really honed into my presence in a way that doesn't happen anywhere else in the world, and I'm just meeting at as best I can. There's that hunger that is so fantastic.

Bill Cleveland: So Beth, somewhere along the line, you took a sharp and very focused turn into this practice of yours being an artist and engaging the world, and what I would describe as a healing practice. How did you come to that?

Beth Thielen: I come from a very large, dysfunctional German Catholic family. When Susan Hill at ArtsReach at UCLA started doing classes in the prison system in California, she asked if I wanted to try it. I went in, and it was a California institution for women. I got in there, and within the first hour, I said, jeez, this feels just like home. I can do that somewhere weird. You know, t's the problems that we face there. You have to work them out individually, even if they are something that looks like you're doing out in the world. You're trying to find a solution to something innate, so I suppose with my upbringing, I was already asking the questions that would make me good for that environment.

Bill Cleveland: So before you got on the train, so to speak, to California Institution for Women, was art a big part of your family life? What took you down the path of studying art in the first place?

Beth Thielen: I was very lucky. I can remember in kindergarten being introduced to fingerpainting and having all these big jars of tempera paint and sloshing it around a big piece of paper, and suddenly I saw and what I was doing, this dense forest where me and my twin brother were trying to get through this tangle of logs. It was just an aha moment. It was like, oh, that's what's going on…And, you know, I was very lucky that at a very early moment, the teacher had to shut me up. I was like talking to her about the painting; you know that I did. And all that's going on and that I could see it so clearly. But an artist was born. I was hooked.

Bill Cleveland: And your family supported this?

Beth Thielen: No, not so much. No. I remember when my father was, you know, he got his education through the military. My parents had eight children, and when I said, gee, I think I'm an artist, I want to go to the Art Institute of Chicago. My father just yells at me, and he said, Excuse me, who the ____do you think you are? And I said, Gee, Dad, I think I'm an artist. Cause he in our family, if you wanted college, you had to do military. That was just how it was. So, I broke the rules and went off on my own to art school without support, but I did it.

Bill Cleveland: So, is there a part of your early biography that travels with you when you walk into these places, maybe with these young women that you're working with?

Beth Thielen: Oh, absolutely. I see my early childhood in these girls. My childhood had some abusive parts to it. And I think in the American psyche, if you want to look at damage, look at young girls, in particular, there's something that happens where a young boy can devil may care. There are all these different words that say it's OK to make mistakes, whereas girls, you're breaking up the family. It's like on visiting day for holidays at the prison. The line is around the block for men's prisons. And there's very few for women's prisons that come in. There's a shame in the feminine mystique that's so deep. So, looking from the California prison system to working with girls in group homes, I can really catch how they are fodder for all that ails you.

Bill Cleveland: You described yourself as sort of breaking the rules of your family, and when you were just talking, I had this image of how much harder it is for some women to be a rule-breaker where for men in some cases, that's seen as romantic and adventurous and experimental…And for women, because you are in some cases, the rock.

Beth Thielen: Right, right…Disturbing the peace of the status quo. Get in the kitchen—all that.

Bill Cleveland: So, you talk about California institution for women. That was a long time ago that you first went into the institution.

Beth Thielen: I think I started nineteen eighty-five.

Bill Cleveland: So you've been doing this ever since? ….mhmm…And you're no longer in California. You're on the East Coast now. So obviously there's something about this that has moved from an opportunity to a significant part of your practice. How is that? How did that come about?

Beth Thielen: It goes back to that first question. What relationship does love have to freedom? It's the heart of our failure as a country, really. And so, to me, if I have some mature person now can say I'm trying to tell the story of my country through this experience, then I have to deal with are incarcerated. I have to deal with the fact that we have the largest percentage of people in prison in the world because it's the heart of what our trouble is, how we have not become who we should be as a nation. It's at the very heart. So, yes, that's why I'm there.

Part two, Wisdom meets beauty

Bill Cleveland: At the end of part one, Beth returned to her initial question, what does love have to do with beauty? She also touched on how dealing with both the ugliness and the beauty she finds in her present experience helped her address another of her burning questions. What is the story of my country, and how can I help change it for the better? In part two, we delve a little deeper into these questions. So, Beth, the irony, of course, is that for most folks, the carceral state, these two and a quarter million souls hardly exist in their consciousness. These institutions are out of sight, out of mind. And I would maybe point out that right now, these places are particularly dangerous with regard to the pandemic. So, given this urgency as a context, could you talk about what you've been doing recently that personifies the intention and hope for impact of your work?

Beth Thielen: Well, I was just in San Quentin in March, two days before they locked everything down. And I'm working on a limited-edition artist book of about 30 copies where each of the guys will get to keep their own copy. We're all making one together as a group, and I shared with them my artist's statement about them, and how I view them and what I was telling you about how they're there waiting for me at 8:00 a.m. and they're showing their portfolios, they're sharing their paintings that we work until they're called out for count at 4:00. No one takes a break.

Art matters here. I don't get that at the university, but these people that I meet in my classes, they often have sons in prison or grandparents in prison. They have a whole generational span of experiences in prisons, and they meet it with a courage and a generosity and a strength. I'm in debt to their courage, and I feel a responsibility to get people to understand that it's these people who are living in this horrible situation and have for such a long time, that are adapting to where we need to go faster than the rest of us. They are like a species living at the edge of sustainability, where there's adaptation occurring, where there's mutations occurring that allow them to adapt and change, and these people bring so much imagination to lack. For me, that's our way that we have to go. If we're going to solve our problems with the environment, we're going to solve our problems with prisons. If we're going to solve our problems with how we do our communities post-pandemic. So, for me, the hardships they have endured give us a way to our future if we can accept and not be afraid of the hard knowledge, save one.

Bill Cleveland: So do me a favor. I would...

Transcripts

Bill Cleveland: At the time, what came to be known as the classic or a version 1.0 was considered a modern marvel. After a short wait for what was called booting up, and a few clicks, the text seemed to appear magically on a ten by twelve screens set into a plastic computer case. Eventually, the white on black text gave way to a gloriously glowing black on white. Moving through the text was accomplished using a small, palm-sized oblong disk that was endearingly called a mouse. Unfortunately, the computer was quite heavy and wired, so reading was typically a one person, one stationary screen affair.

Then, the "two point oh" model with names like Kindle and Nook changed everything. It still had a screen and needed juice, but the wires were gone, and it was small and thin and light enough to take anywhere without a hassle. Going through text with the push of a button or flick of a finger on the screen made reading almost fun. There were a few downsides, though. After you paid for the machine, you still had to fork over for whatever it was you wanted to read. The thing also needed charging, and eventually, they would quit working from being dropped or just wearing out, which meant you lost whatever you were reading, which wasn't that big a deal because you actually never really owned it.

But today, with the advent of the extraordinary Codex 3.0, also known as, "a book," all that came before seems quaint. This new text delivery system has so taken the world by storm, seven in ten humans now consider reading their number one favorite personal activity. While retaining the handiness and readability of its predecessors, this new model is both less expensive and far more versatile. This is due, in part, to the fact that after you purchase it, you actually own it, which means these books can be gifted or shared or even sold. There is speculation that eventually books will be collected in repositories that some are already calling libraries and could actually increase in value over time.

But the most delightful features of these clever little packages of text are embodied in their design. Now, depending on their size, which is varied, they can fit neatly in your hands or lap for easy reading. They're ingenious cover, and page feature allows you to open, feel, and manipulate the enclosed paper sheets in sequence from front to back, the reverse, or even randomly. This is called browsing. If you want to remember where you left off, you can use what is called a bookmark or even bend the corner of those little pages. It's your choice. Another improvement is its sturdiness. You can drop it, sit on it, even step on it. And it will still function like it was new. And best of all, there are no batteries, no wires, and no moving parts. Finally, each book comes with a multigenerational lifetime guarantee that stipulates that with reasonable care and handling, each book will be fully functional for hundreds, if not thousands of years.

Epoch" by William T. William,:Bill Cleveland: From the Center for the Study of Art and Community, this is Change the Story Change the World. I'm Bill Cleveland.

Bill Cleveland: Long before the advent of Books, Inc., Amazon, and the Kindle, the making of books was considered a vital and essential art form. Over many millennia, the connections forged between humans and their books were seen as both fundamental to human progress, and as sacred and dynamic relationships. Given this, if I were to add yet one more evolved stage to the oddly imagined Future Books saga I just shared, it would be embodied in both this venerable history and in artists like Beth Thielen. Beth is a contemporary book artist who stands with one foot in the monasteries and studios of her revered bookmaking predecessors and another in the altered universe that is only now being shaped in the spectral shadow of our global pandemic.

Beth describes her life pursuit as asking questions and making connections. Her work combines the narrative and tactile and sculptural with a passion for the transforming affirmation intrinsic to the act of creation. This passion has fueled the making of hundreds of extraordinarily beautiful, inspiring, and provocative works of art. These books of every imaginable shape, size, and material have been crafted by Beth and hundreds of bookmakers, who she has mentored over her long career. This community of artists and their stories have been nurtured and fed and celebrated in prisons, group homes, hospitals, senior centers, and schools all across America.

rnia Institution for Women in:Part One: Love and Freedom

Bill Cleveland So let me begin by saying, first of all, thank you. Thank you for agreeing to do this. I'm looking forward to learning more about your path and your journey. Let's begin by saying if someone were to ask you, "what is it you do, Beth," what was your answer to that question? What is your work in the world?

Beth Thielen: I would say that I am an artist who works with incarcerated and troubled communities, and that's where my work comes from. That's the kind of work that comes out of me. It's the kind of questions that form in my work, such as the question I shared with you the other day that I had when I first started with Arts and corrections in California was one day I was at my drawing table after teaching a week in California Institution for Women, and a question formed in my head, which was what relationship does love have to freedom? And I had just seen a mug shot of a woman in prison from back when San Quentin was a private prison at the turn of the century, and she was in for bigamy. It said that her age was 27, but she looked easily 57. She looked so hurt, and haggard and that form the question, what happened here? What's the relationship between love and freedom? Because boy, something happened here.

Bill Cleveland: So you have a practice that is social in nature, in that you go into institutions and you engage with a wide variety of people, some of whom have some experience making things, others who don't. You also have a studio practice that you talk about the relationship between the two.

Beth Thielen: Yeah, well, you know, landscape painters need to be in a landscape. I'm of an interior landscape. I'm looking at the story of our country in a way through my own vision of the landscape. I had a drawing teacher when I was very young at the Young Artist Studios in the Chicago Art Institute, and she would have you go into a room to draw where the mom was. But you were there only to look, and then she would make you go into another room to actually do the drawing, so you would have to capture it in your head and then move into the other room to do the drawing. So, in a way, I do that I walk into prisons, and of course, you're not allowed to bring a camera, but I know how to catch it in my head.

Bill Cleveland: So, one of the things that happens when you enter into institutions and you engage the people who live and work there, is that you inevitably come into contact with the stories they represent. Could you talk about the relationship between the story field you encounter in these extraordinarily complex places and what happens when you make work?

Beth Thielen: Well, I'm often moved by what my students say to me. I did a Pop-Up book where each page was a sentence spoken in prison to me, and I just would write down the sentence and then have there's pop-up book image of that particular sentence, and one of them was simply this place change issue was what a woman said to me. It was such a loaded sentence. Her sentence, you know, that it conveyed and made the power of the image happen. So, when I'm there as a visual artist, I'm using seeing and all the ways that one sees pulling what's happening before me and to a translatable image that I can then share in a piece of artwork.

Bill Cleveland: Do you think of yourself as a witness?

Beth Thielen: Yes., and as a kind of a distiller because I'm not just there to witness, but to make connections.

Bill Cleveland: How does the act of teaching make connections?

Beth Thielen: Well, it's very hard to just go in and draw somebody's portrait if what you're drawing is what I'm doing, which is telling a whole story. So the teaching is a way for me to be there and share and learn from my participants in the process of making together without it having to be "Tell me your life story. I'm going to do a book, or I'm gonna do a painting". And, you know, it takes a lot of time, so right now, I'm working with girls at a group home there. They're locked down. I can't see them right now. But this is volunteer work on my part. I go twice a week, and I just do whatever we want to do, whatever they are up to doing, but they informed me about the dilemma of a group home by my just being present and watching what's happening and how so much of the seeds of what has happened in corrections happens so young with these girls. So that's the process.

Bill Cleveland: So, in essence, you're there bringing a practice.

Beth Thielen: I'm bringing a practice, Yes.

BC: And what do you think is happening for them?

Beth Thielen: I don't always know. I know that the men at San Quentin when I get there, they're waiting in line to get in. They don't stop. They don't take a break. I don't even sometimes pee until four o'clock when they're called out because they are showing me their portfolios. They're asking me questions. We're doing or making an artist book, or we're making individual sketchbooks for them or where printing. But there's all this other stuff going on to where they're really honed into my presence in a way that doesn't happen anywhere else in the world, and I'm just meeting at as best I can. There's that hunger that is so fantastic.

Bill Cleveland: So Beth, somewhere along the line, you took a sharp and very focused turn into this practice of yours being an artist and engaging the world, and what I would describe as a healing practice. How did you come to that?

Beth Thielen: I come from a very large, dysfunctional German Catholic family. When Susan Hill at ArtsReach at UCLA started doing classes in the prison system in California, she asked if I wanted to try it. I went in, and it was a California institution for women. I got in there, and within the first hour, I said, jeez, this feels just like home. I can do that somewhere weird. You know, t's the problems that we face there. You have to work them out individually, even if they are something that looks like you're doing out in the world. You're trying to find a solution to something innate, so I suppose with my upbringing, I was already asking the questions that would make me good for that environment.

Bill Cleveland: So before you got on the train, so to speak, to California Institution for Women, was art a big part of your family life? What took you down the path of studying art in the first place?

Beth Thielen: I was very lucky. I can remember in kindergarten being introduced to fingerpainting and having all these big jars of tempera paint and sloshing it around a big piece of paper, and suddenly I saw and what I was doing, this dense forest where me and my twin brother were trying to get through this tangle of logs. It was just an aha moment. It was like, oh, that's what's going on…And, you know, I was very lucky that at a very early moment, the teacher had to shut me up. I was like talking to her about the painting; you know that I did. And all that's going on and that I could see it so clearly. But an artist was born. I was hooked.

Bill Cleveland: And your family supported this?

Beth Thielen: No, not so much. No. I remember when my father was, you know, he got his education through the military. My parents had eight children, and when I said, gee, I think I'm an artist, I want to go to the Art Institute of Chicago. My father just yells at me, and he said, Excuse me, who the ____do you think you are? And I said, Gee, Dad, I think I'm an artist. Cause he in our family, if you wanted college, you had to do military. That was just how it was. So, I broke the rules and went off on my own to art school without support, but I did it.

Bill Cleveland: So, is there a part of your early biography that travels with you when you walk into these places, maybe with these young women that you're working with?

Beth Thielen: Oh, absolutely. I see my early childhood in these girls. My childhood had some abusive parts to it. And I think in the American psyche, if you want to look at damage, look at young girls, in particular, there's something that happens where a young boy can devil may care. There are all these different words that say it's OK to make mistakes, whereas girls, you're breaking up the family. It's like on visiting day for holidays at the prison. The line is around the block for men's prisons. And there's very few for women's prisons that come in. There's a shame in the feminine mystique that's so deep. So, looking from the California prison system to working with girls in group homes, I can really catch how they are fodder for all that ails you.

Bill Cleveland: You described yourself as sort of breaking the rules of your family, and when you were just talking, I had this image of how much harder it is for some women to be a rule-breaker where for men in some cases, that's seen as romantic and adventurous and experimental…And for women, because you are in some cases, the rock.

Beth Thielen: Right, right…Disturbing the peace of the status quo. Get in the kitchen—all that.

Bill Cleveland: So, you talk about California institution for women. That was a long time ago that you first went into the institution.

Beth Thielen: I think I started nineteen eighty-five.

Bill Cleveland: So you've been doing this ever since? ….mhmm…And you're no longer in California. You're on the East Coast now. So obviously there's something about this that has moved from an opportunity to a significant part of your practice. How is that? How did that come about?

Beth Thielen: It goes back to that first question. What relationship does love have to freedom? It's the heart of our failure as a country, really. And so, to me, if I have some mature person now can say I'm trying to tell the story of my country through this experience, then I have to deal with are incarcerated. I have to deal with the fact that we have the largest percentage of people in prison in the world because it's the heart of what our trouble is, how we have not become who we should be as a nation. It's at the very heart. So, yes, that's why I'm there.

Part two, Wisdom meets beauty

Bill Cleveland: At the end of part one, Beth returned to her initial question, what does love have to do with beauty? She also touched on how dealing with both the ugliness and the beauty she finds in her present experience helped her address another of her burning questions. What is the story of my country, and how can I help change it for the better? In part two, we delve a little deeper into these questions. So, Beth, the irony, of course, is that for most folks, the carceral state, these two and a quarter million souls hardly exist in their consciousness. These institutions are out of sight, out of mind. And I would maybe point out that right now, these places are particularly dangerous with regard to the pandemic. So, given this urgency as a context, could you talk about what you've been doing recently that personifies the intention and hope for impact of your work?

Beth Thielen: Well, I was just in San Quentin in March, two days before they locked everything down. And I'm working on a limited-edition artist book of about 30 copies where each of the guys will get to keep their own copy. We're all making one together as a group, and I shared with them my artist's statement about them, and how I view them and what I was telling you about how they're there waiting for me at 8:00 a.m. and they're showing their portfolios, they're sharing their paintings that we work until they're called out for count at 4:00. No one takes a break.

Art matters here. I don't get that at the university, but these people that I meet in my classes, they often have sons in prison or grandparents in prison. They have a whole generational span of experiences in prisons, and they meet it with a courage and a generosity and a strength. I'm in debt to their courage, and I feel a responsibility to get people to understand that it's these people who are living in this horrible situation and have for such a long time, that are adapting to where we need to go faster than the rest of us. They are like a species living at the edge of sustainability, where there's adaptation occurring, where there's mutations occurring that allow them to adapt and change, and these people bring so much imagination to lack. For me, that's our way that we have to go. If we're going to solve our problems with the environment, we're going to solve our problems with prisons. If we're going to solve our problems with how we do our communities post-pandemic. So, for me, the hardships they have endured give us a way to our future if we can accept and not be afraid of the hard knowledge, save one.

Bill Cleveland: So do me a favor. I would like you to take me and the people listening into the prison.

Beth Thielen: OK, well, the recent trip to San Quentin is kind of a strange thing because it's in one of the most beautiful locations in the world. It's right off the... is it the Richmond Bridge there? You come off that bridge, and there you are with the Pacific Ocean on one edge. As you walk into the prison grounds, you show your I.D. and, you know, I bring in Matt knives and scissors and all kinds of things. I have to have them cleared ahead of time; I have to have the marked exactly what I have if I have a Matt knife that has snap-off blades, I've got to make sure they're all counted in the beginning when I right there in front of the officer and they all have to come out when I leave, or I'm not leaving. And you know, I wouldn't want anyone hurt because of something I did, so I'm really, really paying attention to all of that and making sure that no officer is hurt or I'm not hurt, or no inmate is hurt because of what I've done or neglected. Then you have to keep flashing your I.D. as you go through these heavy gates that cling and clang around you and you walk into the prison area and there are times where you have to stop and pull over if there are officers with inmates that they're taking through, that they just don't want you to have, they don't even you want you to look at them particularly, they just want you to really pull over, and you get to your room. An officer has to unlock it for you. The men swarm in. They have all of their little portfolios with them. They have their little bagged lunches, so they don't have to leave, they can stay all day, and they are immediately taking this empty space and setting it up for the art room. Now, that means that they take off full-size etching press that is swept down in the cabinet, and they've figured out this great way on these heavy metal hinges to bring that press up on top of the counter and then have that setup. Then if there's not printmaking, that big old press gets swung back down inside the counter. So there's counter room for something else, and the whole room transforms itself in a few minutes into the space that's needed at that moment. It is a really amazing thing to watch how, you know, space at such a premium institution like a prison. The way in which these men have managed to make this room work for every discipline that can possibly fit in this tiny space is a sight to see. It's really a creative explosion that happens just to see them open the room to whatever we're doing.

So, I am working on this artist's work with them, which requires a lot of printmaking, and I introduce it usually with the piece I was sharing with you where I've adapted a little saying from Tich Nah Han, about how a paper and a cloud are so close. You hold this piece of paper; you can see that there's a cloud floating in this sheet of paper, paper, and cloud. They are so close. You can see the cloud in there because it takes rain to make this piece of paper, so the cloud is in there. That basically comes to everything is in this piece of paper. And then when they come into the art studio, they bring everything with them to work on yourself in the art studios, to work on the world, and that's where we usually start. You know, they cajole, they vie for who sits next to me when they are flirtatious at some points and very respectful. They always make me a nice coffee. They make sure I'm, you know, well situated in the room and I've got what I need. And it's really quite a lovely experience.

Bill Cleveland: And are most of your students in a continuing relationship with art-making, or are there some newcomers?

Beth Thielen Well, it's always changing because, you know, they don't have a lot of control sometimes about where they are or what institution they're in, or you know, what housing unit gets out that day. So, it's always changing. There are always new guys, and there's always guys who I've seen over the years. It's just a great mixed bag, and there seems to be a kind of a system where the guys who've been in there a long time kind of shepherd the younger guys into that practice. It's quite something to see. It's quite a lovely little guild, in a way.

Bill Cleveland: Now, Now, San Quentin has a mission that has changed significantly over the years. When I was with the department, it was what is known as a level four and was also the oldest prison, right? Yes. And it still has condemned row, does it not?

Beth Thielen: Yeah, it does, yeah… You know, there are so many things you take for granted now, well-run art room that you have to pay attention to, but is I'm pretty lucky to be in a space like that that even allows me to bring that knives and scissors and, you know, printing can do things like that.

Bill Cleveland: So you mentioned a book that is the object of this particular workshop. What stories are rising up in the pages of this book?

Beth Thielen: Well, we're basing that on old mug shots from San Quentin. So, each of the men, you know Peter Marks, is the wonderful photographer who does such beautiful portraits of the men. He came in, he shot photographs that we're making into etchings, and the men are printing their own etchings. Each man holds up a chalkboard like they would back in the old days of San Quentin mug shots, and instead of it being the sentence and how long you're in and what you're in for written on a piece of chalkboard, it's a sentence, could be a question or just a statement that the men have. So, Lamavis. wrote in the first one in the book, when you open the book, you see his portrait of Lamavis, and it says, "Art is wisdom that meets divine beauty." Isn't that something?... Whoa… Oh, I know. And some of them say things like, my mistakes don't represent who I am. Some of them say things like, what if I just walked away? So, there's all these different sentences that they have that they're holding up, and we're doing etchings that we'll then unfold out of a large black tower and encircled a tower with their statements.

Bill Cleveland: Wow. So, when you say etchings, could you describe how a drawing becomes an etching?

Beth Thielen: Yeah. Well, it's great because usually with the etching process, you have to use very horrible chemicals to make an etching, and I couldn't get in, get those in. With the new technology, I can make an etching clay by just exposing the plate to light and then processing it in water. I can teach the guys etching because this process is now non-toxic. I don't have to use solvents. I don't have to use nitric acid. I can really just use water. And so that's why this is a great project for them because it allows them to do their portraits in an etching. And if we take the plate after it's been processed, and we get up, and then you're removing the excess ink, and only the ink that's in the best areas will stay, and then they wipe it down, we print it on the etching press, and there's this beautiful portrait of them holding their floorboards.

It's a long process that takes a lot of time. You have to do three or four prints before you get it right, which can be frustrating, but it is it's a good practice. And I'm really happy that now etching is available to them. When we finish this project, we'll do some etchings of their drawings because they're drawings are magnificent. It'll allow them to print editions of their drawings, then, in a new way.

Bill Cleveland: So, describe how the etchings become the pages of a book that is then reproduced in multiples.

Beth Thielen: Well, I come from a tradition of artist's books, which is an artist's way of taking the form of a book and making it a sculptural object where you would make, you know, five books that look like a wave. And that's the whole edition, and it's something that you made up, and it becomes an art object. But it also is something that has a narrative cause I like to do narrative work. So, it's great for me. It's a great way to do visual storytelling. You can make things look like a stage set that unfold and tell a story. And also, one of the reasons I love books with this population and also sharing this population with others is that in a book, it's something intimate. The person, the viewer has to turn the page. They're immediately engaged physically with the object. And it's that kind of one on one kind of to see each other that I want to bring in to the dialogue to bring them the men that I work with into a dialogue that is private and profound for each person turning a page. So the book works really well that way.

Bill Cleveland: So how many books will be made?

Beth Thielen: Thirty, and they're all made with archival materials. I've got Stonehenge paper with black Meraki hinging on a Kozo White paper, and if all the materials of the book itself is a candle petal linen binding cloth. So I'll be giving those two exhibitions, and also they'll be copies going to universities and museums. And the whole purpose of doing it to our archival museum standards is to be like the fairy godmother for Cinderella. Well, I'm giving these guys the proper dress to go to the ball and be represented in the discourse, in museums, and in universities about our incarcerating state and what's going on in the world. So that's the purpose for bringing it to this level with them.

Bill Cleveland: You know, this brings to mind Bill Strickland and the Manchester Craftsmen's Guild in Pittsburgh. Bill believes that deep wounds need the most potent healing. So, when you bring that powerful medicine, the painstaking work, and the best materials, and the slow process of learning you can have, the most profound impact is that you're thinking here.

Beth Thielen: Well, it's also I think the healing is not so much about healing the incarcerated. It's healing those who look at the incarcerated with hatred. So, they are bringing their courage and openness and deep heart to the conversation to heal up.

Bill Cleveland: So will these gentlemen have the opportunity to send these to loved ones or…?

Beth Thielen: Well, first, I have to get back in there to finish them, which is going to be a challenge. I'm doing this with Katja McCulloch, who is the regular teacher at San Quentin and the printmaking program, and we're talking about, well, do we make the museum copies outside of prison? In the meantime, while these guys can't help out with this. But, you know, it's so important to have their involvement. We'll see how it goes. I really want them to have the whole process since they're making.

Bill Cleveland: So, we've referenced this a couple of times during this conversation, but now I like to ask you; specifically, we're in a very unique time in world history. I'm wondering, given your long practice in difficult circumstances with distressed communities and people, what's rising up for you through this period of what I'm calling planet Covid?

Beth Thielen: Yeah, yeah. No. Dr. Jason Clay of the World Wildlife Fund. He said that we won't solve our environmental problems unless we solve our social and economic ones. I think that hopefully, if we can get a new administration into the White House, that we can maybe go back to something like the WPA or the Green New Deal. I think that these guys, with their skills, with the way they bring imagination to lack that we could do prison reform and bring them into the Green New Deal as a partnership of kind of an abolition partnership of bringing this community into solving the problems that we have with community.

They're ready. They've been doing the hard work for so long. They have the skills we need. We need them. And I don't know how we'll get that through to the forces that be, but we're missing a real opportunity if we don't take advantage of how hard these people have worked at redemption and how hard they've worked at bringing imagination to lack the skill we need right now.

Bill Cleveland: So one irony, of course, is, is that these gentlemen have lived in a situation which we're only just encountering ourselves through the structure that has been designed to try and protect us from this pandemic. I'm wondering if maybe some of the things they have to teach us to have to do with how to be in partnership with your fellow humans in ways that are constructive. Yeah. Yes. And have, you know, compassion and learn how to how to trust, again, in an environment that we used to take for granted that has now been altered maybe permanently.

Beth Thielen: I think so.

Bill Cleveland: Beth, I've been looking forward to this conversation for a long time.

Beth Thielen: Well, thank you for thinking of me. I so enjoyed seeing the first podcast that you did and really enjoying how you're studying this up.

Bill Cleveland: What you just said really makes me feel good because you were able to see things in the podcast.

Beth Thielen: Yeah, I did. And, you know, seeing as so much more than the eyes.

Bill Cleveland: Well, Beth, that's for sure. And given that an important part of our conversation has been the amazing artwork that you have helped bring into the world. I'd like to refer our listeners to a Web site where they can actually see it.

So, listeners, if you want to be inspired, please go to www.vampandtramp.com. That's vampandtramp (all spelled out) dot com. Look for Beth Thielen. That's t h i e l e n in the search function. So, thank you again, Beth, for sharing your stories.

And to our listeners. Thank you for tuning in. Please join us for our next episode. Change the story Change the World is a production of the Center for the Study of Art and Community. It's written and directed by Bill Cleveland. Our theme and soundscape are by Judy Munsen. And please, if you've been provoked or inspired, join the continuing conversation and check out our show notes at the center's Web site at WW W.artandcommunity.com. Thanks.