Shownotes

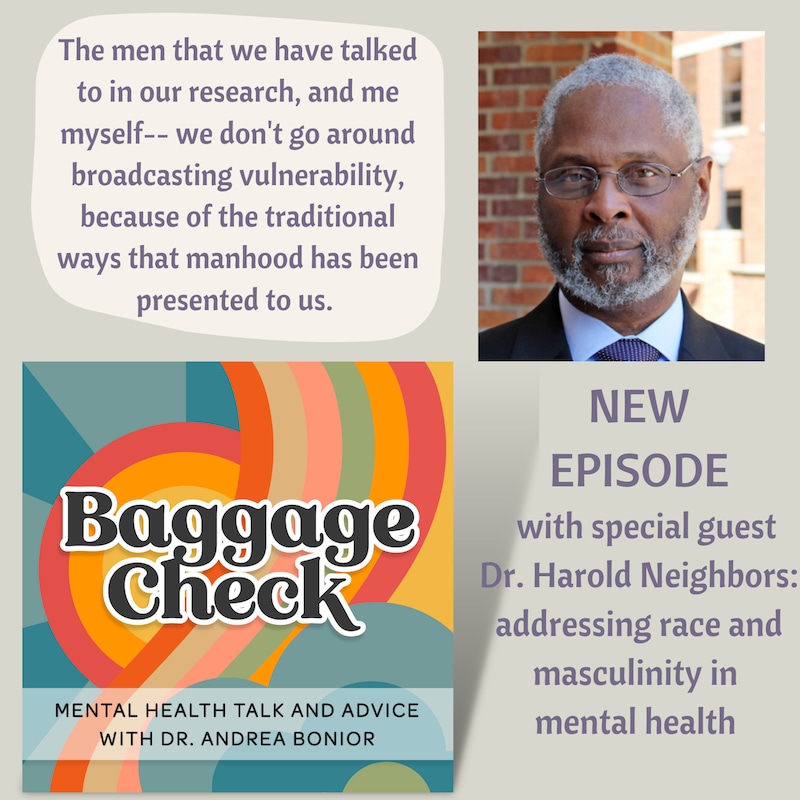

They told him that a program encouraging Black men to gather and talk about their mental health would be a total bust. And guess what? Man Up, Man Down was anything but. In today's episode, we welcome Dr. Neighbors, professor emeritus at University of Michigan and professor of Public Health at Tulane University, for an in-depth look at his Man Up, Man Down program, Tough Guy Syndrome, racism versus "color-blindness" in the therapy room, socioeconomic factors in mental health access, social isolation, gender differences in friendship, and how mental health and health are one and the same. Join us for a conversation that gets real about what a white female psychologist-- and all of us-- can be doing to make positive societal changes.

Follow Baggage Check on Instagram @baggagecheckpodcast and get sneak peeks of upcoming episodes, give your take on guests and show topics, and gawk at the very good boy Buster the Dog!

Here's more on Dr. Andrea Bonior and her book Detox Your Thoughts.

Here's more on this podcast, which somehow you already found (thank you!)

Credits: Beautiful cover art by Danielle Merity, exquisitely lounge-y original music by Jordan Cooper

Got a question for us? Reach out to us on Instagram!

Transcripts

Dr. Harold Neighbors: I mean, a number of my colleagues were kind of skeptical. Basically, oh, you can't get Black men to get together and talk about mental health. You can't do that. And so we were like, yeah, maybe we can't, but we're going to try.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: And thank goodness you did.

Dr. Harold Neighbors: Yeah, it's a good thing I didn't listen to the skeptics or, uh, else we wouldn't have done anything.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Today we're talking with Dr. Harold Woody Neighbors about the accessibility of mental health treatment, what gets in the way of people who need it most, and what his program, Man Up, Man Down is doing to try to bridge that gap for Black men in particular. How do cultural definitions of masculinity keep guys from getting the help they need? How does race affect what happens in the therapy room? And what can all of us, including this white woman psychologist, do to be part of the solution rather than part of the problem?

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Welcome. I'm Dr. Andrea Bonior, and this is Baggage Check Mental Health Talk and Advice with new episodes every Tuesday and Friday. Baggage Check is not a show about luggage or travel. Incidentally, it is also not a show about the prey selectivity of the Venus flytrap. So on to today's show. I'm really glad to have our guest, Dr. Harold Woody Neighbors who took the time to speak to me about an issue that we all can be working towards-- improving the accessibility of mental health treatment, increasing social support, and destigmatizing the idea of talking about mental health and why it can be so hard in certain communities in particular. Dr. Neighbors is a professor at Tulane University School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine in the Department of Social, Behavioral and Population Science. He's also Professor Emeritus at the University of Michigan in the School of Public Health. Dr. Neighbors began a revolutionary program called Man Up, Man Down, with the goal to get Black men, in particular, the social support they need in dealing with emotional problems and to get them connected to mental health treatment, and in doing so to improve their all-around health as well. We had a great conversation about everything from Tough Guy Syndrome to how mental and physical health should be viewed as one and the same, from racism and health disparities to what happens when therapists consider themselves colorblind, and even the differences in male and female friendships. So I'm really glad you're listening. Let's get this started.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: I'm so glad to have you today, Dr. Neighbors. It's wonderful that you can make the time to be here. Welcome to Baggage Check.

Dr. Harold Neighbors: Yeah, well, it's, uh, a pleasure and honor to be here to speak with you today, so I'm looking forward to it.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Thank you. So I would love to start with just how you see the state of mental health right now in general. And maybe there are some signs of hope, perhaps, but I know there are also some concerning signs in terms of accessibility. What are your thoughts from a public health standpoint in terms of where we are with mental health treatment?

Dr. Harold Neighbors: Well, one of my favorite things to say is the more things change, the more they stay the same. So, uh, from a public health standpoint and from the things that I'm interested in, the lack of access to mental health treatment has not gotten better. And particularly within the little corner of my world, the mental health of Black men and the I'll call it underutilization of mental health services has not gotten better, which means it was never good. So it hasn't gotten better. And then as I pay attention to the headlines, uh, because of COVID I'm seeing and hearing lots of signs that things are actually getting worse. In terms of prevalence, of, uh, I'm going to call it distress or psychological distress. The prevalence, the symptomatology that you and I know is painful to people and not necessarily a diagnosis, but just the emotional pain that most of us feel when we're trying to decide, how much pain is this? Can I deal with it myself, or do I need professional help? So Man Down sits kind of in that juncture where we're trying to help people, and particularly Black men, understand, number one, that there is help available. Number two, that it's really okay for you to ask for help. And I can go in depth about why we would even have to say that. Number three, that there are some barriers that you have to overcome in getting professional help, but those barriers that you have to overcome while you're trying to overcome, there's some other things that you can do. And you and I would label those, like, in the general area of social support or informal help. So that's kind of the sweet spot of Man Up, Man Down. But, uh, yeah, I mean, I don't think we're getting any better with delivery. And I think primarily mental health delivery has not been made enough of a priority by the different payment mechanisms. So I'm an advocate of parody. I don't make a big distinction between mental health and what some people call physical health. To me, health is health, and I'm just not making a huge distinction conceptually in my own mind. Although I understand most of the world doesn't look at it the way I do, they're not really seeing this as systemic health. For me, behavior is infused in everything that we do. Well, I understand that there are people out there who talk about behavioral health. I understand what they're saying. But for me, no matter what I do in the health and medical arena, my personal behavior is important. So I can go off track just a little bit. You know, I have type two diabetes. Uh, most of my friends think I have a physical health problem with diabetes, and that there's no emotional or behavioral component attached to my physical health problem, and nothing could be further from the truth. I mean, uh, if my blood sugars are out of control, it affects the way I feel. And if I'm having a bad day, that's bordering on being highly stressed. My behaviors in coping with that, uh, stress will kick in in such a way that if I'm not careful, it's going to damage my fight against diabetes.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Right. It's so true that mental health is physical health and that there are really a lot of scary statistics about how many doctors visits are directly related to increased stress and trauma and emotional health problems. And I think for that reason, it's so important, first of all, that we get physicians on board with really understanding how to steer people towards mental health treatment when that is so clearly needed, but also in communities to try to break down this barrier. Because I think in a lot of communities, there is so much more stigma for the concept of mental health than there is for physical health. And it's much easier to say, I feel off, my stomach is hurting, I'm getting a lot of headaches. I don't have a lot of energy than it is to say I feel down. I don't feel like myself emotionally. Is that something that you find and is that something that you find particularly among men, perhaps?

Dr. Harold Neighbors: I'll say yes and yes. Let me start way downstream and just say I agree with you that the primary care physician is important in this whole arena. Because when people and I'll say when Black men choose to go for any type of professional help, I will call it, it is very likely that they will choose to see their primary care physician if they are fortunate enough to have a primary care physician. One point I want to make is that the way our society has structured the delivery of services, not all of us are fortunate enough to have a regular primary care physician. So that's a problem. And you can picture in your mind that stereotypical picture of an iceberg, and the tip of the iceberg is what we see. And there's usually a huge part of the iceberg underneath the water which we don't see. And so that's the way our medical system works. And so if you think about the tip of the iceberg as those people who have been fortunate enough to somehow figure out a way to get in for treatment, that's all we're getting. So there's a huge number of underserved beneath the water. Typically, many of them don't have the same ability to pay for the services as those of us who live above the water. And then if you think about any particular office, clinic, or system that's above the water, then you understand that that system is only able to serve a subset of the subset that's above water. So that's the general issue. So now, within that context, I agree with you. The individual clinician needs to be involved in the decision making about what kind of help a person needs when they show up. And you're absolutely right. If I show up to my doctor, there's a very good chance as a Black man, I'm not going to open up with I'm feeling depressed, especially somebody my age. I was born in the 50s as a male, as an aging baby boomer. I was raised by men, and a few men in particular, who lived through the Depression, civil rights movement, world War Two, smoking cigarettes, drinking liquor. I mean, there was a certain image of toughness that these guys brought to the table. And as a little boy, you're looking at this and you're picking up the messages that they're sending. And one of the big messages we've learned from our research is something we call tough guy syndrome. Very early on, as far back as I can remember, somewhere around five or six years old, I came to the very clear realization that I needed to be a tough guy, which meant I needed to be a tough boy. So imagine trying to figure out how to be tough, uh, and you're only six years old. That blows my mind right now. At such an early age, I was picking up those messages about the socialization differences between men and women, which feeds into the notion of a tough guy doesn't necessarily need help. A tough guy handles his business, takes care of whatever challenges come his way, and a tough guy learns that there's really no future in showing a lot of emotion or feelings, especially around the other tough guys. This is what it's like to grow up male for many of us in our society, because you're not always going to be appreciated for expressing emotional upset around the other guys, because for many of us, that comes off as being weak. If you're a tough guy, uh, you can't be weak if you're feeling a little vulnerability. The men we have talked to in our research and including myself, we don't really go around broadcasting that vulnerability because of, um, these sort of traditional ways that manhood has been presented to us. All of that is counter to what you and I are talking about today. And that is, how does one get the help that one needs, and, in my humble opinion, the help that one deserves? So I feel that if you're in pain, you deserve access to folks who can help you with that. Uh, so those are some of the barriers that I see to this conversation. And, uh, Man Up, Man Down program has tried to figure out a way to help with that.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yeah. Can you talk about Man Up, Man Down. And that was how I first found your work. It was through learning about this program and really being floored at just how much action was being taken to try to address some of these problems. So tell our listeners about Man Up, Man Down.

Dr. Harold Neighbors: Yeah, so the first thing about Man Up, Man Down is I think all of us are always trying to come up with a catchy label for whatever we're doing, because that's the importance, uh, of the marketing. If you can't figure out how to get people to pay attention and remember what you're up to, then it's almost like it didn't happen. So, for me, it was always fascinating when I think back on how I came up with Man Up, Man Down, and it was because the men that I was most closely associated with, whenever we would get into a conversation about problems, I'll say, like, I'm having a problem. First of all, wow, this must be a pretty damn serious problem if you're actually going to verbalize it to another guy. So, I noticed that, uh, a lot of the other guys would become a little uncomfortable whenever someone would bring up, like, hey, I'm having a problem. I could use some help. Oh, this is different, you know? And then to make a long story short, I mean, it seems like too often the conversation would end with some reference to you need to Man Up. I'm not sure what to do, but you just have to Man Up. And that's what I do. The person who's being asked for help will say, well, when I'm in this situation, I typically Man Up. So I kept thinking about manning up, manning up, manning up. And then out of the clear blue, it hit me that manning up can result in a man going down. And I was interested in research on depression. I mean, that's what I was doing at the time. So, the word down in our culture is a reference to depressive symptomatology. So one day, it just hit me, Man Up, Man Down. And that's what we labeled the program. And if you've seen our logo, we do the Man Down upside down. So when we're wearing our, uh, gear, everybody looks at us and like, what? And then you actually sometimes say, hey, do you know the writing is upside down? We're like, yeah, we actually did that on purpose. Um, so that's where it came from. Manning up can work some of the time, but not all of the time. Sometimes manning up results in a man going down. But in our logo, we have Man Up, Man Down. There's a little circle that goes through those two words, which means that if you're smart and courageous, even though you might be feeling down, you could be Man Up again in no time if you are willing to open up and get the help that you deserve for whatever it is that is troubling you. That's one. Number two, what we learned in our research and what we're trying to say now, is that you are not alone. I think a lot of us guys feel like, oh, I'm the only one that's going through whatever the situation is, and that's totally false. But because we work ourselves into a corner of social isolation, many of the men that we've studied because, uh, we don't want to reveal that we're going through something, we might need some help because we're not super men and tough guys. You start to isolate yourself at a time when you need others the most. And so it makes it look like you're alone because nobody is talking to each other. We men are not talking to each other about these issues. And so you think you're alone when you're really not. And what we've discovered over time is that if you can get a group of men together and start becoming comfortable about what's really going on, very often there's somebody else in the room who either has gone through the same problem or is currently going through the very same problem.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: So tell me about the groups themselves. How do you recruit and what are the typical reactions, trying to recruit? Because Man Up, Man Down focuses on Black men.

Dr. Harold Neighbors: Yeah. So very briefly, we've done manipuldown in a number of different ways. So man at Man Up, Man down started out as a funded research study. And the methodology we employed was the focus group. And so we typically like to have between six and eight men in a focus group. And so we ran, in the original Man Up, Man Down study, we ran somewhere between, uh, I think it was about twelve to 16 focus groups in different cities with Black men. And we recruited into those focus, uh, groups by community advertising, just, uh, on the ground. This is a qualitative study. So we're walking the streets, we're posting flyers, we're just talking to men, and we're saying, hey, we're doing this piece, uh, of research. I'm a Black man. I'm the P. I. for this study. We're trying to get a group of Black men together to talk about mental health and depression. And that worked. It worked. Now we were told it wouldn't work. When I wrote the proposal for this, a number of my colleagues were kind of skeptical. Basically, oh, you can't get Black men to get together and talk about mental health. You can't do that. And so we were like, yeah, maybe we can't, but we're going to try.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Uh, thank goodness you did.

Dr. Harold Neighbors: Yeah. It's a good thing I didn't listen to the skeptics or, uh, else we wouldn't have done anything. So that was one way we recruited. So that was research. We found out a lot of things that I'm not sure we'll be able to talk about today. But the most interesting thing to me was this was not an intervention, this was data collection. But more often than not, at the end of the focus group, one, two, three men would say, this was great. I just really feel so much better than I felt when I walked in here. When is the next meeting?

Dr. Andrea Bonior: And that wasn't even the intent, to provide treatment!

Dr. Harold Neighbors: No. Well, that's what I would say. There is no next meeting. We're not meeting again, this is research. We didn't really come here to actually help you feel better. Now we're interested in the fact that you're telling me that this helped you in some way. And again, this is the point I'm trying to make that we have to be transdisciplinary and everything we do, because I'm not a clinician. I was not trained to counsel or help. I'm an investigator. But I did something that actually helped somebody. So now I'm again running around looking for my clinical colleagues to say, hey, uh, can you help me figure out how to take this focus group thing that we did into a more clinical arena? Because I think we have, uh, found a way that we can help Black men feel better, which is the ultimate point. And so that led to a series of proposals that we wrote. And as you probably well know, not every proposal that's written gets funded. So this is another reason why resistance is the name of the game. You can't take rejection personally or else you'll never get anywhere. So we had a lot of stops and starts, stops and starts. But we eventually got funded by NIH to do a two year lifestyle intervention that was group based, and it focused on adult Black men. That study actually got funded to work on, uh, diabetes and not depression. Uh, uh, but again, behavior is infused everywhere and so is blue. So basically, long story short, we recruited for that study the same way we did for the focus groups, except this was now a group based, longitudinal series of eight group meetings. In other words, we finally were able to answer the question to when is the next meeting? The answer was, the next meeting is next week, and we're going to be meeting with you for eight straight weeks. So that was another version of Man Up, Man Down. And I decided that we needed to do a non research, nonscientific version of man at Man Up, Man Down. And I called that well, we nicknamed Taking It To the Streets. In other words, let's get out of the ivory tower. And we started by going to community, uh, health fairs and just talking to men. And we recruited the men into what we call man demand. No nonsense. There's another word for no nonsense, but I can't say it on air. But it starts with a B and it has an S in there somewhere. No nonsense, man to man dialogues. So one of the things we say to men is take off the mask. Because all of us men live behind a mask, because we don't really want to reveal the true person, because the true person inside is not nearly as much of a tough guy as we have to walk around pretending to be. So we say, can you take off the mask? And can you tell the truth. And in the early days, we use the mirror as a metaphor. We would say, what do you see in the mirror? In other words, when we look in the mirror every morning, there's somebody staring back at you. Most of the time, we don't pay attention to that person. But we emphasize with our men that you really need to stop for a minute and focus on the person looking back at you and seeing if you can understand who that person really is and what's going on with that individual. So we would ask, what do you see in the mirror? So we had a lot of very good stimulus probes to kick off these conversations. And so that's what we did in Detroit and in Flint, which is where I was working at the time. I was in the state of Michigan. These were not research studies. This was like, okay, let's try to see if we can generate some movement around man to man dialogue. Uh, and we did. We did that. So I just decided that this would be great for my own personal life. I have a lot of male friends, I know, but we don't get together with regularity. Like, we see each other when we see each other. And then most of the time, it's about work or it's about sports, it's about automobiles. And it's all that interesting, fun, but somewhat superficial stuff that we like to talk about. And so a very good friend of mine and I started a walking group, and we got a bunch of men together, and we would just walk. And then I experienced a very, very tragic personal loss in my life. I won't go into that right now. Uh, but when I was really the Man Down and I was trying to figure out how do I survive this, the first thing that came to my head was, I need to walk with my friends. So I called two or three of my closest male friends and I said, hey, would you walk with me? And they knew what had happened to me, so they said, of course. So we started this we, uh, called it the BMW Club because I said, well, all of you guys drove BMWs. And I'm like, no, it was actually the Black Men Walking. So that was kind of funny.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yes. I'm so struck by a couple of things there. One is just how important the actual being together and interaction is. Because even before, in the original formulation, when you're just collecting data, these guys were getting together. And that's so powerful. I think the isolation piece is such a part of depression. It's such a part of anxiety and stress and traumatic reactions that just creating these situations where men will be together and where, of course, then it's allowed to actually talk about these things. But the other piece, and I think this speaks to maybe masculinity a little bit, is that uh, in a lot of friendship research, some of the differences between men and women seem to be that men sort of do side to side types of activities together. We're watching the game together, or like you mention, we're doing some sort of thing for our job. We're doing an activity. Women on the whole, and of course, this is a large generalization, but women on the whole tend to be more willing to have face to face types of friendships where we meet to meet, we meet to be able to talk. We meet to have coffee and look at each other and talk. Whereas men in general, it's like, hey, let's do something together. And I'm struck by the fact that there's a middle ground there. So, for instance, with BMW and you all walking, ostensibly there's an activity, but something like walking allows for the talking. More so than, oh, we're just at a sports bar watching the game together and it's really loud and crowded and we're not going to talk about our stuff. I love the idea of creating some sort of activity, but also an activity that is more conducive to actually speaking to each other, because that certainly seems like that's what you were after. It's not just the walking per se, it's the actual being together in the support of your friends and being able to talk if you needed it.

Dr. Harold Neighbors: Yeah, so you've really hit the nail on the head. The no, uh, nonsense. man to man dialogue groups were designed to move away from this side by side thing. You're absolutely right. Uh, that happens a lot with the men I hang out with. We're side by side, we're talking, but it's not quite what man at Man Down was really going for. So the dialogue groups were designed to put us in a circle and talk to each other. So we got that going. And what I was saying in my personal life when we started the BMW group, uh, we were side by side, but we were doing it more than once because it was a walk, it was almost like a walking club. So what we discovered is that when we walked, we talked, we talked side by side. But the more you walk with the same people, the less superficial the conversations become. So the last thing I'll say is that in my own personal life, in a very weird way, the movement to teleconferencing, because all of us got locked down during the pandemic, the movement to teleconferencing opened up a new world for the men that I was hanging out with. And so now we actually get together every other week on screen. And because of the way this is set up, we are talking to each other even though we're not in the same room. We prefer to be in the same room because that's just so much more fun. But for close to two years now, I've had a men's group that meets every other week. And it's amazing how we've been able to slowly and gradually move into deeper level conversations. Not exclusively, but whenever somebody has something going on. And because of our age, we're sixty s and early seventy s. Of course, health is going to be a topic that we always check in on. Typically it's health and family and then how that's going? It's either the R word, retirement and financial planning, um, but it's just been a lifesaver. I'll just say, for me to feel connected even though I'm in a new environment and the pandemic kind of kept me away from people. In fact, we're still distancing not as aggressively as we used to, right? So those are all the things that I'm promoting along with my colleagues, two men. And I do a lot of presentations and talks about it and I always start out with the bottom line for us is that we want Black men to live longer. That's it. Our Black male life expectancy is always lowest compared to the other race by gender groups. So we say, I would like to live as long as my wife is going to live. But right now there's about a six and a half year difference between how long I'm going to be around and how long she's going to be around. I would like to live as long as all my white male friends, but it's more like, uh, they're going to outlive me by about four years. This is that whole health equity movement that we're all trying to figure out. And for me, health equity, I sometimes say, don't say health equity to me until you show me some. And most of the time my colleagues can't show me. I'm always on the lookout for but I can't really find an empirical picture of health equity, which means that the reality of our lives is that we live in a world of health disparity or inequality or inequity. So Man Up, Man Down is ultimately trying to get men to behave. This is on the downstream behavior side. Trying to get men to behave such that we can live longer. And ideally as long as uh, the longest living group, that would be the objective. Now, race and gender and socioeconomic position all factor into this. So I want to be crystal clear that even though I am a psychologist by training, I'm a social psychologist, I'm never going to, um, ignore the importance of behavior and individual decision making. But I also understand that all of that behavior and individual decision making takes place within a larger socioeconomic context. And so it's not always about individual health literacy or individual motivation. I'm actually not a big fan anymore. The word resilience, but that word became so popular that it was almost communicating that if you're not doing what you're supposed to do, then you're not resilient enough. And I'm like, my thing is, hey, could you make it. Easier for me to behave myself. And that's a structural problem. So with diabetes, yeah, I can work really hard not to eat too many carbs. But I really wish the food industry would make it easier for me to not eat food that's full of sugar. I wish the food industry would make it easier for me to not eat food that's full of sodium, because salt and sugar are enemies to us all. And we know sugar especially can be very addicting.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Hey, I just had an episode on that, actually, last week with Dr. Nicole Avena!

Dr. Harold Neighbors: I'm going to go listen to that.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: And you're right, this is all connected. And I think when we talk about services and all of the things in terms of mental health that we would like to be able to have for folks and getting people into treatment, I think one of the first things that comes to mind, and we're really facing that now, is that when we look at the accessibility of care, we can't ignore the fact that there are a lot of white female psychologists like me. I mean, this is no doubt part of the problem in the sense that we don't have necessarily the amount of mental health care providers who actually look like the people that would be trying to seek care. What can a white therapist, a white female therapist like myself, and again, there are so many of us. How can we be part of the solution rather than the problem? And how can we really allow more diversity to be not only in the field, but in the types of care that we offer?

Dr. Harold Neighbors: That is the question. I'm glad you asked me that, because in addition to, um, working for Tulane and University of Michigan, I'm also doing, uh, some consulting with a tele mental health business called, uh, hurdle Health. And again, I'm consulting primarily in my role as a research scientist. And I have colleagues who have much more expertise in this issue than I have. Uh, but I do have some awareness and understanding of, uh, your question. And my awareness comes from not only the research and reading that I've done, but also from my personal life as a consumer of mental health services. So the first thing I'll say is that if I were elected president, I never will be, but if I were, my first executive order would be universal, lifetime, mandatory psychotherapy for everything.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yeah, you're not getting a lot of.

Dr. Harold Neighbors: No, I'm not on that platform. Uh, but that's how much I believe that this is such a healthy thing to do for all of us. So that's the first thing, uh, to put that policy in place. I need many more therapists, and I think that's the point you're making. And because we're interested in health, equity and diversity, we need therapists of all colors. So I'm a big proponent of just getting everybody trained up. Male, female, Black, brown, whatever colors you want to mention. We, uh, need more clinicians doing this work. Now, to get to your point, what can you do? The research that we're working on right now with Hurdle Health is designed to answer that question by developing what might be called. There's a lot of different terms out there. Some people would call it, um, culturally sensitive training, some people would call it culturally competent training. But the Hurdle group that I'm working with, the way we're talking about this, is developing training for everyone to be culturally intentional. And all we mean by being culturally intentional is to give clinicians the tools that they need to broach the topic of race, ethnicity, and culture with your clients. And broaching is a term that refers to a model that comes out of Johns Hopkins by Dr. Dave Vines, who has been working on this broaching concept. And she's the expert in that area. And so we're trying to take her work and package it in a way that becomes much more tailored to adult Black men in therapy. So it's okay if somebody looks like me, but that's never going to be enough. So one of the things I say is, if all you know about me is what I look like, then you don't know much about me at all. So you really need to sit down and talk to me, uh, to really understand what's going on. So if I have you as a therapist, you're white woman, I'm a Black man. If I have you as a therapist, I'm not going to automatically assume that you can't help me. That's going to be a conversation. But as a consumer, what I have found is one who has been in mental health counseling. What I have found is that my non, um, Black therapists don't always broach or bring up the issue of race. If I could really pin it down to one thing, I guess it's not the way they're trained or maybe they're feeling uncomfortable about. I don't really know. But we need to get inside that. So that's my answer to your question. We need to, um, identify the elephant in the room. Now, that's on the therapist, but I think it's also partially on the client, depending on how much pain the clients in. But I know if I go back into therapy again, or I should say when I go back in again, uh, I'm going to be much more assertive if my therapist doesn't bring it up, I'm bringing it up. I'm going to walk and say, look, did you notice I'm a Black man born in the 50s. I'm sure they're going to be like, what's wrong with this guy? I'm basically going to say, look, so many of my insecurities and problems and the pain that I experienced is because I was in that generation of Black children who were one of the first to actually go to a white school because we had a policy of integration, desegregation and integration. Although the integration got going a little faster than the desegregation because I grew up in an all Black neighborhood because we were segregated. But I lived in an area, uh, where I went to a predominantly white school, and that started in the second grade for me. So I'm just going to open up to my third. Like, if I can get you to be my counselor, I would say to you, hey, we need to talk about what it was like for me to be in the second grade and walk into a classroom and look around, and it was all white. But I came from a neighborhood that was all Black. And in the all Black neighborhood, we were told that white people do not like us. They don't want us around. They actually hate us. There is this thing called racism. Now go to school with the white kids. I'm like, Wait a minute, hold up. Uh, do I really have to? So I'm in that classroom trying to figure out, how do I do this? And I can remember the feeling of anxiety, and I always feel anxiety in my stomach. So I think that's my answer. I think it's one of more optimism. But we do need the money to train the people, but then we need to have the models like Broaching say, here's another, like, just check it out, and you and I might find that, hey, race is not even an issue for whatever I'm here for. But it could be.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yeah. And I think there is fear. I can't speak for all therapists, but I certainly can imagine and I've had this myself, certainly sometimes, the discomfort and fear of, uh, first of all, am I going to make this an issue? If they weren't thinking it was an issue. But it's an issue in the room that needs to be addressed, because if it's not addressed, then it is an issue. And I think also there is a concern may be that, what if I am not the right fit for this person? And now I'm highlighting it? But I think, again, that's kind of an unfounded concern, because better to actually be able to see if that is or is not the case so that then the client can be able to act on it.

Dr. Harold Neighbors: Yeah. Because I'm not a clinician, I don't really know what's going on on the other side of that desk or table or whatever separating, um, us. But when I put on the hat of a researcher, what I'm finding is that we've been doing many more studies on the clients and the patients than we're doing on the actual therapist. So I don't know if a white therapist is feeling uncomfortable if they have a Black client. I just don't know. But we should find out. And if that's part of it, we should be studying more. How can we help the clinicians do the job that they signed up, uh, to do. And that's why I'm really enjoying this study I'm working on now with Hurdle, because we're trying to figure out how do we give the clinicians the tools that they need to do this complicated job? And you're right. You don't want to ask that question in the wrong way. You don't want to broach the topic of race in the wrong way, because you could blow the whole thing. So you've got to be sensitive about it. But the bottom line is, if it turns out that this is not a good match between the two of us, for whatever reason, that's no slight on the therapist. That's just like, hey, this isn't quite the match we were hoping for. But I think a lot of clients who go into therapy don't understand how much more assertive they can be and trying to even shop around for sure. So we're trying to get that word out.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Absolutely. So I'm thinking, obviously, you had certain experiences growing up in the 50s that were fundamentally different than some of the experiences of kids growing up now, including young Black boys growing up now. And I wonder, how do you see some of the recent cultural forces working? You know, are we seeing changes in stereotypes in terms of manning up and being super tough? Are we seeing any impacts, for instance, of Black Lives Matter in terms of how we can look at these systemic inequalities in a way that perhaps might lend to more discussion about mental health issues? Do you see any major differences happening in, for instance, the way that a kid is being raised now versus how you were a couple of generations ago?

Dr. Harold Neighbors: It's hard for me to answer that question because I don't work with children, adolescents, but I do see some differences that are curious to me. One is Black. Uh, Lives Matter and George Floyd. In my observations, that stimulated a much broader conversation about the thing that's responsible for all of this race is the child of racism. So for most of my career, racism was the other R word. I was too young to be concerned about retirement, so the other R word was, uh, racism. But we knew as Black social scientists, that was just not a popular term to bring up in mixed settings. By mixed, I mean Black and white. But when we were in an all Black research setting, I mean, most of us were just really working on that. So now if you hang around long enough, four or five decades, you'd be amazed at how things change. And so I've noticed just a lot more conversation about racism. So that's the first thing I see. And now I'm actually in cross race conversations about racism. So I have white colleagues I talk to about racism. When it first started happening, I was like, what the hell is going on here? This is not the way this was supposed to turn out, and that has changed. M, so that's one thing I see, and I think that's a good thing. So that's happening on the public health, uh, structural determinant level. So we are talking a lot more about systemic racism. But what is really fascinating that down on the ground downstream in the clinical world, so many more of the clinicians that I interact with are trying to understand what we call unequal treatment, which is the clinical version of population health disparities. And when I first started my career, the only clinical folks who are really interested in race, ethnicity and culture were clinical psychologists. You know, the helping professions on the quote unquote mental health side, we were always obsessed about that. Even parts of psychiatry, like most of my psychiatry friends, are cultural psychiatrists. That concern about race, ethnicity and culture has broadened within the field of medicine. So, uh, I'll just say that it's very broad in comparison to what it was before, and I think that's a good thing. So the issue there, the issue is color blindness, the pros and cons of people who are telling me within a clinical context that, hey, I'm color blinding.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yes. And that might be for some therapists, too. That might be exactly the problem, why they don't bring up race as well as they have some kind of mistaken notion that they're not supposed to see that in the room.

Dr. Harold Neighbors: Yeah, I mean, I think that's it either is it mistaken, number one. Number two, is it relevant to the situation? And then number three, if it is relevant, how do I figure it out? But this whole dynamic of structural racism and clinical treatment is causing some cognitive dissonance on the therapist side, because in my experience, a lot of time, if I show up talking about structural racism in medicine, the clinicians hear me calling them a racist. And so then I have to say, no, I don't even know anything about you. I'm not saying you're a racist. We're just trying to figure out how structural racism works its way into different areas of society. So let's talk about that. But then I also say, well, since you brought it up, I'm just curious, are you a racist? Now that's kind of tongue in cheek, because nobody's going to say yes to that. Well, I shouldn't say nobody, but most people are not going to say yes to that. But typically what I hear is, uh, is it an issue? And they say, no, it's absolutely not an issue because I'm color blinding. I treat everybody the same. So that goes to the point you're making is that a good thing or a bad thing?

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Right?

Dr. Harold Neighbors: Is everybody the same or are people different?

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Right?

Dr. Harold Neighbors: That's a philosophical dilemma. But on a group basis, because of the way our society was structured, more often than not, the color of one's skin is an initial signal that, oh, you've lived a very different life than this person over here who has a different color because this is the United States. I mean, this is the legacy of enslavement and anti Black white supremacy that is the foundation upon which our system was built. Uh, right. So if you know that, then it does make sense to say, hey, I am kind of looking around for people who kind of look like me. And my thing is that's okay, but don't stop there. Like, you got to go up to that person who looks like you and have a conversation, and you need to go to the person who doesn't look like you and have a conversation. So that's the point you're bringing up that if we happen to come together in a therapeutic situation, if I walk in and I'm like, damn, she doesn't look like me at all, that doesn't necessarily mean I walk out of the room, right? We have a conversation and then, you know, we say, hey, yeah, I mean, it's not going to work, or yeah, so I've had white therapists and they've been very helpful. I've had Black therapists, they've been helpful. My white therapists have not been helpful in the same way, mhm because they don't want to talk about racism and white supremacy. It's complicated, but it's doable because the thing that has changed for me is that there's a broader conversation happening about that. I can actually say racism out loud. And for the past year or so, I've been actually saying white supremacy out loud, which still boggles my M mind. I can get up in front of people and say that. Now, I know it's a selected audience and I know there's some people don't appreciate hearing it, but they're not going to say anything. But at least it's percolating out there. And we're all very well aware of the vicious battles that are being fought around critical race theory, M, and that keeps us grounded and that this stuff is politically controversial. Yes, this is really a political issue that is working its way into health and science. But my position is that health is a political process, for sure.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: And so there are really some glimmers of hope that when these dialogues are opened up, that it can really help people have the difficult conversations that they need to have on a macro level societally, which can hopefully affect some change individually and allow people to say here is what I've gone through, or here are the problems of society and here's how I deserve some support. I deserve some help. And here's some of the ways that there have been barriers for me to have actually spoken up, or how it doesn't seem as culturally acceptable for a Black man, for instance, to ask for help. And I'd really love to continue this conversation sometime because I think there's so much here, but I also know you have to go. But I really appreciate you having taken the time today. And where can people follow some of this research that you're doing?

Dr. Harold Neighbors: The best place, I'll just say I guess the most recent place would be in the journal Social, uh, Science and Medicine, where we recently published a, uh, commentary on structural racism. The other place is a recent issue of The American Psychologist where I wasn't the lead author on that paper, but some of my colleagues at University of Michigan took the lead to write a historical overview of the research program that we all came out of at, uh, the University of Michigan. And our mentor was a psychologist, uh, James S. Jackson, and he recently passed away, sadly, but he was a giant in the field and so many of us owe our careers to his mentorship. And we did a paper, it was led by, um, dr. Robert Joseph Taylor and Dr. Linda Chatter, but there were multiple authors. Uh, that's another place where they can kind of get a feel for what is, uh, going on. I don't really have a website dedicated to mendown because I am somewhat semi retired and if I were still at the university, then I would have the whole big thing. But right now I am, uh, really looking to mentor early career investigators to help them navigate the academy because those are rough waters. And, uh, I'm looking for other folks who are interested in moving this Man Up, Man Down idea along. It doesn't have to be named Manipul down. It can be named anything you want it to be named. Uh, so I'm doing a lot of networking in that way, and then I'm doing a lot of speaking. So I'm really thankful that you reached out to me, but also I just show up and give talks. If you're a university professor, you're programmed to talk.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: That is true.

Dr. Harold Neighbors: Uh, but I'm excited about this particular issue and I just want everyone to hear about it.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yeah, well, I'm so glad that you were able to join me today. And I think a lot of folks really are looking for these roadmaps of how can there be some change, how are folks working on these types of issues to be able to get people the help that they need? Because I do think that for Black men in particular, there have been so many barriers to just talking about mental health, but also to actually receiving treatment. And I really commend you for the work that you're doing and trying to lower those barriers. So thank you again, Dr. Neighbors.

Dr. Harold Neighbors: Thank you. And I'll just close by saying that the structural changes that we need in our society surrounding racism, those changes have moved very slowly, m much more slowly than anybody would have imagined back in the 50s when we had Brown versus the Board of Education. So in the meantime, Black men, but Black people in general, will have to continue to figure out how we are going to cope with the unfairness that is injured into our societal arrangements. So it's going to take a long time to change racism. So in the meantime, sadly and unfortunately, it's going to be up to individuals to respond to the structural inequalities. And that's why, at the end of the day, I can't spend all of my time on public health interventions. Because I do want to come downstream to work with clinicians to figure out how we're going to help individuals who are the inevitable casualties of a society that decided to become obsessed with skin color. To create groups based on phenotypic characteristics like skin color and hair texture. And then the worst thing of all is to create a hierarchy based on those categorizations. That is the problem, creating a hierarchy of groups and then getting to work on putting together a financial structure that is going to really make some people a lot of money, leave other people out. So a lot of that is still in place. And because of that, there will be inevitable casualties of those differentiations. And that's why clinical work is so important. We need clinicians. We need more clinicians, and we need clinicians who are willing to broach all of these topics, including race, ethnicity and culture.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yeah. So sort of a call to action for all the actual clinicians that are listening today for us to do our part.

Dr. Harold Neighbors: Also a call to action for our government officials to make racial justice even more of a priority.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yeah. Well, thank you again so much, Dr. Neighbors. It's been a true pleasure.

Dr. Harold Neighbors: Well, thank you. I look forward to talking to you again.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yes, likewise.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Thank you for joining me today. Once again, I'm Dr. Andrea Bonior, and this has been Baggage Check, with new episodes every Tuesday and Friday. Join us on Instagram at Baggage Check podcast to give your take on upcoming topics and guests. And why not tell your chatty coworker where to find us? Our original music is by Jordan Cooper, cover art by Danielle Merity, and my studio security is provided by Buster the Dog. Until next time, take good care.