Shownotes

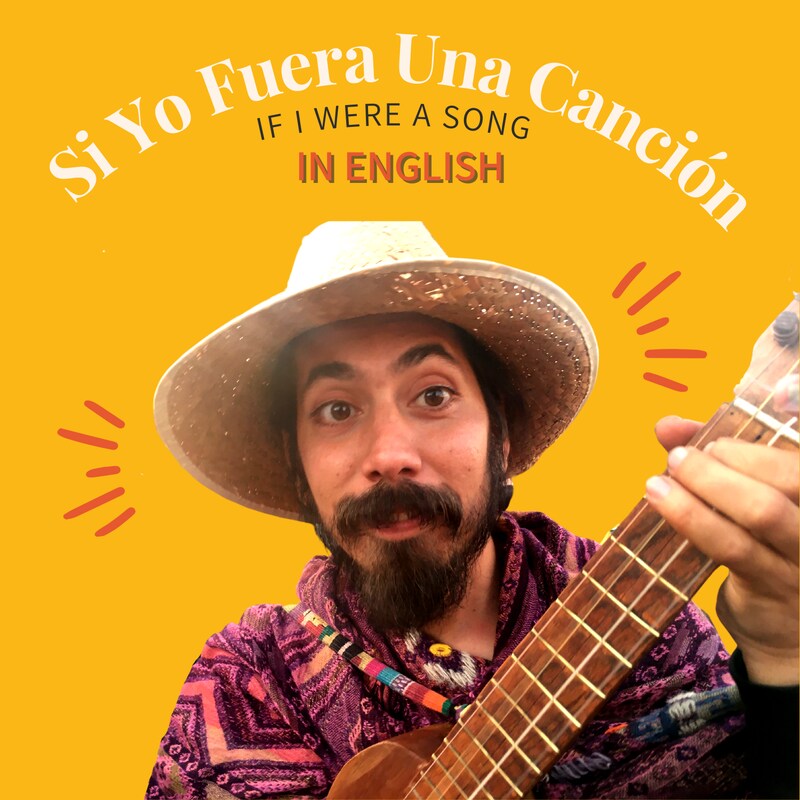

A musician and community activist, Luis speaks about renewing our connection to the Earth; rivers; and how to move on from the losses provoked by violence and injustice.

La obra de Martí está en dominio público. Un portal al acceso general se puede hallar en https://es.wikisource.org/wiki/Autor:Jos%C3%A9_Mart%C3%AD

Martí’s work is in the public domain. This is a general access portal.

Como hombre de letras // As a man of letters

in English:

- Schulman, Ivan A. (1989). «José Martí». En Solé/Abreu, ed. Latin American Writers. 3 Vols.(Nueva York: Charles Scribner's Sons) I: 311-319.

en español:

- Henríquez Ureña, Max (1963). «XXXVII: José Martí». Panorama histórico de la literatura cubana 1492-1952. 2 tomos. Tomo II. New York: Las Américas. pp. 210-231.

Como figura política // As a political figure

en español:

Ward, Thomas (octubre de 2007). «From Sarmiento to Martí and Hostos: Extricating the Nation from Coloniality». European Review of Latin American and Caribbean Studies (en inglés) (83): 83-104.

in English:

- Ramos, Julio; Blanco, John D. (2001). Divergent Modernities: Culture and Politics in Nineteenth-Century Latin America (en inglés). Durham: Duke University Press. pp. 151-159, 251-267, 268-279. «Véase particularmente "Marti and His Journey to the United States", "'Nuestra America': The Art of Good Governence", The Repose of Heroes: On Poetry and War in Marti"».

LOS RÍOS CANALIZADOS DE LA ZONA DE LOS ÁNGELES, Y LOS ESFUERZOS DE RESTAURACIÓN

CHANNELED RIVERS IN THE LA AREA, AND EFFORTS TOWARD RESTORATION

Sitio Web de la ciudad de Los Ángeles (en inglés):

http://lariver.org/blog/la-river-ecosystem-restoration

Friends of the LA River: https://folar.org

Proyecto de la Herencia Salvaje de la Sierra de Santa Ana, https://santaanamountains.org/hogar.html

Friends of Harbors, Beaches, and Parks

ECOLOGICAL AND SOCIAL VIOLENCE IN VERACRUZ

VIOLENCIA SOCIAL Y ECOLÓGICA EN VERACRUZ

in English:

Crisis Group: “Veracruz: Fixing Mexico's State of Terror”

https://www.crisisgroup.org/latin-america-caribbean/mexico/61-veracruz-fixing-mexicos-state-terror

Santiago, Myrna. “Black Rain: Veracruz 1900–1938.” Berkeley Review of Latin American Studies, Spring 2007 https://clas.berkeley.edu/research/energy-black-rain-veracruz-1900%E2%80%931938

en español:

Chenaut, Victoria. “Impactos sociales y ambientales de la explotación de hidrocarburos en el municipio de Papantla, Veracruz (México)” e-cadernos CES #28 (2017)

https://journals.openedition.org/eces/2433?lang=en

Lazos, Elena, and Luisa Paré. Miradas indígenas sobre una naturaleza" entristecida": percepciones del deterioro ambiental entre nahuas del sur de Veracruz. Plaza y Valdes, 2000.

ARCADIO HIDALGO

Gutiérrez, Gilberto, y Juan Pascoe, coordinadores. La versada de Arcadio Hidalgo. Editroial Ficción, Universidad Veracruzana. 3a ed., 2003

Transcripts

Greetings to all. The interview you are about to hear is a re-staging in English of my original interview in Spanish with Luis Sarmiento. Luis is played by the voice actor Wesley McClintock.

Luis is a Santanero, still young, who is a musician, poet, activist, organizer, and, as we shall hear, impassioned advocate for honoring the Earth and the people who live in harmony with the Earth, those who don’t necessarily form part of the great narrative—some say it is a tragedy—of modernity.

Luis is also a natural orator. He presents hImself very completely in the interview, so he doesn’t need more introduction from me. Let’s get to it!

ELG. Good afternoon. I’m here with my interviewee, Luis Sarmiento, on the line…Luis, how old are you?

LS. Oh my God!....uhhh…I’m…33. I think.

I’m starting to lose count, honestly.

ELG. Well, 33, 34, what’s the difference really?

LS. Well, yeah.

ELG. And what is your job or profession right now?

LS. [Whistles] A little bit of everything. I mainly do community organization. I’m a musician; I spend some time with community media, you know? a little bit with radio production; a very little with video; but everything has to do with community organization.

At the moment in Santa Ana, we’ve focused a lot on economic projects and projects where we’re fighting as a community for spaces, for land, you know? where we can develop projects, whether it’s urban agriculture, or even looking at the possibility of building housing for the community; or a marketplace.

We have different ideas aboout how to go about getting space for community development. It’s more or less this that I’ve been doing in recent years.

Also, forming networks with community organizations in Mexico, above all in Veracruz, Oaxaca, in Mexico City, where I’m from, also; wherever there’s a group, there we are! everywhere, building this network of community work.

I grew up here, and this is where I’ve ended up working, and here we are. Here in Santa Ana.

I would mention the Centro Cultural de México. It’s a space, an organization, to which I owe a big part of my development as a human, and in my work, to the Centro Cultural.

Right now I also work with another organization that we’ve started here in Santa Ana, which is called THRIVE Santa Ana, which is, it’s just an association of community land holdings. That’s the group where we’re trying to get pieces of land to do community projects, using a model called the Community Land Trust.

ELG. Mmm…

LS…and so, those are the main organizations. Also there’s our community radio, here in Santa Ana: Radio SanTana. I take part in that too.

INSERT #1

’s where I met Luis, around:El Centro Cultural de Mexico is a community space dedicated to cultivating and exploring the intersections—sometimes collisions—among the many cultures that call themselves Mexican, and the realities of urban life in the United States. For over 20 years the Centro has offered community classes in music, dance, and art, and it has become an axis for community organizing on behalf of and by migrants and Santa Ana residents, many of whom are economically disadvantaged.

Everything is a bit up in the air because of the pandemic; like everyone, we at Centro are seeking new ways to make community without meeting in the flesh.

Radio Santa Ana, based at the Centro, broadcasts at 104.7. Community radio is perhaps one of the most promising avenues of response to the challenges of social distancing. The station is also the promoter of this show. Every episode of our podcast is first broadcast on Radio Santa Ana.

Links to all the organizations that Luis mentions appear on our website, for those who want to know more.

ELG. Now I’d like to ask you a question that’s—

LS. Elisabeth! There’s a helicopter passing over. Maybe you want to wait a sec because of the noise.

ELG. Oh, yeah. Those wonderful helicopters…[laughs] We have put up with them here, too. A lot.

LS. Yup.

ELG. Someone told me recently that every time the Santa Ana Police gets out a helicopter to circle over a community, it costs us, like, ten thousand dollars.

LS. Yeah, that’s right, that’s right. I think I’ve heard that same figure.

ELG. Uh-huh. What a thing…

LS. Right? –it’s gone now.

ELG. OK. So the question is: “Where are you from?”

LS. Ummmm…well, thanks for the question. I think sometimes about the poem by José Martí, that says,

I come from everywhere,

and toward everywhere I go.

I am an art among the arts,

and in the woods, as woods I go.

INSERT #2

olitical activist, lived from: .” Martí published them in:[….]

Now we return to Luis’ answer to my question, “Where are you from?”

LS. And well, more specifically—I was born in Mexico City. My mother is from there, from Mexico City. From Iguala, Guerrero, on my grandmother’s side, and from León, Guanajuato, on the side of my maternal grandfather, Jose Luis…a little while ago my Mama was remembering a rhyme that her father used to sing to her when they were going to bed as little children.

[…]

LS. And so, on one side I think I’m…I’m from there, you know? I’m from a very urban experience, right? people who had roots in the family, right? Always in my mother’s family, we would say that the two lessons that most stuck with us from my grandparents were: to stay together, and to enjoy life. And so, that’s my heritage…on my father’s side, my father is Chicano, from El Paso, Texas. My grandmother, that is, my grandma, was born in Fort Worth, Texas, if I’m not mistaken.

ELG. Mmm.

LS. And my Grandpa, from Juárez?—in fact, I’m not sure where my grandfather was born. But they are from Juárez, my grandmother and grandfather are from Juárez. They lived in a time where going to and fro across the border, I think it was something quite common, you know? Living on one side, working on the other, you know?

ELG. Yeah.

LS. –or to make an appointment to get your hair cut in Juárez, you know? Things like that.

And my Dad, my father, well he grew up in the Chicano Movement, you know? in the social movement that there was here, that is…well, at some point they came here to Santa Ana. In the 60s, if I’m not mistaken.

So my dad also grew up here in Santa Ana. And so, well, I’m from here too, from Santa Ana. I guess I mostly grew up here. And so, with this mixed identity, right? with this identity where I feel like I’m Mexican, but living here, and with…well, with luck, right? with this great privilege that I’ve had, of being able to spend time in Mexico, I’ve been able to really ground my identity as a Mexican.

ELG. Mmm.

LS. And that’s given me a lot of strength to live in this country, and to face the racism in this country. Which I can tell you I have had to do, you know?

ELG. Mm-hmm.

LS. That is…I can also acknowledge that I had the great privilege of studying, you know? going to University, right? having a formal education, which helped me a lot. Not so much for the education it gave me as for the opportunities I had, you know? But more than anything, I think it’s been this connection with my community and with my culture that’s been, like, a really strong source of knowledge and personal growth for me.

So that’s where I’m from!

ELG. Yeah, yeah. Okay…Let’s go to the song you chose to express or represent this state—such a complex state!—of roots or origins, that you are living. You chose the song, “Tú que puedes, vuelvete,” [that is, “You who can, come back,”] by Atahualpa Yupanqui.

LS. Mm-hmm.

SONG CLIP #1 – Atahualpa Yupanqui, “Tú que puedes, Vuélvete”

ELG. Something that occurs to me after listening this time is that. in addition to being, I think, a great poet, he was an impressive guitarist.

LS. Yeah.

ELG. He plays with a…I don’t know…a fluidity, that I like a lot.

LS. Yeah, I like it a lot too. I can’t say I know the history of Atahualpa Yupanqui very well, but what I’ve seen in interviews and in, like you say, in his poetry, and his way of playing…well, I love it, and it has…I don’t know…I’m really inspired by the connection he has, with the landscape of his country.

ELG. Mm-hmmm…So, how did you come to know this song? How did it come into your life?

LS. Good question [chuckles]. I’m not sure when I first heard Atahualpa Yupanqui’s music , but…itt did have to do, in one way, with a friend, a girlfriend, we got to travel together through Northern Argentina, and we got to know a little bit of those territories that Atahualpa Yupanqui talks about a lot.

What I understand is that Atahualpa was, like, oone of the very early representatives of, not just traditional music, folk music as they call it—music of the people, you know?—in the social movements, movements for raising up the experiences of peasant people, you know? working people, you know? And then afterward came Mercedes Sosa, and even from Chile, you know, like…Violeta Parra, Victor Jara.

Atahualpa, as I understand it, is, like, part of this movement, bringing forward these peasant traditions of music.

I don’t know if I’m right about this, but I think he was Classically trained. But he devoted himself to bringing forward, well, the experiences of country people, you know?

ELG. Mm-hmm, mm-hmm…

LS. And I remember a conversation that I had once with a friend in the Collective, Saél. We were talking about how, in the history of social movements, well, often we’ve seen this alliance between city people and country people.

ELG. Well, Atahualpa himself, as far as I know, was not a peasant at all. He was from the middle class in his country, I think. So this is another example of exactly this phenomenon of alliances, a little fragile but with good intentions, I think, between the bourgeois and those who live on and work the land.

LS. --And sadly, in the history of social movements, country people give a lpt to these movements only to be disillusioned in the end, and in a certain way, betrayed by the interests of that petty bourgeois class of city people.

How can we get past this? How can we manage to create a real alliance, you know? one that benefits not just the petty bourgeois, but really raises up the people? –in this case, peasant musicians, people who are making music in their native places? And how can we build a movement that really looks to the people who are maintaining the roots, you know?

So that’s really the challenge. People like us, city people, I think we have a pleasure and a responsibility, and I think the main responsibility is toward the root, you know? toward supporting people who remain in their native places, that is, maintaining their culture, not just music but the whole lifeway they maintain.

ELG. Well you’re touching on a lot of important points. It’s that I, just like you say, I enjoy the great privilege—really it’s a set of privileges—of having been an urban person with good resources and a great deal of education, musical training, and so on. I agree strongly with you, that we who enjoy these social, socio-economic advantages, we have a duty, I think, to learn to listen to all, all the others in the workd, who haven’t enjoyed these privileges. And that act, the simple act of listening, it’s fundamental to music. And that’s the reason for this project, this program, and this interview!

In a certain sense, Luis, we share some really big goals, I think.

I’d like to just return us for a moment to the song, because some passages in the poetry caught my attention. Most of all this one of…well. It’s that the river he’s singing about, that he’s talking about, it’s…it’s a sad river.

CLIP #2 – “Tú que puedes, vuélvete”

ELG. I want to ask you: how is it that that sadness—the flow of Time and the impossibility of returning—how is it that it represents or expresses your sense of roots, your sense of where you’re from?

LS. Yeah…I think I identify with the experience that many migrant people have, of the nostalgia to return, and…probably everyone lives this in their own way.

I also think that for me, it was very impactful in Mexico, being able to come to know living rivers, for example, in Southern Veracruz, or, traveling further South, seeing these rivers that are, well, they’re alive. In comparison with the river we have here in Santa Ana.

ELG. Ay, ay, ayy. Yeah.

LS. It’s really sad when you compare it, right? It’s a river that was put into a paved channel.

ELG. It’s an imprisoned river.

LS. Yeah.

ELG. –in a channel that’s like, 22 miles long, of pure concrete.

LS. Exactly.

ELG. It’s the saddest thing I’ve ever seen.

LS. Similar, similar to this, maybe—so for people who don’t know the Santa Ana River, it’s similar to how the Los Angeles River looks, you know? They’re rivers that I imagine that in their day they were great rivers, you know? And even the historians of this region, who’ve dedicated themselves to keeping the history of the flora and fauna, and obviously of the peoples, right? of this area, like, the history of that river that was paved is also representative of what happened to the original life in this region.

ELG. Yeah.

LS. So then, for me the nostalgia to return doesn’t just represent, well, going back to Mexico in my case—it also represents returning, well, to a way of life that I’ve been able to see in other places, that is. a life that’s more in accord with the natural world, you know? A life that’s more in accord with Nature, and the life it contains.

ELG. Ah, yes, yes. You’ve given it completely another angle, but a really provocative one…You know what, Luis? There’s a part of the Los Angeles River that they’ve let return to its natural condition as a river, with the plants, and the mud that accumulates over the concrete, and the coourse of the river in that part has its curves, its meanders that are natural to rivers. And an astonishing variety of flora and fauna has returned. These imprisoned rivers that we have aroound here still have the will and the capacity to return to being themselves.

INSERT #4

In the: In:The Santa Ana River is quite a bit longer, and has a bigger drainage basin, than the LA River. Upstream in Riverside County, there are still some sections of it that are more or less in natural condition; but downstream, its last 22 miles, including the part that passes through the city of Santa Ana itself, are a desert of pure concrete. It really is a “sad river.” Once again—you can find links and read more on our Website.

ELG. So, okay, maybe with this let’s move on to talking a little about your other song, your second song, the one that expresses your hopes for the future.

SONG CLIP #2 – “MARAP,” Colectivo Altepee with Sector 145

ELG. Do you want to tell us a little about how you came to know the artists that are performing here? And a bit of your history with this group?

LS. In the song I chose, it’s that…it’s a collaboration between the Colectivo Altepee and a group of young people [that call themselves] Sector 145, they’re young rappers from Sayula de Alemán, there on one side of Acayucan [in Veracruz], they’re young people who rap in Popoluca, you know? Popoluca is one of the cultures that descend from the Olmec culture, right? They’re descendents oof the Olmec people, one of the oldest cultures on our continent.

ELG. Yeah.

LS. And these young people are rapping about their territory, you know? about their pride in their land.

When I think about “Where are we going?” –I learned more than anything from communities in Mexico that have maintained a path, to defending their culture, defending their identity, defending their territory.

And I also think, with what we were talking about just now with the Santa Ana River—also about the experience of the original peoples from here, about the Ajacchemen community, the Tongva community.

ELG. Mmm.

LS. And I feel like, “Where are we going?” It’s like a moment where—and, okay, I didn’t invent this phrase, right?—but this idea that, like, it’s the time of the people, you know? A time where we’re waking up as a people, and honoring the experience of persons who have maintained that history, who have maintained that connectioon with the Earth, who have maintained that connection with Nature.

And if you look at the world right now, we need that urgently, right?

ELG. Very urgently. Yes.

LS. And for me, the Colectivo Altepee wasn’t just a really, really great example of that work, but also it also a group of people who invited me, they said, “Hey, come here and work with us.” And in the context of doing that work, well, I met a lot of people that I admire enormously to this day, for their commitment.

Sadly, one of the young people who’s rapping [in the video], Tío Bad, he was murdered.

ELG. It’s a horrible thing. But it also turns out to be a kind of commentary on the difficulty of realizing those hopes, right? Because there’s a lot that’s against it.

LS. Yeah.

INSERT #5

Being so rich in natural resources, Southern Veracruz has been subjected to centuries of ecological violence. Sadly, in recent years this violence has once again become social as well. Poverty and desperation, governmental corruption, the cynical taking advantage of these conditions by drug cartels, and the eternal response of the Police, have come together to make this region really dangerous for its residents. This is the violence that took the life of Tío Bad, and too many others.

ELG. So, this song can only be found on YouTube, with a video, a really pretty video, I think. But for those who are listening, you have to imagine those images of greenery, the leafiness of Veracruz. And one of the beauties of the video is that right at the end, you see the face of that young man, Tío Bad, he raps with a lot of intensity, but then his face opens up in a smile when the music ends. It’s, it’s…something.

LS. I know that we could stay with the sadness, we could start thinking about how many people we’ve lost, right? People like Josué, like Tío Bad, who fought for a better life, not just for themselves but for their community.

There are so, so many examples of valuable people that we’ve lost. However, I think the main thing is to learn, right? from that commitment, from that inspiration, and honor the memory of those people with whatever we can do, you know? each one of us from wherever we are, with the resources we have at hand, with the music we can make, the words we can share, with projects…

I think that, like you said a minute ago, we share a mission or a vision that’s, well, it’s pretty big, isn’t it? That has to do with honoring the work and the knowledge of communities a persons who have kept a culture in harmony with Nature, with the Earth, a culture of caring for the Earth, a culture of caring for ourselves as a community.

I also like to think that that’s the path to follow.

ELG. Yeah. And it occurs to me that the strongest, most solid hopes, the ones that have the best chance of being realized, you know? are the ones that are rooted in…well, often, in pain. Or they come through the sacrifices of other generations. It’s that there is, there is this connection between the future and various pasts, some of them very painful.

LS. Yeah.

ELG. And, well, it’s the presence of that young man, visible and audible in the video, rapping, reminds us a little bit of that fact, I think.

I was also struck by the verse that Gemaly sings:

“El que tiene pa’ comer

se olvida dél que no tiene…”

[which translates to, “He who has enough to eat/forgets about the one who doesn’t”]

--It’s funny, because it’s another way of delivering a text, delivering a feeling, a poem, singing in this way. She isn’t rapping, and also it’s a verse from another generation…but it fits perfectly, and it really brings out the rage, the resistance that lies at the heart of this verse, right? That

Cuando el hambre me tire

el orgullo me levanta.

[that is: When hunger casts me down/pride lifts me up.]

Ahh, what a sentiment, right?

LS. Yeah, yeah.

CLIP #2 of Canción #2

INSERT #6

hern Veracruz. He was born in:He who has enough to eat

forgets about the one who doesn’t.

Remembering this Christian duty

isn’t convenient to the rich.

But I have a lot of power

in my poverty;

my pride sustains me through everything,

and many are amazed at how,

when hunger casts me down,

pride lifts me up.

___________________________________________

ELG. Tell me something…the importance of things like poetry, verse-making, music, dance. It’s that our whole interview has been in a context of social struggle, right? And the urgency, really strong right now, of changing our path forward as a society…it’s a constant theme at the Centro Cultural, I think. Because these arts, on the face of it, have nothing to do with social changes, economic change, changing economic systems, things like that. And many say, and have said over decades here in the United States, that these things, the arts, really don’t matter. I’d really like to hear your thinking about this question.

LS. Well…that’s an interesting question, because I think that for us, people who understand the value, not just of music and art, but also we who understand the value of caring for Nature, caring for the Earth on which we live, caring for the envirnment—it’s logical, it’s just common sense, that it would be a good idea to take care of your surroundings, because this is going to benefit not just you, but the person who’s next to you. It’s common sense. Sadly, in our modern world, it’s been abandoned. When we know that scientifically it’s been proven that a brain that has music and has access to unfolding itself through these media…

ELG. Mm-hmm.

LS. –well, it’s going to be happier, it’s going to have more ability in different areas.

Maybe—I don’t know if I’m going off on a tangent, but—

ELG. No! no, not at all! I think these media of communication that are music, poetry, movement, it’s exactly that they use other parts of this magnificent organ that we have inside our heads…[laughter] And so, I don’t know, we discover other pathways to change.

LS. That’s right. Just a minute ago you were mentioning the connection between the experiences of sadness and experiences of suffering, right?

ELG. Mm-hmm.

LS. And it made me think about, well, the experiences of Black folk, you know? People of African heritage in different parts of the world, having lived through centuries of enslavement, now today they represent one of the strongest and most important musical roots in the whole world.

ELG. The whole world, exactly.

LS. And [Black music] is still one of our main weapons for fighting back. I see it this way …I see it this way: as peoples, music is one of our weapons, one of the strongest tools we have, for communicating our experience to ourselves. And the people who can understand will understand, and those who can’t, well, they’ll miss it.

ELG. Well, yeah. but maybe sometimes, a rhythm or a movement or a phrase is going to catch their notice, and they’ll say, “Huhh…what’s that?” I want to leave open the possibility that sometimes music, song, can convince the buttheads. [laughter]

LS. Yeah…

ELG. –and sometimes maybe it can reach those who generally won’t listen to anyone!

I want to thank you so much, Luis. It’s always such a pleasure to speak with you, and I hope that we have many more opportunities in the coming years, and…we’ll be in touch!

LS. Okay, sounds good. Well, thanks to you too, for doing this. I got inspired, too. [laughs]

ELG. Ah, that’s great! That’s the best thing I could hear, so—you made my day!

OUTRO.

Luis is always overflowing with ideas and musical references; I couldn’t fit them all into our format! He recommended another group for their way of representing the voice and strength of a people: the Septeto santiagüero, from Santiago, Cuba, with whose catchy rhythms we close this interview.

CLIP of the SEPTETO SANTIAGUERO.