Shownotes

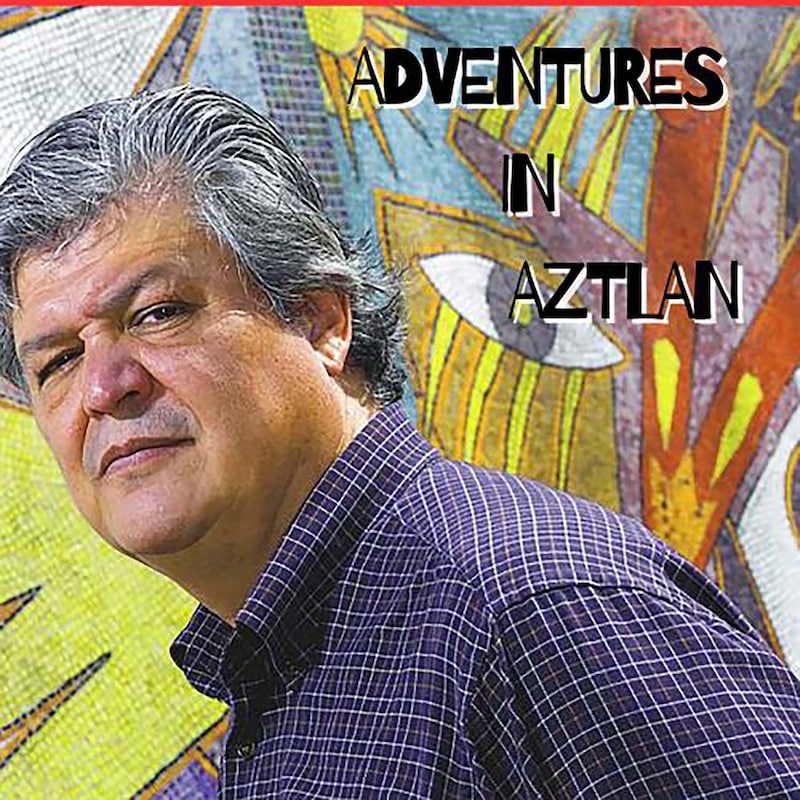

Born and raised in Mexico City Jose Antonio Aguirre has become internationally recognized for his venetian glass mosaic, and carved limestone murals many of which explore the people, places, and stories he has encountered as an artist who exists in two cultures bound by the Mexican and American bi-national spaces he has occupied for four decades.

The Journey of Jose Antonio Aguirre

In this episode of 'Change the Story, Change the World' we explore the life and works of Jose Antonio Aguirre, a Mexican-American artist renowned for his public art in the forms of murals and mosaics. Born in Mexico City and eventually making his way to the United States, Aguirre's multifaceted career spans roles as a muralist, teacher, journalist, and cultural ambassador. His work, deeply influenced by his bi-national experience, celebrates cultural heritage and challenges viewers to consider social issues and their own identities. Notably, Aguirre collaborated with significant cultural and community institutions such as Self Help Graphics and Art in East Los Angeles and participated in the creation of the Cesar Chavez Memorial. His journey underscores the power of art in community building, heritage preservation, and social commentary, all while navigating the complexities of his adventurous life in the U.S.

00:00 Welcome to Change the Story, Change the World

00:12 Journey to Knowledge: The Power of Public Art

01:30 Jose Antonio Aguirre: A Life in Art and Cultural Diplomacy

04:10 The Chicano Art Movement and Self Help Graphics

08:39 A Serendipitous Journey from Music to Muralism

20:57 From Chicago to California: A New Chapter in Art

31:49 The Evolution and Impact of the Mural Movement

41:10 Closing Thoughts: The Role of Art in Society

Bio

As a visual artist, I am dedicated to nurturing the development and production of an ongoing body of art that utilizes a variety of traditional mediums, materials, and techniques in combination with an experimental approach to contemporary technology and social issues. I seek to explore the application of space within an installation, painting, print or public environment that invites the interaction of the viewer with the elements of the composition; the spectator is to be engaged as an active participant and not a passive observer. The nature of my art is dependent upon the exploration and exportation of images, icons, symbols, and signs that have been contained within the continuity of creative expression in Mexican art from 3000 years ago until today. The essence of my iconography is traced from my personal pre-Columbian roots and it’s mixing with religious symbols of Spanish colonization, and compounded by the contradictory reality of “modernism” in Mexico and the United States. The content is inspired by the duality of history and social experience; the color palette inspired by the richness of the folk artists hand and the local regions natural landscapes. Reflecting upon my place of origin (Mexico) and its impact on the recent history of my experience in the United States, I probe the aesthetics of an artist that exists in two cultures bound by bi-national implications. I create a visual imagery that provokes definitions and questions that attempt to integrate the tentative everyday experience of human nature and its social implications with the cultural diversity of living on the border of two worlds that exist in the time of expanding globalization.

*******

Change the Story / Change the World is a podcast that chronicles the power of art and community transformation, providing a platform for activist artists to share their experiences and gain the skills and strategies they need to thrive as agents of social change.

Through compelling conversations with artist activists, artivists, and cultural organizers, the podcast explores how art and activism intersect to fuel cultural transformation and drive meaningful change. Guests discuss the challenges and triumphs of community arts, socially engaged art, and creative placemaking, offering insights into artist mentorship, building credibility, and communicating impact.

Episodes delve into the realities of artist isolation, burnout, and funding for artists, while celebrating the role of artists in residence and creative leadership in shaping a more just and inclusive world. Whether you’re an emerging or established artist for social justice, this podcast offers inspiration, practical advice, and a sense of solidarity in the journey toward art and social change.

Transcripts

Jose Antonio Aguirre

[:The mural, called A Journey to Knowledge which was commissioned by the Los Angeles Unified School District, serves as a both greeting to the community, and an invitation the attending high school students to, in the words of mural's creator,“ soar into their studies and life by being proud of their cultural heritage, to discover new paths and find themselves as they search for knowledge in their minds and souls.”

The muralists name is Jose Antonio Aguirre.

Given Jose Antonio’s extraordinary life’s journey as an artist, teacher, journalist, and cultural ambassador, this invitation is an apt description of his own open and adventurous approach to navigating the world around him.

Born and raised in Mexico City Jose Antonio, has become internationally recognized for his venetian glass mosaic, and carved limestone murals many of which explore the people, places, and stories he has encountered as an artist who exists in two cultures bound by the Mexican and American bi-national spaces he has occupied for four decades.

In this episode Jose Antonio takes us on the journey of exploration and adventure that began when he was a young man on a short visit to Chicago in search of a concert ticket and an electric guitar.

[:Jose Antonio Aguirre: I've been doing public art. for almost four decades, and at the same time, I've been involved in other things like being a cultural journalist, an educator, and also, an organizer and cultural ambassador,

BC: So how does cultural ambassador work show up in your journey?

[:And in a sense, I still do that because I’ve been volunteering as a Director of the Mexican Cultural Institute here in Los Angeles. And part of our mission and objective is to be able to cross the border, meaning that we go south, and we come north, make that communication and that connection with artists from both sides of the border.

[:[00:04:19] JAA: Well, Self Help Graphics actually is, celebrating 50 years of existence. It was founded in the early seventies, by a Franciscan nun, sister Karen Boccalero with two Mexican artists, Carlos Bueno and Antonio Ibanez in East Los Angeles. they decided just to, to start doing a little, a studio in her garage, and the kids will come around and check out.

And so, I started to give some lessons. And from there, they started expanding into doing some, artwork shops, for some of these, young people in, in some of the parts, and eventually they were able to get funding to establish the organization. Sister Karen was also an artist.

She was a, a printmaker, especially in serigraphs, silkscreen. And, at one point, they decided to approach that medium to start doing some art. just as announcements, to do an announcement for a gathering and, a talk of Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta, and they will be dancing or whatever, so they started doing this posters. flyers which at one point she decides to concentrate just doing art per se, taking all the lettering out and most of the time. And, and from there she started getting funding to invite artists and create what she called the Atelier. In which the artists will come, produce a print with a master printer, have that experience, it's right in, in, in Los Angeles.

Something that didn't happen, it was happening just in the west, side other shops, like Gemini, et cetera, you know.

BC: Gemini is one of the epicenters of the printmaking world working with mainstream artists like David Hockney, and Jasper Johns. Yeah.

yes, and she wanted to give that experience to the local artists. Which actually led into a very interesting situation because now. Most of those artists from that first generation, they are very well known artists in the community and on a national level, and internationally. it was very important,

[:It's where the community really found, a magnet for expression and activism.

[:Also, we have to take into consideration a lot of these artists didn't have the experience of other communities, especially in the west side of Los Angeles. They didn't really have access to galleries, or an art museum, So this was, the idea was to start bringing that experience right in the heart of the community.

And among them, culturally speaking, one of the most important things was to do Day of the Dead. .The Day of the Dead really established a very strong connection with the roots, the cultural roots, and also emphasizing the, the honor of the departed, loved ones, I mean, it brought that awareness that you keep them alive in a sense through memory.

And that was very important, for the community.

[:[00:08:39] JAA: You know, it was very interesting because I never believed I was an artist. When,… I mean, actually, it was an evaluation when I was in elementary school. A psychologist told my parents that, I was an artist. And I thought “An artist!” For us, artista in Mexico, at that time means the people who were doing movies, like Cantinflas.

I couldn't see myself doing that, and it took me really. quite some time to realize. Although I was inclined to do a lot of drawing it was actually a discovery. When I was, thinking how I will describe myself, I'll say, well, probably a discovery but I started as a musician in Mexico, and also that was by accident.

I was in high school, and my math teacher failed me in the last exam, which did not allow me to go to the University of Mexico, the campus. I wanted to be an architect. So, then I realized years later that it was a very lucky strike, because that's when I decided that I would like to go and study music. I had a rock and roll band.

Which actually also led into a very interesting situation because I, I remember one day I had this vision, with my friends we were jamming and, in this classroom, and suddenly I see this sort of like an angel, floating in the air, and he was touching all our heads. And that was a very fantastic vision because then I realized that we were blessed or touched by the angel of creativity, and and then we were visiting, family in my parents’ hometown in Cali, Scotia, Cal teaching.

And the cousin said, You're in vacations. Let me invite you to go to, Chicago. Let's travel to Chicago. I'm driving. just get your passport and for me, it was like, yeah, I want to see the blues and see, one of these bands that I, I liked so much, being a real concert. And, so, I traveled to Chicago I had as a goal to buy an electric guitar, see a rock and roll concert.

To me, it was an adventure. II had grown up in Mexico City and there was a writer Carlos Monsiváis, who labeled our generation as the first generations of gringos being born in Mexico. And the reason was, is because our TV was all these, programs, the Untouchables, Batman, Superman, and the music was the same thing. you know, Grateful Dead, the, Janis Joplin, Hendrix, obviously the Beatles, it was all this English, music, so we had this attraction. We admired the United States a lot So there I go, and, at one point, my cousins say, “Well, there is a job. Would you like to work?” And I say, “Yes,” because my problem the guitar. that I wanted was very expensive.

So, through that adventure of, going to Chicago, then I realized, “Okay, I'm going to stay six months and work.” Interestingly without, having any documentation, at that time.

[:[00:12:20] JAA: my father writes me another letter and says What about you stay for a year, study English, considering to go to school? I enrolled in American Conservatory of Music and Composition. We're talking 1977, and, then, I was having a lot of difficulty. Well, first of all, the language, and also realizing that a lot of my classmates, had studied since they were kids, and here I am trying to, to become a musician, in my twenties,

So, I'm going through that. I was very shy. You know, between classes, I will sit in the stairs and start sketching, or writing things. And this, student came to me and he says, “You know, what, I think you should be across the street.”And

I got offended. Immediately and I said, “What are you talking about?” And he says, “No, no, no, no, no, this is not to offend you. My friends and I, we will be looking at you every time that is between classes. Here you are sketching, and we like your sketches. But we can see how difficult music for you is.”

So, across the street is the top school in art, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Maybe you're in the wrong place? So, to make the story short, I visited the school, So, I go and get out and I'm looking for the restroom. And when I hear this very interesting sound coming, like “Tick, tick, tack, tack, tuk, tuk,” from a door. So, I peeked inside, and it was the sculpture department. they were, working with stone. They were doing clay. So, I started looking around, and I ended up exploring the whole school.

At that moment, I say, “Okay, something's happening here. A few days later the museum, It was free entrance, and it blew my mind. I was able to see all the impressionists, Lautrec, Van Gogh, and even going into modern art with Picasso.

Even they had Siqueiros and Orozco, the Mexican painters. And I remember looking at the water lilies of Monet, and that moment was a catharsis for me. That was the moment where I felt that something invaded me. And completely changed my, my life because I knew that that's the place where I wanted to be.

So, I told my mentor, the great writer and journalist, Luis Spota. And somehow, through his contacts, he made possible for me to get a scholarship from the Mexican government to study at the Art Institute of Chicago. So, I went back to school. I told my teachers that I was, leaving and I was going to enroll at the School of the Art Institute which I did.

And that's how I started doing art. Interestingly enough, when, when I was, enrolled in the School about, the same time, I learned about, Chicano, Muralists or Mexican American murals in Pilsen, which will be the Chicago. equivalent to East LA. And I there was a Spanish newspaper, and I went and asked the owner, because I was working as a waiter for this restaurant La Margarita. And the owner of the paper was the same person, Mr. Dobalina. So, I went and asked about how I can get in touch with those people and he says, “Well, go to Casa Aztlan, and, and talk to so and so. And that's how I started doing murals too.

[:[00:16:07] JAA: Yes, and actually, it is, it was very interesting because for me, growing up in Mexico City, I was surrounded by the muralists. And especially, I remember being really seduced by ones that made in mosaic, which I didn't know that years later that would be my main medium in public art, between mosaic and also, stone, limestone,

[:[00:17:04] JAA: I had the opportunity to meet this fantastic artist Felipe Ehrenberg. Felipe went to Chicago to do the first altar of Day of the Dead, which actually blew my mind because he was also doing it as a political statement. He was denouncing the situation in Central America at that time. So, then he comes back a year later, we're talking 83, 84, to be a guest artist for a semester doing a class in arts and politics I got into the class. as we call it oyente, (listener). I was just, crashing the class on his, with his, okay.

Felipe didn't call himself artist. He called himself a neologist, for a long time, he refused to use brushes, he would be using either wood or, metal. And he will be using the spray, and he will be using the stencil. And also he was considered, the grandfather of performance art in Mexico.

BC: In a:It is still told that it was the younger Lord

who had surrendered to the Iberians the

kingdom who surrendered his people's spirit

I am Felipe and this I was taught with the

voice of blue sadness’s of those who

lost but also with the red voice of the

exaltation of those who won

is that which we Mexicans say today

with sadness covering our joy.

JAA: And so, with Felipe, here we are, having this great connection, and he says to me, “I got invited to do a mural at the University of Illinois here in the Chicago campus. I want you to come over to this meeting.”

It was a Latino cultural center. But what I didn't like is that all the students that were there, everybody was like grabbing a little corner of that, space, and they were going to do their thing, So I say “Felipe, I'm not going to be part of this project.” He says, “Why? I said, “Because this is not the way I conceive murals.

I think you have to integrate the space, have a narrative, and everybody here is just going to paint a little thing and that's it,”

And he says, “You know what, Jose Antonio, here, two things. I want to give you my, my daughter.”

He had found this:I team up with, Raul Cristancho from Colombia and, Ran Stewart from, from England to, to really take care of this mural with the students. So that mural, entitled Nuestra Esencia, Nuestra Presencia “Our Essence, Our Presence “was finished In 1985. It represented important events in the history of Latin America prior and after 1492 and the subsequent Latino history in the United States.

BC: Ironically In late:[00:21:00] JAA: So after that, my mentor Don Luis Spota passes away. But I'm saving money and working. And unfortunately, the other thing that happened, it was the Mexican earthquake in September 19, 1985.

News Report

And that impacted my family. We lost our home. There was nothing in terms of, they're being hurt. So, I decided to give them all my money, to, to help them. And, and at that point I'm thinking, what am I going to do? And I just started thinking, well, probably I'll continue school here in the United States.

[:[00:21:19] JAA: And that’s,… I started, applying to all the schools. And among them, were the schools here in California. And CalArts is very positive and they say, come back for after a year of doing your work in your studio, you'll be more. more, focused to do your master's.

And in the meantime, I moved to Austin, Texas, I was invited by the Chicana poet, Sandra Cisneros, who had the scholarship and say, well, here is some space for you. It's big enough to share it. And, so I go and, and this is where I meet Sister Karen too,

BC: Yes. So, you went to the Art Institute of Chicago and CalArts. Anybody in this country that is aspiring to have an education in art making, would give their eye teeth to be at either of those places, let alone both of them. So that's, that's quite something. I am assuming mosaics were not something you spent a lot of time doing at either institution. How did those little squares of glass enter into your story?

[:And so when I come to, Los Angeles, I was looking for a job and one of my uncles Jesse Aguirre, he was the head chef of the steakhouse in Knott's Berry Farm. So, he says to me, “I'll get you a meeting. Maybe you can get a job.” So, I get an interview with Robert, Bobby Brooks, who one of the main architects, He says to me, “José Antonio, well, we don't have a position, but we are renovating this area called Fiesta Village. And We really like your murals. let's talk in a couple of months.”

So, finally, I, we meet, and they say, “Okay, here are the blueprints. This is what we want you to do. But, will you do it in Mosaic?” And say, “Sure, I can do it in Mosaic.” So, I go back, by then I was already a resident at Self Help Graphics. So, I go very excited to talk to Sister Karen and say, “I got a commission. Yeah, I'm going to do a mural.” Sister Karen, she says, “You're gonna do mosaic, you know how to do it? “I say, “No..” “So what are you gonna do? Well, I said, “Where are the yellow pages?” I’m going through mosaic, mosaic, mosaic, looking for the material and stuff.

And, and then I get into the Joseph Jung Studio and Joseph Jung had been a artist doing a lot of mosaic work during the fifties and sixties here in Southern California, so we're talking and he says, “Well, you cannot buy the material anymore. The only place you can get it is from Italy from Ravenna. But the problem is, is that. You have to place an order at that time of $10,000 minimum because all the Arabs, are buying the material for,…” And I'm like, “Oh my God, $10,000 just for the material.” “But we can sell you whatever I have left over some previous projects. My wife can take you to the studio and we'll sell you whatever you need from there.” And then I say, “Okay, and I have another question for you.” And he says, “Yes.”

“Do you know where I can learn to do this? ? He's like, “What? I don't believe you. You have a major commission from one of the parks in Southern California and you don't know how to do mosaics.” So then he asked me, “When you went to school, do you have any foundation?” I say, “Yeah, I just graduated from the Art Institute in Chicago. with a BFA and I'm going to do my, my, master's at CalArts.”

l the L. A. County libraries.:So, that's what I did. So, that was, how I learned to do mosaic,

[:[00:25:48] JAA: Well, that happened because when I, finished school, there was a classmate of mine. Daniel Veneziano, who was working for the Department of Cultural Affairs for the city of Los Angeles. And he, started sending me to these different places. as a teacher And I was in one that still exists, William Grant Still Art Center.

And, the receptionist, when she saw my work with the students, she said, “You know what, we have a colleague here that you should meet. You should meet Sheila Scott Wilkinson. She is running the program for Arts in Corrections through UCLA Extension.” And I'm like, “The prisons?” “Yeah, you would, you will be a fantastic teacher in the prison system.” And I'm like, “No way, I'm not going to go there. What are you talking about?’ But every time I went to do my job, she says, “Did you bring me your resume.”

So finally, one day I I'm going to just give it to her and forget about it. Right? Well, no, So I got a call. And I did my first stint at the women's prison. And it was interesting because they liked the mosaic idea.

And the second thing which really brought me into the picture was that, Bob Fraser was, the Facilitator at, CRC in Norco.

[:It's a very strange and interesting place. When I first went there to set up their Art in Corrections classes that Castle housed 500 or so incarcerated woman. We did a film there with the director Yurek Bogayevicz that was a retelling of Cinderella featuring with incarcerated women actors. Yes. Very strange. And I have to say that Bob Fraser did a great job as the Artist Facilitator.

[:So, I told to myself, “You know what, Jose Antonio, the only thing you know about prisons is what you read in the paper or what you see in the movies. Maybe this is the moment for you to really open the door and go and check it out and learn.”

And I have to tell you, at that moment, when I started doing those classes, it really blew my mind. It was very interesting to see, first of all, the great talent that was in there. So, I started doing other institutions like, the institution for men in Chino, Calipatria, and, the one in Blythe, Ironwood.

So, I started doing these things in different institutions until finally, Pablo Friedman from Calipatria said, “José Antonio, you should become a Facilitator.”

BC: Just to clarify for listeners. At that time An Artist Facilitator was a civil service artist who both taught and coordinated the multi-disciplinary arts programs in the California Prison system.

JAA: Pablo said, “This going to be some openings, you should apply for it.” And I'm like, “I'm not sure, Pablo.” he says,” Listen, you're very good, you're going to be, it's going to be a fantastic opportunity.”

And needless to say, I just had gotten married, and the first baby was coming in. So, he says, “And besides, this will be some stability for this year that you're starting a family”. And they did it and I went to Wasco. And I stayed in Wasco for seven years as Artist Facilitator.

[:[00:30:09] JAA: I got a call from, the art program at Metro, they wanted some mosaics for a project that Judy was making for a Metro station. So, I couldn't understand exactly. what they wanted, and I decided to call Judy. And when Judy learned that I was doing, the mosaic and stuff, “Well, I'm working at the At the Cesar Chavez Monument in San Jose State.”

It weas a fantastic project. So, I I become part of the team to do the mosaics. For the floor, there is a circle and eventually I got involved in doing the, the main, union workers eagle in glass, plus the main mosaic for, for, the portrait with, Cesar Chavez, and it was a fantastic experience.

memorial at its dedication in:[00:31:10] BC: There is an assumption I think, informing our conversation that murals have played a significant role in the social and political life of many communities, in Central and South America and in the US. Could you talk about the evolution of the mural movement and its role it has played in so many community stories.

[:As a matter of fact, I think the interesting thing between the, connection with Mexico and the United States and even in South America was that that rebirth of muralism, when Siqueiros and Rivera, decide to visit these different places in Italy to see that, that cultural legacy. And they took the philosophy of Dr. Atl, Gerardo Murillo, the painter, who had been advocating to do murals.

l character coming out of the:[00:32:00] JAA: Yes, and they come back to Mexico, and the interesting thing is they didn't know how to do those murals, how to paint them. So, they had to discover the technique. First of all, they were trying to do, encaustic. The first murals were in encaustic, which, they still exceed some of them at the old high school, San Ildefonso. And, and then they tried to use different elements like, Like the cactus juice to see it could be a binder.

Until finally there was a, a young guy whose father, he knew the old technique because they were doing that as a decoration in different houses, which is the fresco technique. So finally, he says, “Well, what you guys are trying to do is this technique that my dad uses and I've been helping him into.” So they rediscovered the lost formulas for fresco through this, young, young man who become, became also a muralist and they start applying it, through different projects.

Interestingly enough, Siqueiros never liked that, material. He was the one who was advocating to use the medium and the technology of the era. So, he started using the industrial paints, especially from the auto industry. and applying with, when he comes to, the United States and he discovers the airbrush, he connects with that.

So, You know, they bring the mural movement into South America. That's when they approach it more into the historical and educational part, and again, talking about the social issues that were in some areas.

And somehow that spirit is captured. in the United States, with the WPA works, when you see some of those murals in some of the old, post offices of some of the schools, the ones that survive, you can see that was the idea, the education of, what has happened, I think, in the last, 20 years or more, is that in Mexico, suddenly was out of fashion because of the fact that the, the aesthetic inclination was to be universal. And that's when actually a lot of the conceptual art and a lot of abstraction took place in the movement in Mexico. And, it got kind of, it got back with the street art or urban art.

But one of the differences that I can see is, that the system the institutions are trying to, to hold you back. I mean, you have to, to present a project to be approved. And what I have seen lately in most of the murals, especially in the United States, and I might be wrong, but because I don't have full, full knowledge, is that it's, a lot of them are a decoration.

With the issue of, during the pandemic with, with, George Floyd, the abuse that he suffered in Minneapolis. There were some murals talking about, those issues of injustice. But in general, I can tell you that I think that the mural movement right now has lost its teeth. a garra. I would say, is not really bringing the kind of awareness that is needed to make things change.

The other part is with the murals is that the painted murals, especially in an exterior setting, is they are prone after a few, some years to, start disappearing, So you have wonderful work that vanishes, I mean, probably is very well documented, but it still vanishes. the reason why I got attracted to mosaic was because, also, all the murals I painted in Chicago had disappeared, or were disappearing.

That's part of the attraction that I have for public art. Using the mediums that I use, is the idea that, first of all, there is an art that belongs to everybody. This is not something that belongs to a collector, it's not in a gallery, or it's not in a museum. Not that that is wrong with that, but, most museums, if you don't pay you won't be able to see the art, but in here, you have an art that is accessible to everybody, and that also, you know, somebody can tell me, “Well, that person doesn't care for that.”

I say, “Well, maybe they don't. But if this is the route to this metro station, they will be exposed.” At one point you're waiting for the train or you're just walking by, but it's going to catch your eye and then maybe it's going to create question and it's going to make you think,

But right now, I will tell you that I think that the mural movement in, most of it is not about sending a message, trying to change things, trying to bring awareness. It's mostly about being cute, beautiful,

[:[00:38:17] JAA: a decoration.

I remember my, great friend and mentor Felipe Edinburgh, we were talking about the new collectors in Mexico, this, younger, very professional guys, you know, Felipe get invited to one of the most exclusive areas in Mexico to this dinner and the guy, the owner was like bragging about his painting.

And he's looking at the painting and the painting practically is, like just this splash of paint. And Felipe, he's asking him about why he really likes that paint, to the collector. And he says, “Well, it's because it cost me $50,000 in New York. It's, I mean, “That's what you like it for?”

“Oh, well, and it has a red that goes with, my wife's, choose, choosing that living room.” You know I mean, it's like, what are we talking about? What are we talking about?

[:[00:39:11] JAA: Exactly and actually You know the less information you have the less you think. The advantage is, you know, for whoever wants to be controlling us.

[:[00:39:39] JAA: I think we still have to be stubborn in that sense, I mean, it's portraying our current reality. Somehow that has to be said, established. And the problem we have with public art in that sense, It's that it's controlled either by these budgets that belong either to government agencies or private, developers that, like I say, they have the last word to say, we like this or we don't like this.

And, and most of the time, what I can see is that unless you have agencies that are really visionary, that will give you the room just to express yourself, it's been dictated. I've been saying that I think we are in a time where, for example, the public art programs have to be reevaluated and restructured.

You have all these people to be in a selection committee, and sometimes I don't think they have the understanding of the value, the historical value, to leave a mark, to make a statement of our times us, even not just to challenge what is going on, but also to leave a sample or something for future generations to say, this is what's happening, this is what we went through. And, things were solved or not solved, but hopefully they will bring certain attitudes that will push, again, the non-artists to think about it and take a stand for whatever the issue is.

This seems like a good place to close. Thank you so much Jose Antonio for sharing your stories

[:[00:44:46] BC: And to our listeners. Thank you for the time that you've spent with us here. And if you want to jump in on the ongoing conversation we are having here on this show or have suggestions for guests drop us a line at csac@ artandcommunity.com. Art and community is all one word, and all spelled out.

Change the Story, Change the world is a production of the Center for the Study of Art and Community, our theme and soundscapes spring forth from the head heart and hands of the Maestro. Judy Munsen, our text editing is by Andre Nnebe, our effects come from free sound.org and our inspiration comes. From the ever-present spirit of UKE, 235.

So, until next time stay well, do good and spread the good word. And once again, please know that this episode has been 100% human.