Shownotes

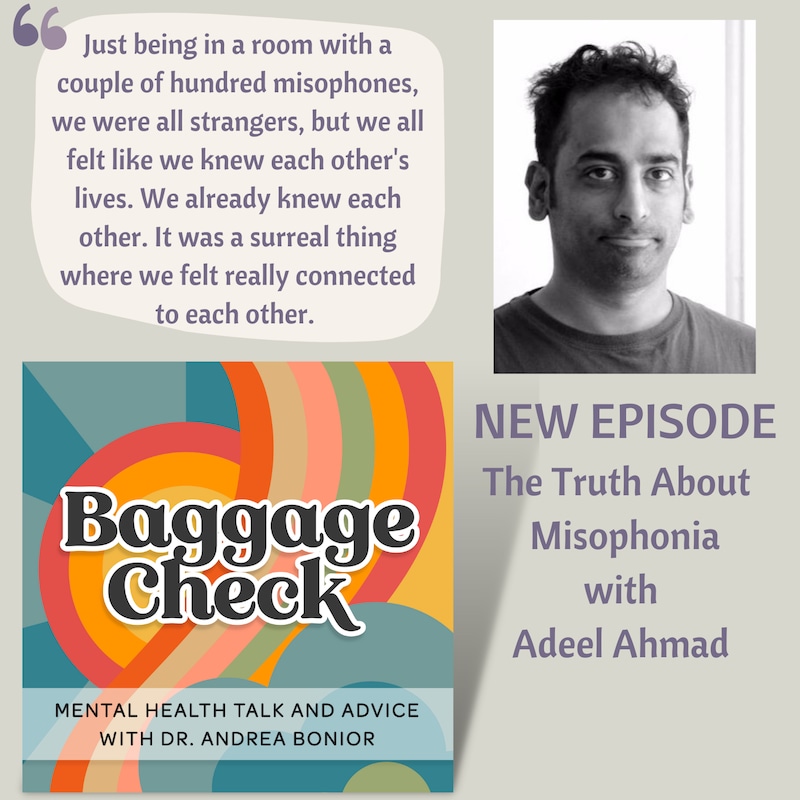

Today we're welcoming podcast host Adeel Ahmad to talk about misophonia-- which can be misery for those who suffer from it, and yet they may not even know that it's a "thing." Misophonia involves being hypersensitive to certain types of sounds, commonly noises like slurps, chewing, and crunching-- and it can wreak havoc on families, emotional health, and relationships. But there is hope!

Join us for a remarkable discussion about Adeel's own story of misophonia, the way he's brought sufferers together, the surprising childhood factors that may contribute to it, and how people can have hope to ease their suffering. From thinking about evolution to childhood drama, we go deep-- with empathy and compassion, and absolutely no crunching sounds-- we promise.

Check out Adeel's podcast, The Misophonia Podcast, with stories of people from all walks of life who are living with misophonia.

Follow Baggage Check on Instagram @baggagecheckpodcast and get sneak peeks of upcoming episodes, give your take on guests and show topics, gawk at the very good boy Buster the Dog, and send us your questions!

Here's more on Dr. Andrea Bonior and her book Detox Your Thoughts.

Here's more on this podcast, which somehow you already found (thank you!)

Credits: Beautiful cover art by Danielle Merity, exquisitely lounge-y original music by Jordan Cooper

Transcripts

Dr. Andrea Bonior: If I were to start chewing really loudly into this microphone, would you want to haul off and hit me? I mean, seriously, would it be one of the worst things I could possibly do? Do you know someone who is so triggered by certain sounds that it started to cause conflict in their relationships with others? Today we're talking about misophonia, an oversensitive reaction to certain sounds that can make listening to things like chewing or crunching excruciating. We're welcoming Adeel Ahmad, the host of the misophonia podcast, to talk about life with the realities of it, the very surprising things we know that might contribute to it, and how to find some hope and compassion. If you've ever wondered why certain sounds bother you even more than the proverbial nails on a chalkboard, you'll want to listen to today's Baggage Check.

Welcome. It's really good to have you here. I'm Dr. Andrea Bonior, and this is Baggage Check: Mental Health Talk and Advice, with new episodes every Tuesday and Friday. Baggage Check is not a show about luggage or travel. Incidentally, it's also not a show about how there are a lot of people using the word bespoke without actually being able to define what it means. I'm not really sure either.

Okay, on to the show. Today we're talking about misophonia, a condition that has gotten more attention as of late. Talk show host Kelly Ripa has spoken out about having it. There have been some high profile pieces about it. It's a hypersensitivity in a negative way to certain sounds, often things like mouth sounds, chewing, crunching, slurping. But it could be any number of sounds. And it's one of those disorders that you might not know there's a name for, even if you're experiencing it. And it may wreak havoc on families and relationships before you even realize what's going on. But not only is there a name for it, there is hope. So I invited Adeel Ahmad to the show. He is the host of The Misophonia Podcast. That's the title of the show capital letters, the Misophonia podcast. And it's wonderful. It's welcomed all kinds of people from all walks of life who have this challenge. We had a remarkable conversation about his own experience of misophonia, how it impacted his relationships and his parenting and his family, and how he's connected with other misophonia sufferers in a big way. He brought up some fascinating theories about the science behind it that, honestly, we're pretty startling to hear in terms of what might be going on in the brain. There is so much good stuff here, and I can't wait for you to listen. So let's get it started.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: I am so happy to have you here today. Welcome to Baggage Check.

Adeel Ahmad: Oh, it's great to be here. Thank you, Andrea.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yeah. So I just heard of misophonia. I guess it's been many years now, but when I heard about it, it was kind of a revelation in the sense that I'd been in the mental health field for a while, and I considered myself relatively knowledgeable of various sort of rare quirks of the brain. And this really was something of a revelation because I think when I first heard about it and I started to hear people's stories, it really made sense in such a way that this is something that affects people's lives really deeply. Because it must be very hard to get away from. If this is so I'm so glad to be able to talk with you because I think this affects a lot of people. And maybe they don't have a name for it, and maybe they feel like there's something wrong with them that's deeper than this. Or they feel like an outcast, or they feel like they're mean. Can you talk about your own story and how you came to discover this about yourself?

d two thousands, and then the:Dr. Andrea Bonior: It's so powerful, that notion of being able to connect with people who had similar experiences that maybe at the time they thought were theirs alone, and they felt maybe like an outsider, they felt something was wrong with them. I think that's something that I see all the time for various challenges that people face, whether they be something widespread, like depression, where people maybe know that it's a thing, but they still feel so alone, or something more rare like this, where it's like, I didn't even know there were other people that felt this way. And you refer to some of these second order types of ripple effects and I think that's so fascinating because this isn't really just about how you maybe process sounds and how you react to that, but it's also about relationships, it's about interactions. I wonder if you could say more sort of first about how we might define misophonia itself. But then also too, I'd love to hear more about the nitty gritty of how it affected your friendships, how it felt to be a teenager who felt like maybe they were just more grumpy than everyone else.

Adeel Ahmad: That's a good point. I didn't define it. Uh, you probably did in the intro. But I actually don't even define it on the podcast because uh, it's I guess targeted for people who have misophonia and to talk about, to do real talk. Um, and we just kind of get into it. But yeah, I mean misophonia is and I don't know if this is honestly an official definition, but I just describe it as a disorder that's an irrational reaction to certain, usually certain sounds. Not just every sound, not just loud sounds that's hyperacuous. But it's usually very specific sounds. They're usually sounds that are mouth related. But there have been a number of other types of sounds. Like uh, somebody said the sounds of um, skin movement because uh, growing up her dad would clap his hands together and rub him really hard together in the morning to warm up. Sometimes it's not in the same mouth sounds or crinkling or gum chewing uh, these are very typical kind of sounds that trigger people. Now their reactions tend to be a lot of people might be annoyed by certain sounds, uh, but it's very much a fight or flight, uh, or feign reaction where we're hyper focused on the sound. We wish we would not be hyper focused, uh, to the sound. This gets to. Uh, another thing. We're always told that uh, why don't you just tune it out once you snap out of it? It's not possible to do that in most situations. And so there's this fight or flight situation where we need to get away. Or we feel like honestly, we have sometimes quite sickening, violent thoughts of what we want to do to get rid of that sound. No one ever acts out on it, but it's that intense. Um, and we can't focus on anything else. So that's what we're talking about here. And so when someone, maybe somebody is causing that sound, it tends to build up all of this baggage or uh, it assigns all these attributes to the person making the sound, which we don't want to have to assign like this person is doing on purpose, this person is trying to hurt me. Um, we feel very much unsafe. Mhm, and it's like uh, kind of a lizard, um, lizard brain reaction. And we can talk about some of my thoughts on where this all comes from. But, yeah, it's a very raw reaction. It's not like we've thought about it, and we're like, oh, yes, I find that sound very annoying and I must run away. It's immediate and, uh, it's very intense. So, yeah, that's a little bit about kind of that initial reaction.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Um, yeah, and it feels very much it sounds like that real nervous system reaction of threat. Right? That sympathetic nervous system says, hey, we're fighting, we're fleeing, maybe we're paralyzed with fear. I mean, just in the same way that somebody with a snake phobia might go into absolute panic mode, even though people have told them a hundred times, hey, that snake is in a case, and, um, this is a reptile exhibit and he's not coming out of the thing. They feel like they're under threat. And it sounds very similar in that way. Like, you don't want to be upset by that sound, but something almost prehistoric is activated in your nervous system that says, oh, this is a threat, this is bothersome. And it sounds like sometimes it's even easy to feel rage for a person that you don't want to feel rage. That must be so disheartening to not want to feel that way. I don't want to be mad at this person. I know they're not doing it on purpose, and yet here is every fiber of my being saying this is the worst thing that they could possibly be doing right now.

Adeel Ahmad: Uh, it's funny, I describe it as kind of it's like Jekyll and Hide. We'll switch from, like, totally chill to total rage, but it's not just Jekyll and Hyde separately. It's almost Jekyll Hyde at the same time in your head, because your rational mind realizes that this is not an unsafe environment. You're okay, you shouldn't be mad at this. But this I think Hide is the bad guy. But, um, that side has taken over. And so it's an internal struggle, and it's exhausting. Like, we are exhausted after this. Uh, and on top of that, once we get out of the exhaustion, we're left with, um, this weird resentment and anger, which we realize should not be there. Um, but it's very much and we can get into kind of like, ideas, uh, on where it might come from. But it feels like as I've learned more about it, it feels like some of this comes from maybe situations growing up. And I've talked to a lot of folks, obviously, on the podcast, most people have had some kind of walking on eggshells kind of childhood situation where either there was a lot of chaos or there was, um, kind of a low level chronic trauma. Maybe an angry parent, an alcoholic or something like that. This is a very, very common trait or background that a lot of us share. I feel like, um, no doctor or researcher, but I feel like there was ah, that child brain assigned learned that certain sounds were a warning that something might happen and that did not, um, leave as you grew up. And so suddenly now sounds that your child brain assigned to imminent danger that doesn't need to be there, but it's still there.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Right. That's fascinating. Sort of like that hypersensitivity to threat that we see in some people. Prone to anxiety, high levels of anxiety. It's like that false alarm because I've been primed to think that something's going to be happening that's terrible if this trigger happens. It's also interesting too, the idea that maybe something's going on environmentally in a lot of these kids homes. One thing that comes to mind as somebody who consumes a lot of research and thinking, part of me is like, I wonder if some of these parents had undiagnosed misophonia, which made them more prone to be angry, to struggle with alcoholism, to create sort of an explosive, unstable environment. Do you think there's anything to that possibility? It'd be fascinating to do some longitudinal studies on this.

Adeel Ahmad: Absolutely. That should definitely be a, uh, point of research because uh, a lot of people who come on and um, obviously are not looking at the research, they're not doctors. A lot of people come on and say, I'm convinced this is genetic because I've had, uh, a parent who has had it, maybe, and also a grandparent, uh, or some other family member. But I think you're right, it's more likely that probably that there was some other, uh, Misophonia or some, uh, other undiagnosed, uh, or diagnosed issues that perpetuated mental health issues. And maybe in one generation it ended up being misophonia. Where the brain decided that, uh, warning your body, your nervous system of a sound is something that's worth doing and it just became stuck. But, yeah, it seems like I would not be surprised that, uh, that is the case, because I have definitely talked to quite a few people who said that thinking back, and sometimes they realize that on the podcast, it's not something that, um, they're thinking about as we're talking about it, uh, together, because no one has ever talked to them about it. Um, it seems like people will come on and say, yeah, I think my dad or mom was alcoholic, but it was also Mr. Funny because they would go crazy when we would be in the car doing this or that. Um, right. M. Yeah, there's m more to this than a single person in a family being, um, annoyed by sound, for sure.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: And I think so many mental health challenges are like that. There's something even below it. It's like, okay, this person is struggling with substance abuse, but really it's about trauma. Or this person seems like they're really anxious, but deep down it's about depression. There's so many times, and that's the privilege and the responsibility of the mental health professional. Often we're in that situation where we have to look below the surface. Sometimes in terms of what happened.

Adeel Ahmad: And that's kind of one of the revelations. I've only been doing this for three years. One of the revelations I've only learned about, I've realized, I think, recently, is that, uh, looking at misophonia not so much as, like, a defect, more of it's a, um it maybe now, or it was, at one point, a warning to something. It was warning you or trying to protect you from something, which I think is, uh I don't know. For me, it just seemed not just fascinating, but it's kind of a beautiful thought that, um, it was actually a feature, not a bug ah kind of thing.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yes.

Adeel Ahmad: Obviously, something went on. Maybe it's not needed anymore, and that's maybe more tragic, that something that was meant to help you is hurting so many other parts of your life.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: That reminds me just a lot of panic symptomology in that natural fight or flight response evolutionarily. It kept us alive, right? It allowed us to run faster. It allowed us to focus all of our energy on fighting that predator. And then over time in modern life, it's like, I don't want to have these same symptoms when I'm about to give a speech. I'm sitting in a fluorescently lit office, and I'm just trying to give a speech, and yet my body thinks I'm about to fight a cave bear or something like that. It is a feature, not a bug. It was developed in us for a reason, but now it doesn't serve our purposes anymore. It's so interesting, that connection, that maybe, in a way, misophonia, uh, is similar, maybe thousands of years ago, hey, if I hear these certain type of sounds, it means that an animal is munching on something nearby, and I need to be aware and hyper triggered by that. But now it's just my sister eating popcorn in a movie.

Adeel Ahmad: Right? Yeah. It's something, as you were saying, that, ironically, a lot of people think, uh, who don't have misophonia think, oh, it's just something that people are noticing now because of used, uh, to being earbuds or whatever. And it's just more of a modern phenomenon where it's kind of maybe, uh, a mismatch between what we needed back then and what we need now.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yeah, it's true. So, for you, what did some of those friendship effects look like? You mentioned the phrase middle school, and right off the bat, it's like, oh, middle school. That can be hard enough without feeling like, uh, oh, I have these reactions, and I get so grumpy, or I get so irritated, and I don't really know why, but I feel guilty about it. Can you talk to that?

Adeel Ahmad: Yeah. So, for me, in middle school, in school itself, um, I don't really remember being triggered so much in the school environment. At least, I don't remember any particular incidents, obviously. Like, I don't remember much day to day what happened in school, but a lot of people are getting accommodations now in in schools. But a lot of people were not so triggered in schools. It was more what was happening more at home around that time, like you mentioned. Yeah, because I think at school there's enough, like, background noise and chaos. Obviously not during exams. I do remember college exams, like being in giant gymnasiums. I could hear everything. And if somebody had a cough, I don't necessarily think it maybe hopefully not affect so much my results or anything, but, um, in a middle school environment, there's a lot of background noise and stuff. It, uh, was more at home when it was like sitting down for dinner or just uh, doing kind of quiet kind of family stuff, or sitting or being in a car where it was, um, definitely more of an issue. What happens is it's part of what creates that wedge between you and your family members, um, especially between your parents. And that's kind of what it's almost a universal phenomenon that happens. And, uh, you tend to because you don't know what it is. You don't know what the term is. You just assume that, hey, it's part of like the hormones things. And you're being a teenager, some teenagers rebel in some ways. And for me, maybe, uh, I just was annoyed by certain sounds. And that was kind of, um, one of the many reasons why I just kind of wanted to be my own person or whatever.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Right.

Adeel Ahmad: Or I was also very much into music, and maybe I was thinking, hey, I'm just very sensitive to sounds in general because, uh, I'm listening to a lot of music, and if something sounds weird, I'm put off by it. So these are, I think, kind of things that I maybe tell myself and we tell ourselves, but, um not realizing that, uh, it's something much deeper about these specific sounds.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Right. Is the sensitivity always in a negative way? I mean, obviously with the concept of misophonia would be do you feel like, in general, there are certain sounds that might be maybe even more soothing to you precisely because they don't have the grading qualities? Do you appreciate music more? Are there certain types of sounds that really you notice more because they are more calming? I mean, what's your relationship to sound in general?

Adeel Ahmad: Yeah, I don't know if there's certain sounds that, hey, I need to turn that sound on because that's, uh, a positive sound. Although I think there is some research going in that direction to maybe try to identify particularly positive sounds in people. Like there's a negative sounds, but maybe try to cancel out the effects of the negative sounds by maybe layering on certain positive sounds potentially in real time in the future.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Wow. So sort of like brown noise or white noise or that kind of stuff.

Adeel Ahmad: Maybe brown, maybe I don't know, a certain sound of a bird or something. Maybe actually a tangible sound that could kind of be layered on top of a trigger as it's happening. I know that I think there is some research, uh, going on in that direction, but for me, yeah, I don't think there's any specific, um, sounds, uh, other than when I'm being triggered or I'm in an environment where I know I'm going to be triggered by a lot of sounds. Um, I'll just throw music that I like on it's. Not necessarily, um, any kind of particular sounds, uh, in particular. But yeah, brown Noise is great. So white Noise for listeners, white Noise is kind of like the catch all term, but it's quite grading. It's all frequencies. Brown Noise is basically the highest frequencies taken, um, out. And so, yeah, in a pinch, that definitely works. And I actually layer that in the background of my podcast. After I've edited everything out, I put a little bit of background Brown Noise just to cover those little bits of mouth sounds that I may have missed in editing. But also if people listen to the podcast and they happen to be on a subway, it just kind of gives them a built in Brown Noise as well. Um, yeah, I wouldn't say there's any particular types of sounds that are maybe more soothing, but just the music I like to listen to and kind of Brown Noise in general. Um, there's amazing stuff on YouTube. Background noise.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yeah. Well, I love how you're creating a podcast. You're creating really a space to be welcoming to people with miscellonia that is safe for them. And you're going through that with such kindness and care. I'm sure your listeners appreciate that more than anything that your show is going to be a balm rather than being further agitating. Yeah, Brown Noise and all of the questions about frequencies and the emotional effects that they can have on us. It's so fascinating. I know there's recent research just about ADHD and Brown Noise and how Brown Noise might be helpful, um, toward people that have ADHD in terms of concentration. I think we have so much to learn about all of these things. And I know you're not a researcher, but how common is this? Do we have a sense of how common it is versus maybe we are only scratching the surface because a lot of people really don't know that this is a thing.

Adeel Ahmad: Yeah, that's a good question. Uh, I've heard numbers anywhere from like two to 20%. And I feel like the 20% is probably 20% of people are at least somewhat sensitive to sounds. But it could very much be, um, being sensitive to certain sounds in very isolated situations, but not in general. I'm not sure what the number would be for the people come on at my podcast. I don't know what the upper limit there is for the people who are very much like, I need to run as far away as I can immediately, or I need to smother that person with a pillow right now. Um, uh, I don't know what those numbers, uh, are actually. Um, I should maybe think about that more carefully.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Uh, well, I wonder, it sounds like maybe it's a spectrum too, right? Like most things in life that there are going to be people for whom this is so severe and it's impairing in their daily life and it's so distressing. And then there's going to be other people a little bit. Less than that. And then there's going to be other people a little bit less than that, and then you're going to get, at some point, to people who are more typical who yeah, even a typical person in if their uncle is chewing with his mouth still next to them at Thanksgiving. They might be slightly annoyed, but it's nowhere near the same reaction. Uh, do you feel like maybe misophonia is a more qualitative type of thing where if you've got it, there's something fundamentally different happening in your brain? Or do you feel like more it's sort of quantitative, as in, it's like just this more heightened extreme reaction that maybe everybody has a tiny bit of, but you just have this reaction in really huge ways?

Adeel Ahmad: Yeah, that's a good question. First of all, I don't think it's something that you're just born with mesophonic and um, I feel like if anything, there's a little bit, something a bit epigenetic where maybe you're more predisposed to then uh, maybe more predisposed to using while m you're growing up to have used sound as a warning to something. Um, I don't think it's just like, uh, everyone's sensitive, everyone has misapplied to some level and then some have it more than the other without any other inciting, um, factor. I feel like it smells like at uh, least to me, that, um, something is causing it growing up or somewhere in your past and it's that part of your genotypeptop phenotype, uh, whatever you want to call it, is activated or turned on. Um, I don't think it's just a spectrum that everyone's on and then we just happen to have more of randomly. But I also don't think it's just, ah, some brain disorder. I don't think it's like some wiring that you were born with without any other, um, factor. So there's something you're probably more predisposed to maybe part of your, part of growing up. Um, but I think part of epigenetics is like you were saying earlier, you're, um, a parent. Um, it could be passed on through generations by, um, I don't know how it affects the DNA, but, uh, it gets passed on and then it could get triggered, it could get turned on later if the conditions are right. And I feel like it's more that where it's a little bit messier as to what is causing it. Um, but it's not totally quantitative, right?

Dr. Andrea Bonior: And we see that in so much research about other disorders too. My students. Hear me talk about epigenetics all the time and that we're really seeing fascinating things. And essentially what happens is new layers of protein are added to the genes and so traumatic experiences or your ancestors living through a famine or something can actually cause those changes in the genes that are passed down. And then what eventually happens is in the womb. The womb environment can also determine what genes are going to be turned on and off. So identical twins might be as alike as two people could genetically be. But if one of them had a slightly different position and got more nutrients in this way or was exposed a little bit more to hormones in this way, you could have a situation where even at first certain genes in the one twin have been turned off in such a way where they haven't been in the other. And there's so much to learn. And obviously I am not a geneticist, hey, it would be great to have one on at some point. But, um, I think that's so fascinating because really there is no nature versus nurture, right? I mean, virtually anything is kind of that combination of that genetic predisposition and then depending on the environmental influences, that can be turned on because we really can't have genes expressed without an environment and we really can't have the environment acting on anything except what's already in your genes. So it's this constant cycle and it's fascinating. And hopefully it can also provide some hope that nothing is black or white in this. That maybe, for instance, if some environmental changes can be made that can help mitigate things or that can maybe prevent like if a parent knows that they have misophonia, maybe certain things that they can do to make their home environment more calm for their children or make sure that their children's anxiety is kept in check and that they feel more safe. Maybe that can help prevent a little bit the idea.

Adeel Ahmad: Yeah. And that's something that comes up in the convention this is a lot, is like how do we tell our children about this or do we tell our children about this? Um, this is nothing more than just a bunch of us hanging around a, ah, conference table in the middle of the convention. But, um, we usually come to the conclusion that we don't necessarily need to completely hide it, but we don't necessarily need to shine a spotlight on the misapply app. Right.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: It doesn't have to define you.

Adeel Ahmad: Yeah. And we don't say, hey everyone, I have misophonia, so everybody stopped. I need this to happen. I need that to happen. As much as we would like to maybe say that. But, um, I'll explain maybe what it is if it's asked. But I don't necessarily have to make it like you said yeah, part of my identity that then my child I don't want my child to then be worried about triggering me for sounds. And something that I've noticed since doing the podcast honestly is like, I will try extra hard now not to be triggered if my child is around and I'm being triggered now. Luckily, I've found, and most folks have found that our own children don't really trigger us so much.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Especially we normal parents are triggered by our kids noises.

Adeel Ahmad: Right. That's interesting irony there. But that just got me thinking to the whole maybe it's because um, my brain has told me, okay, your child is not the threat. You need to be protecting your child, not protecting yourself from the child. And so maybe that's part of it.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Uh, that's so fascinating and just uh, the way that you're able to see these themes because you're meeting, because you're having conferences, because you're having people on your shows, it's anecdotal evidence, sure, but it's meaningful patterns of data in its own right. You see these themes emerge and that's fascinating stuff. And I know it's kind of joking about it, that parents without Misophonia are often like, oh my goodness, my house is so loud and if my kid plays that toy one more time, I'm going to scream. So I think it's particularly striking that parents with misophonia aren't particularly triggered by their kids because it seems like there'd be such ample time. I mean, kids not knowing how to chew with their mouth clothes, kids slurping milkshakes in the backseat or whatever.

Adeel Ahmad: Yeah, I know that's interesting when you say that toy repeating over and over. I'll definitely notice that too. But I particularly I'm m not going to cause a scene. I don't want to be like 20 years from now and my child has missed a phone number and they could trace it back to when their dad was just kind of freaking out at every sound. Um, so maybe that's one little positive thing that if it can kind of like calm you down, but can you.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Say more about that? About maybe ways that you do attempt to be less triggered? Are there things that are helpful, things that are not so helpful for you to say, hey, I really want to make an effort here to not be as triggered in the situation. Obviously, you can't probably eradicate it completely, but are there tools that you use personally that are helpful for you?

Adeel Ahmad: We can get into some of the coping methods. I mean, I think we're uh, just working on the baseline of uh, and I don't do this particularly well, but just keeping the baseline of like sleeping well. If you wake up with completely sleep deprived, you are basically starting to set up yourself for failure for a lot of different things. Um, but then, uh, misophonia is definitely one where you could definitely, um, be triggered more. Just general stress level. If you're not having the greatest day, it seems like misophonia is two X, three X worse. You're more likely to get triggered. It's not just being triggered. The timeline of a misophonic trigger, uh, is the trigger, but then it's also the recovery time after it's like, how quickly can you get back to thinking about normal things? Because anyone who's got misfunction will tell you one little sound and you could potentially be thinking about that for hours, uh, afterwards. M, and it could completely throw off your day and your week. Um, basic things like, yeah, sleep and stress level, but having okay, so, um, I've got my AirPod Pros that are noise canceling. Having something within reach around without necessarily having to grab them and put them on is helpful because it tells your nervous system that you have, uh, an escape patch. You have something that could help you. Um, and then, uh, obviously if you need to put them in, you can put them in. But it's something that, uh, I was just texting with somebody earlier. It's something that, um, some people worry about. You don't want to be too dependent on constantly wearing noise counseling headphones because if you then go out into the world, you can become maybe extra sensitive to certain sounds because you're not used to them. Um, but yeah, noise counseling headphones are helpful, um, in a pinch. Well, okay, let's talk about more practical things other than sticking your fingers in your ears and everything, let's say. In a family environment, I don't necessarily have to sit down to eat all the time. I know people who, um, sit down to eat, but maybe you finish a little bit earlier to help with the dishes or something. Or you kind of like, float around the room where you're kind of around part of the conversation. But you're not necessarily like, sitting there in a quiet room. You don't have to be in a quiet room. You could be listening. You could have, uh, eaten your diner. You could have Alexa going on, um, playing some music in the background or having some TV. But these are some cupping mechanisms. If you have something in the background that could maybe mask some of the little sounds, uh, that is helpful humor, by the way. If you could talk to somebody, if you can talk to your family members and let them know that you have this, if anyone's going to be helpful, hopefully it would be your family members. They don't have to necessarily get everything right. But, uh, we find that if you get the sense that people are at least trying, that can really tell your body that you're in a safe space. Another thing I do is if I'm going to a situation and I don't necessarily have the tools, if I just tell my brain in advance, hey, you're going to sit down for a meal for about, whatever, half an hour or something, time box, it's going to be over in a little bit. You're okay. No one's going to jump on you, attack you. You're in a safe environment. If you kind of tell yourself that in advance, that can help. And then I'll say one other thing, maybe going back to the idea of that inner child that was scared a long time ago, if you tell yourself, thank you for warning me of these dangers, I love you, a number of people come on and told me that that is part of their therapy, their coping strategy. And I find that helps a lot too, to kind of tell your inner child that maybe is still wounded. Uh huh. Obviously, you still probably have maybe that speaks to maybe more work that you need to do on yourself. But if in the moment, I find that that actually helps as well, is to kind of, like, reassure that Mr. Hyde, that is kind of the grown up version of that child who was scared a long time ago. Now, this is getting into maybe deeper coping methods that, uh, maybe you didn't want to maybe one or more practical ones. But I find that that has kind of helped as well. And that's come up in conversations recently.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Well, I love that because it does speak really to the power of the emotional aspect of this, which is I am inherently unsafe in these moments. I'm inherently scared and vulnerable and angry that I'm unsafe. And I think the self compassion seems so crucial because instead of turning against yourself like, uh, oh my goodness, I hate this about myself, I wish I didn't have to go through this. You're saying, look, there's a part of this that served the purpose, there's a part of this that came from maybe some tough environments in the past. It's trying it's trying to help me. It's trying to warn me. It's trying to do the right thing, just like that fight or flight syndrome when I'm trying to give a speech. I hate the fact that I have butterflies in my stomach or that now I've got armpit skins from my sweat. But there's some part of me that was trying to be helpful to my evolutionary preparedness or whatever. And I love the self compassion we see that go so far for so many different psychological challenges. The notion that you can calm and pause and thank whatever's happening, even if you don't want it to be happening, but you can appreciate the fact that it's there maybe for a reason.

Adeel Ahmad: Yeah. It does not point to the idea that, uh, it was meant to help you at some point. Something inside you was meant to help you at some point. And so if you can acknowledge that in the moment, but then also, obviously, maybe try to try to work on that later in some way, there are obviously many ways to kind of modalities, um, to kind of help overcome that. But, um, there's the idea of, uh, seeing therapies where there's the idea of thinking back to old memories and trying to rewrite update old memories and rethink. Uh, what was maybe the motivation of the sound? Maybe, um, your dad was making sounds in the car, was actually just tired or extra tired or something, or extra grumpy based on something that happened at work. And if you can put yourself back into that child sitting in the back seat back then and kind of rewrite that scene in your head. And it's very related to, I think, what I was just talking about. But it's very much, um, can kind of hopefully try to ease that inner child that's still warning you to this day.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yeah. Compassion towards that other person, too, to help diffuse the rage, really.

Adeel Ahmad: I think it's fascinating. Defusing a situation that happened 30, 40 years ago to kind of help you.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Well, it reminds me of trauma work, too, right. Part of trauma work is really sort of going back to that original situation that was so tragic or so horrifying, but helping to diffuse it now, because now you are safe. And maybe for decades, your body heard firecrackers and thought, I'm back in a war zone. Right. So we have to kind of rewire and rewrite and say, I am safe now, and I'm no longer back in that traumatic situation. Even though it sounds like by the sounds of those fireworks and sounds very similar in that way. There's so much here that I think really is deeper stuff. And I think that's the crucial stuff, because I can imagine so much judgment that people have, or especially before they know that this is a thing. What is wrong with me? I want to be a kind person, but my partner is driving me crazy when they just do something so innocent like snack on corn chips or whatever, it might be so confusing and and so, you know, being lost and I think you're creating such a good thing for people to be able to come and tell their stories and come together. I know some of my listeners, and and this is probably a preposterous question, but I have to ask it. What is a Misophonia conference? Like, uh, is everybody sort of able they're able to understand triggers? So, like, maybe we're not going to eat together. I'm not trying to be facetious, but I do kind of wonder, since everybody has these particular characteristics, how are those taken care of in a typical convention type of environment?

Adeel Ahmad: Yeah, no, that's a great question. Um, when we're all in the same room, it's very much like when you're around your brethren, it's almost like family, where I feel like we know that we're all at least trying, um, or we're sensitive to it. Or if somebody makes a sound that we know that we can just kind of look in their direction, they'll get it. That helps to kind of diffuse things. You're basically around other wounded people. So that, uh, aspect of it helps a little bit now. There are specific things the conference, when it's been in person, actually does, like at snack or breakfast, uh, it's all like things like, uh, soft foods, like hard boiled eggs. There's no crunchy things. Um, so they kind of take those steps, like soft muffins and whatnot. Obviously, you're not going to stand next to somebody who's maybe chewing those things, but at least there isn't, like, loud crunches, uh, for folks who are triggered, um, by those, uh, things. Other than that, uh, they always pick a, uh, location. Uh, I think it's like Embassy Suites, where there are like, two doors. Like, there's the front door, and then there's the door to the bedroom. So, like, when you're sleeping, you're always like, two doors away from, you know, the hallways and whatnot. So those Embassy Suites tend to be and it's not an ad for Embassy Suites, but they tend to be a little bit, uh, quieter. Um, and generally, a lot of us, honestly, I'll go and watch some lectures, uh, or, uh, sessions, but it tends to be the kind of the smaller group conversations outside that tend to be the most valuable. And there you can kind of find your own spot and whatnot you're around people who get you, and you get them even though you may have just met. And so it's fine. It's actually great. I, uh, highly recommend these conferences. Over the last few years, it's been virtual, which is obviously that also has its pros and cons. But, yeah, in person, soft foods, quiet rooms, and, um, the ability to kind of move around, uh, which is well.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: It speaks, too, to what you were saying before in terms of just knowing that someone is trying and knowing that you have some safety in the sense that the person is aware and it has your best interest at heart. You talked about that in the context of that being helpful in terms of family members. But it also speaks to just how you said automatically at this conference, you know, you're more safe. Because you know that people really do have an understanding. And that's validating. And it means that it's not as threatening. It's not like, oh, here's this clueless person that's going to come in with a jawbreaker right next to my ear. It really feels more safe there. It's so powerful, right?

Adeel Ahmad: We've either been in situations or we've probably been in situations. So we kind of don't even bring it up anymore because we've been blown off, we've been irrelled, we've been mocked, um, because it sounds so stupid. It's just like, why are you so how could you be so annoyed at a sound? Because everyone grows up thinking about the nails on a chalkboard. There's many things there's the manners aspect of it. There's a lot of things that we're told, yeah, you know, sounds are annoying and whatnot, but it's rare. Um, but this is a whole other level. So a lot of us are, um, there's that shame or guilt that has kind of like, layered on each on ourselves for so long that we don't even tend to bring it up with people. So if we can be around other people who at least understand, that's a huge deal because we're not used to that. We're used to being told that this is absolutely ridiculous and there's something wrong with you. Not only that, but you are making other people feel bad because, uh, it's your problem and you're blaming it on them when that's the last thing we're trying to do. Yeah, it just looks like it just looks like it.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Right. It's a gift to not have to explain and to not scrutinize about it. Yeah. As we wrap up, is there any particular research going on that seems to give you particular hope? Are there things in terms of interventions or things that are being assessed in the population? I mean, what is going on? Can we expect that maybe in a future generation, somebody might have an easier time dealing with this because of some of the places that the research has taken us?

Adeel Ahmad: Yeah, there's a lot of research now going on. Uh, but only really in the last few years, I think, has it really taken off because there's now the miscellaneous, uh, research fund. There is nonprofits@silkwat.org are providing grants, uh, to students. There's a lot of research going on. What I've been kind of I've just been particularly fascinated lately with this whole direction that we were talking about in terms of treating it as, uh, barring some, um, approaches from trauma work. Um, just that whole aside of it, the epigenetics, the potential that it's related to things that happened, uh, the wounded child that was wounded growing up, and that self compassion and rewriting. I don't know if you're rewriting your past, but kind of maybe using brain plasticity to kind of rewrite your responses to triggers now, which are now having the hindsight to realize that these are not threats anymore. Um, and so I think this is the direction updating your past to kind of help yourself in the present. I think it's a fascinating thing. It's not like we're going to be popping a pill or anything anytime soon to get over this. I think it's very much working, uh, on the brain and looking at yourself more holistically. It's not just a reaction in the present. It's a reaction that is an echo of something in the past. So I feel like that is, um, a direction that I think more people should look into as a way to treat this.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yeah. Is there anything about more conditioning or exposure types of things? Does anybody have help with sort of building, trying to desensitize?

Adeel Ahmad: Yeah, that's a good question. Yeah. Exposure therapy is, um, something that's a hot topic. I'll just say there are a lot of different approaches, and I feel like I've never heard of one that's helped everybody. I know that some people say certain types of exposure therapies help or at least conditioning, but I haven't really heard of that helping most people. And so that's not a direction that I necessarily go to as recommend as kind of like something to try right away. But lately I've been more interested in uh, self compassion and trying to repair whatever chronic trauma or low level small T trauma that may have affected you in the past. Now, I do think though, that I don't want to say they're necessary exposure or conditioning kind of therapies. But there are ways to maybe try to reframe your thinking of a sound uh, as it's happening. Like maybe try to think more about the reasoning behind the sound. Maybe try to think uh, sympathetically to the person making the sound. Like telling yourself maybe this person is chewing this way because they have some weird problem in their mouth or something. Now maybe you're creating a story in your head, but if that can maybe get you through a moment, then that's better than wanting to rip their head off. Or maybe there's an idea of if you hear a sound, maybe trying to manipulate it in your head, like maybe try to um think of using a remote control or something to kind of like make it go I don't know. I was just talking to a ah, therapist recently about and she's thinking about ways if you're listening to a sound trying to uh kind of like about control. It's about regaining control of the situation in your head. Trying to think that maybe you're the one manipulating the sound or at least you have some power over it. And that can kind of um it's definitely better than nothing and it can kind of maybe help you um, not be so angry about the sound. If you can feel like you're somehow in control of the sound when you obviously not actually in control of the sound. Um, maybe making in your head, making some jokes about the sound, maybe assigning a personality to the sound and just trying to uh, play with it. So those aren't necessarily exposure therapies, they're more about experiments with different strategies in redefining your relationship with that sound.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Yes. Oh my goodness. Well that is so connected to acceptance and commitment therapy in terms of redefining our relationship with negative thoughts. And some of those tools are very similar. The idea of taking our anxious thoughts and instead of running screaming from them, giving them a voice and disempowering the thought and turning them into a silly song or that threatening thought, we give kind of a farcical voice that kind of makes us laugh so that we're defusing from them, we're separating ourselves from them. And the other piece you mentioned that really resonated with me was this notion of um there is research that says that when we can have compassionate thoughts towards others, it does lower our threat response. So we're driving and somebody cuts us off and we feel threatened in that moment. Oh my goodness. But if instead we can reframe it, I wonder if that person's just gotten terrible news about a loved one and they're trying to get home quickly. It actually makes us feel not just more warm and fuzzy, but in a very visceral, physical way. It makes us feel less threatened. And I think that kind of work. We're just starting to scratch the surface, and it all seems so connected. This has been such a fascinating conversation, and I know, unfortunately yeah, likewise.

Adeel Ahmad: It's been interesting to hear your insights as well, uh, especially from someone who's obviously knows a lot about, uh, many different kinds of psychologists. Some of the stuff you said, um, yeah, it's been definitely learned a lot here. It's been really interesting to kind of hear my, um, random layperson, uh, ideas kind of, um, echoed, uh, back in a much more scientific, uh, way.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Well, they're certainly not random, and you're anything but a layperson at this point. You've done so much to help other people, and I really commend you for that. And I know that a lot of my listeners today will be interested in your podcast. So can you tell us again where to find it and what it's called and also the nonprofits that you mentioned?

Adeel Ahmad: Yeah. It's called the Miscellaneous Podcast. Pretty simple, you can find it anywhere you get podcast. I also have the site Misophoniapodcast.com, and you can reach out to me on misfunction podcast on Instagram and Facebook. Misfhonia Show on Twitter, uh, and email me. Hello@misophoniapodcast.com and yeah, I'm also on the board of a great nonprofit called So Quiet, headed, uh, up by Chris Edwards. And, um, Zach Rosenthal from, uh, Duke University is on the board as well. Uh, and we have a great advisory board as well. And So Quiet does a lot for advocacy, getting the word out for Misapplicia, and also providing now grants for research. So definitely, um, look at So Quiet if you're, um, a student looking to get some grants. Yeah, we're just getting started. So it's, uh, great to just kind of get more people who've been suffering in silence, at least aware of what's going on, and that kind of validation can go a long way.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Oh, that's so wonderful. Well, thank you again so much, Adil, for taking the time. It's really been a pleasure to talk with you. And I know a lot of my listeners have gotten a lot out of this.

Adeel Ahmad: Thank you, Andrea. This has been great.

Dr. Andrea Bonior: Thanks for joining me today. Once again, I'm Dr. Andrea Bonnier, and this has been baggage check. With new episodes every Tuesday and Friday. Join us on Instagram at Baggage Check Podcast. Give us your take and opinions on topics and guests. And you know, you've got that friend who listens to like, 17 podcasts. We'd love it if you told them where to find us. Our original music is by Jordan Cooper, cover art by Daniel Merity and my studio security, it's Buster the dog. Until next time, take good care.